Public schools across the country are being gutted and shut down. Unsurprisingly, these closings are impacting vulnerable groups-- poor blacks and Latinos, special needs students and English language learners. This isn't new, but as self-proclaimed troublemaker Bruce A. Dixon noted earlier this year, much of this is happening on the "down-low." To be sure, communities are actively organizing and the stories are being covered locally. But there is a clear mismatch between the national coverage on this issue and its potential impact.

Most notably, schools are being shuttered in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington D.C. and Sacramento. I'll focus specifically on Chicago and Philadelphia for two reasons. First, these cities best exemplify the thorny issues that come with school closings--particularly for school staff and students. Second, there's personal interest here. I taught in a charter school in North Philadelphia. I've spent a quarter of my life in Chicago and worked in a variety of after school programs. Like people in those cities, and across the country, I am frustrated. However, I can't say I'm terribly shocked.

For those who are unfamiliar with the specifics, here is the deal. Chicago is undertaking one of the biggest school shutdown initiatives in American history and closing a whopping 49 schools, with about 800 teachers being laid off. Philadelphia is closing 23 schools and approximately 3700 school district employees will lose their jobs.

Lets put that in perspective, because people often don't know what these dry numbers look like or feel like. Chicago has experienced unacceptable levels of youth homicide in the past few years. This violence is in part a byproduct of misguided and sometimes vicious teens, gang/clique rivalries, hopelessness (rooted in socioeconomic inequality) and aimless shooters. With the closing of schools, minority students face the scary prospect of having to travel farther to school in a city that some residents provocatively refer to as "Chiraq." This prospect becomes scarier when one considers the 2009 murder of 16-year-old honors student Derrion Albert--an event that got the attention of the nation and President Obama. Albert was an innocent bystander who got caught in a violent conflict between rival gangs on his way home from school.

Nine-year old Asean Johnson gets it. The Chicago student-activist told a reporter "I think its pretty bad. They (Chicago Public Schools) do not like us. If they send us behind a gang territory where the kids don't like us, what do you think it's going to be? Violence or safety? They're saying they're trying to create safety for the kids, but you're just sending them in danger" (One notices the striking similarities between Johnson and Boondocks character Huey Freeman). This violence is so real that the city plans to pour millions of dollars into its "Safe Passage" program. Some are unsure if this will get the job done.

Philadelphia is closing half the number of schools as Chicago but is scheduled to lay off more than four times as many staff -- approximately 3700 people. The financial plan for the next school year, which some have referred to as "the doomsday budget," only includes funds for teachers and principals. No support staff across the city. Think about that. Guidance counselors to help kids with their college applications? Nope. Athletic, arts and music programs? Done for. New books? Please. The nurses that provide some semblance of medical information to kids who do not have adequate health insurance? Gone. Again, this is for the whole city. Some optimists believe that this is just a temporary situation for the summer to save money, and that funds will appear by the time the school year starts. Hopefully that is the case, but that still doesn't address the 3700 people who will be laid off for the summer and their families.

Much like Chicago, Philadelphians also have concerns that students will have to travel through rival neighborhoods and attend schools that were formerly rivals. But there are other concerns. It's so bad that School District of Philadelphia Superintendent William Hite simulated what the walk would be like for students who are going from one closed school to an existing school. Even Hite noticed the dangers posed to children by his 35-minute walk through boarded-up buildings, crackhouses and blocks with several registered sex-offenders.

The school administrations in both cities offer a grab bag of explanations. Their rationales typically cohere around underperforming schools, under-enrollment and underutilized facilities. In this line of thought, old buildings that have a capacity to educate 2000 kids but only enroll 500, 250 of which are graduating, are financially unsustainable. These justifications are accentuated by the undeniable existence of mediocre teachers, low expectations and mismanagement. Others see the rhetoric behind the school closings as smoke and mirrors.

Critics argue that school closings are not about achievement, but are essentially a game of musical chairs. They point to research that suggests that kids from closed schools end up going to schools that are not much better. More hardcore critics see school closings as a mere alley-oop pass to charter schools. These folks see school closings as part of a larger plan of privatization, gentrification and teacher union-busting.

These opponents call attention to research that highlights the mixed results of charter schools for student outcomes. They also argue charter schools intensify racial segregation and, through their selectivity discriminate against supposedly "undesirable" groups such as students with special needs and/or disciplinary problems. For these critics, lower rates of enrollment for students with disabilities, higher rates of expulsion in Philly, Chicago and Washington DC charter schools, and outlier schools like the Noble Street Charter School Network--which charge fines for student misbehavior-- tell part of the story.

In addition to taking it to the streets, activists are taking these educational issues to the courtroom. Lawsuits were filed in Sacramento (7 school closings) and Washington D.C. (15 school closings). These suits allege that shutdowns discriminate based on race and violate the Americans with Disabilities Act by disproportionately impacting students with disabilities (school closing critics lost in DC). In Chicago, several lawsuits have been filed that make the same allegations, while also claiming that the school district did not follow proper procedures in some of the school closings.

Others only see dollar signs like Rihanna. Philadelphia is cash-strapped and cites a $304 million deficit as a key factor for the closings. The state is exhibiting Mr. Scrooge-like stinginess and won't bail Philadelphia out. The state will, however, build a plush $400 million prison in a suburb just north of Philadelphia.

