A few days ago, economist Joseph Stiglitz said something quite provocative: "We've been shaping our society to create people who are more selfish."

The eye is drawn to the last part, "... create people who are more selfish." My takeaway message is at the beginning, "We've been shaping our society ... ."

In the same speech, he repeats a line from one of his books: "The reason the invisible hand was often invisible was that it wasn't there." He reminds us that, generally, markets do not solve our problems. "Nobody ever said that they were fair, that they would lead to a distribution of income that was socially acceptable." Markets fail, more often than we suppose.

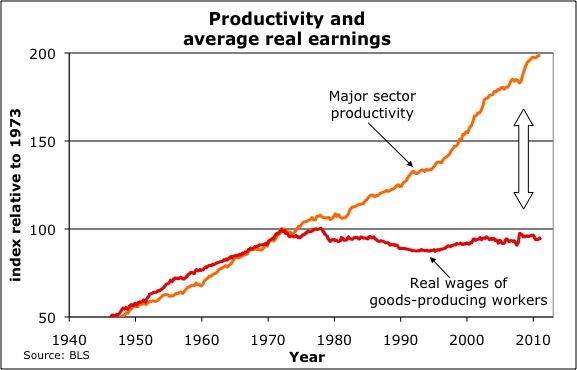

I first saw this remarkable figure in 2002:

In the post-war period, workers' wages increased in direct proportion to increases in productivity. Then, in the mid-'70s, wages abruptly decoupled from productivity.

The message of this figure is that wages, adjusted for inflation, would be twice what they are now, if workers had continued to share improvements in productivity. The top of our society has prospered, while more than 90 percent of us have stayed even or fallen behind.

This has consequences. As the economists say, "In the long run, consumption cannot increase faster than income." Income has been flat for the long run.

Let me give some examples of why this matters.

Erik Reinert wrote a terrific book, inspired by a question that troubled him as a Norwegian teenager on a class trip to Peru. Why does a barber in his native Norway make a comfortable middle-class living when an equally deserving barber in low-wage Peru makes so much less? The barbering profession had made only modest gains in productivity since the introduction of metal scissors in Roman times. The difference for barbers in Peru and Norway is the prosperity of their customers.

My father was a dentist in Michigan. Most of his patients worked in auto plants, where their union negotiated dental benefits. My father was a very adept businessman, compassionate to his patients, and he worked hard. He knew exactly what he had accomplished through his own work, and what had been given to him by circumstance. He had no doubt for one minute that the prosperity he enjoyed was directly connected to the next UAW contract with General Motors.

Nick Hanauer is a high-tech entrepreneur in the Seattle area. He says, as clearly as it can be said, that the magic of success in business is having prosperous customers who can buy your product. As an entrepreneur he did not create jobs. In his words, entrepreneurs want to create revenue with as few jobs as possible. Customers bring demand; demand causes businesses to hire. Prosperity comes from customers who can pay for your products.

We hear the legend of Henry Ford -- that he paid $5 per day to set a high wage standard in the community. Ford did well, not because he was generous and beneficent. In many ways, Henry Ford was a horrible, beastly man. He did well because customers in his community were prosperous enough to buy Ford cars.

Ross Perot may be a better example than Henry Ford. As an industrialist, Ross Perot knew exactly what NAFTA and other so-called Free Trade Agreements would do. As an industrialist he would be compelled by market forces to move production to Mexico, close facilities in the U.S., and reduce the wages paid to the workers in the community where he lived. As a patriot, he wanted trade policies that raised living standards, not lower them. He ran for president, at least in part, to thwart a flawed trade policy that would force him to hurt America.

The common theme is: "We all do better when we all do better."

Lately, the public mood has gone the opposite way. Simply put, we are told that we will all do better when most of us do worse. We demonize workers, and we imagine which of our neighbors should make additional sacrifice.

At the same time, top 1 percent executives believe they can move work offshore, lower wages, terminate pensions, shift health care costs, lay off workers and foreclose millions of homes. They don't accept responsibility for hurting America. They believe they can take a free shot, and the rest of society will pick up the slack.

Nobody is picking up the slack. That's a straight path to a Lesser America.

I recall the old Soviet joke, "My neighbor has a cow. I have none. I want his cow to die." Our version has become, "I have a cow. I'm okay if my neighbor never gets a cow. Nor wages to buy milk from my cow."

It makes much more sense to ask, "What works?" Even for those who look only to their self-interest, the long-term solution is to shape a society with prosperous customers. This is what Alexis de Tocqueville called "self-interest, properly understood."

Joseph Stiglitz warned that free trade and trickle-down policies are creating a distribution of income that is not socially acceptable. It won't work, and it has never worked, as Nick Hanauer says in his video interview.

Our past success was built, in part, on economic mobility, opportunity for anyone, and a strong middle class. Take that away, and we're just a large sluggish country with a lot of good memories and bad karma.

References: