My name is Seamus, but I don't celebrate St. Patrick's Day. That may sound incongruous for a dual citizen of the U.S. and Ireland whose grandfather founded the Irish American Cultural Institute. But on March 17 each year I actively avoid the leprechauns and the "Kiss Me I'm Irish" t-shirts and the silly green hats and the 9 a.m. Guinness guzzling. That's not because I'm opposed to having a good time and it's certainly not because I'm not proud of my Irish heritage. Quite the opposite: I'm worried St. Patrick's Day has become a farce, a celebration of cartoonish symbols of Irish culture that minimize, dilute and demean what it means to be Irish. Wrapped in an excuse to drink debaucherously (itself a stereotype long used to keep Irish immigrants down), the holiday is so devoid of culture that it may as well be grouped with fake holidays like SantaCon -- just switch red garb for green.

Certainly, the 34 million Americans with claims to Irish ancestry would agree that Irishness is more than green beer, shamrocks, and other images of the Stage Irish. You don't have to decipher the impossibly dense Ulysses by James Joyce (I haven't) to recognize that the richness of Irish culture is lacking in the drunken celebrations on St. Paddy's Day. I'm talking about music by the Chieftains and Van Morrison and U2, I'm talking about Beckett's Waiting for Godot, I'm talking about the teachers of the Irish language, I'm talking about the revolutionary Michael Collins, and I'm talking about Jonathan Swift and Oscar Wilde and Seamus Heaney (good name!).

When you see revelers stumbling in U.S. cities today, you have to ask, which Ireland are they celebrating?

In fact, St. Patrick's Day as we know it is really an American invention. Here are a few facts about the history of St. Patrick's Day that might surprise you:

- Until the 1970s, St. Patrick's Day in Ireland was a minor religious holiday.

As a kid, I already had an aversion to St. Patrick's Day. I never wore a green shirt to school on the holiday, a protest that without fail elicited pinches from my classmates -- and even confusion from my teachers. "But your name is Seamus," they'd say, dumbfounded, thinking I'd forgotten the day.

Like a lot of Irish Americans, my name offered the first lesson about my heritage. When your name is frequently mispronounced, you have little choice but to find out where it comes from. (See-mus? Shah-mus? Shameless?) My sister's name is Cáitrín (mind the accents!). That sparked our curiosity about our origins, notwithstanding the occasional butchered pronunciation over the loudspeaker at roll call.

My cultural education in Irish-American-ness came primarily from my parents and grandparents. That meant reading Irish literature from a young age. It meant pulling a Michael Collins biography down from the shelf and peppering my dad with questions about the Easter Rising. Why was the country divided by North and South? I learned that Ireland's flag, which flies outside of bars on March 17 -- the one with white between the orange and green -- was really a statement about peace between the two sides.

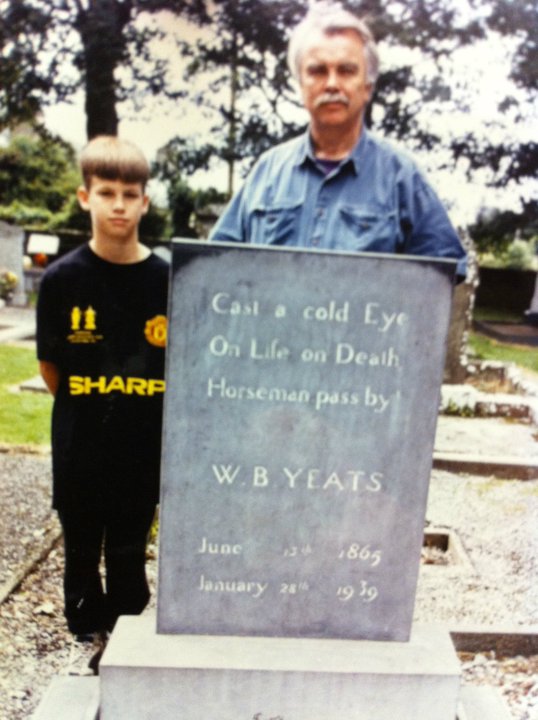

It meant family trips were often occasions for lessons about Irish history or current events or folklore, like the story of the famous one-eyed giant who roamed Tory Island. (I think I still believed that one after I knew the Santa Claus ruse was up.) It meant learning to play the violin and veering away from the Suzuki method to the jigs and reels. It meant studying for a summer at a school in County Donegal in a Gaeltacht, a region where the predominant language is Irish. It meant being asked to memorize William Butler Yeats' poem "Easter 1916" for a high school English class. The Irish struggle for independence Yeats writes about felt like distant past -- it was harrowing to find out that it wasn't so long ago. "Too long a sacrifice/Can make a stone of a heart," I remember reciting.

And it meant looking up to my grandfather, Eoin McKiernan, the father of nine kids (Deirdre, Brendan, Fergus, Ethna, Gillisa, Grania, Nuala, Liadan and my father, Kevin). My grandfather, a scholar who was named one of America's greatest Irish Americans of the 20th century, made it his life's work to teach Irish Americans about where they came from. To do this, he founded the Irish American Cultural Institute, which awarded grants to Irish writers, composers, artists, and Irish-language initiatives, including historical tours to the Emerald Isle and Irish language classes. (In fact, I recently learned that long before Seamus Heaney was a Nobel laureate, my grandfather gave him a writer's grant.) He was recognized internationally for his work and invited to the White House on several occasions. Princess Grace of Monaco chaired his Institute.

Forgive the family stuff, which can be boring. But I mention it because St. Patrick's Day is upon us. Today the river in Chicago is dyed green, parades are planned across the country, and people are ready to party. But when I walk around today, I won't be seeing the fullness of my heritage on display. I'm trying to keep in mind what Yeats, arguably the greatest poet in the 20th century, wrote about a sense of solidarity "wherever green is worn." I don't think he meant the annual buffoonery in sports bars in midtown Manhattan that passes for being Irish. He was talking about the deep identity that unites a people.

Figuring out who I am is a work in progress, but I think my grandfather, whom everyone called Grandpa Mór, would have understood. After all, he always said, "What is bred in the bone will out."

Seamus, age 10, and his father in Drumcliff, County Sligo, where W.B. Yeats is buried.