Chicago at least attempted to be slicker with its diversion of funds. The Windy City is using a program called tax increment financing that will seemingly funnel money from public schools to build an arena for a mediocre DePaul basketball team whose record the past few years is not much better than CPS'. (Shoutout to my DePaul homies though). These projects hauntingly confirm a vision that some adults and kids have--that prisons and sports are two of the few routes for poor minority youth. There is also the prospect of unnecessary premature black death, which is on display with the heartbreaking spectacle that is becoming the Trayvon Martin case.

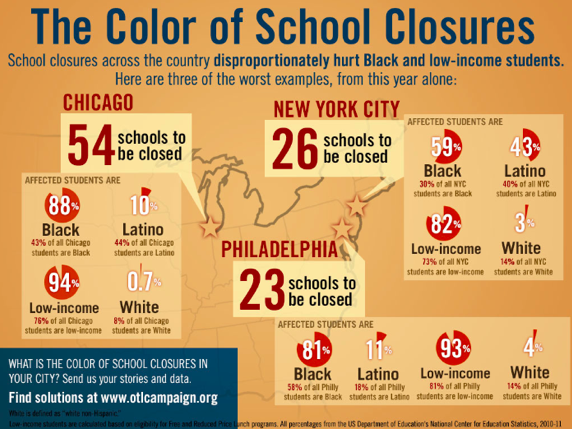

Whether it was part of some devious master plan or a strategy without strategists, the reality is this: in three of the top ten largest educational districts in the U.S., a slew of schools are closing. The graphic below, created by the National Opportunity to Learn Campaign, shows that unsurprisingly, these school closings are impacting poor youth of color. (Note: the list of closings in Chicago has decreased from 54 to 49). In many ways, the kinds of inequality Chicago and Philadelphia are witnessing are not new. What is missing from many of the commentaries on school closings is an ability to look backward at history and forward toward the future.

A seemingly undeniable historical reality is that minority youth have often been seen as devoid of the kind of innocence and worthiness of investment that white youth have been afforded. One could point to the intense criminalization of black youth that stretches back a century. Similarly salient is the Latino struggle for equal education that stretches just as long. Lets not forget the struggles around language rights that have impacted immigrant children. There is just a pesky persistence of discrimination against minority youth. The late Chuck Tilly might refer to it as "durable inequality."

Looking forward, let's make the assumption that public school closings will not disproportionately negatively impact black and Latino kids. They still have a bunch of obstacles to face, some of these include (and please don't hold your breath): inaccurate designations of disability; punitive schools; unaddressed sexual harassment of girls in schools and in their neighborhoods; the omnipresence of violent crime in their neighborhoods for both boys and girls, amongst others.

If they do make it past high school, they face: a Supreme Court that is seemingly licking its chops for the right case to get rid of affirmative action; ravenous for-profit universities that often leave individuals straddled with debt; a tight labor market that increasingly consists of low-wage, insecure jobs that have little to no benefits; and/or being forced to take jobs they simply don't want. As the hip-hop group Mobb Deep proclaimed two decades ago in their Darwinian song, "Survival of the Fittest," there's a war going on outside.

I've elaborated on some of these things elsewhere, but the bottom line is public education is being reengineered and social services are being cut. Now there is a labyrinth of options for us as a public. One could push the line of reimagining minority youth not as threats, but as worthy of investment. Another option is to insist on and contribute to more local level and national level organizing. Alternatively, one could take the reasonable perspective of parents (across racial and class groups) who are supportive of privatization, vouchers, and charter schools. These folks are not invested in this public/private divide in education and are more concerned with sending their kids to good and safe schools.

Citizens could also push against using business logic to educate kids and demand that corporate taxes reenter the discussion. (This becomes even clearer when one considers a film like We Are Not Broke, which shows how closing tax loopholes might address the fiscal crisis that allows public education to be perpetually on the chopping block). People could also simply not care, and look at this as an issue of other people's children.

Herein lies a small solution to a large-scale problem. My modest suggestion is that we think more critically about youth and work on not demonizing them. This comes with more substantive human contact with youth inside and outside of our neighborhoods and social networks. Irrespective of what happens and individuals' personal ideas, it's quite clear that the awkward transition from public to (pseudo) private education will require more meaningful volunteer work with youth. It's a simple act that does not require the kind of grassroots organizing that some people criticize or revere, but are unwilling to do.

We all have something to give, whether its advice, expertise, or time. Volunteer work may: help build relationships that might not typically occur (social capital); impart knowledge that some youth clearly aren't getting from their schools (human capital); and widen the cultural capital and repertoire of youth. Here's the grim reality: we reap what we sow. At the cross roads of politics and the economy, as it relates to youth, we are cultivating a group of people who may be en route to a land of further marginalization. Straight inequality, no chaser.

Volunteer work is not the sole solution. It is perhaps more politically safe than some would like (especially considering the pent-up frustrations with the recent Zimmerman acquittal), or might require more engagement than people would care for. But it is in volunteer work, where we can see the humanity and potential of youth, while extending to them a kind of compassion that they often don't receive from the major institutions in their lives.