The exhibition The Cult of Beauty, now in its only U.S. showing at The Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco (through June 17) reminded a friend of mine that, when she lived in New York City in the 1960s, "you could have bought most of these paintings for a song."

Not any more.

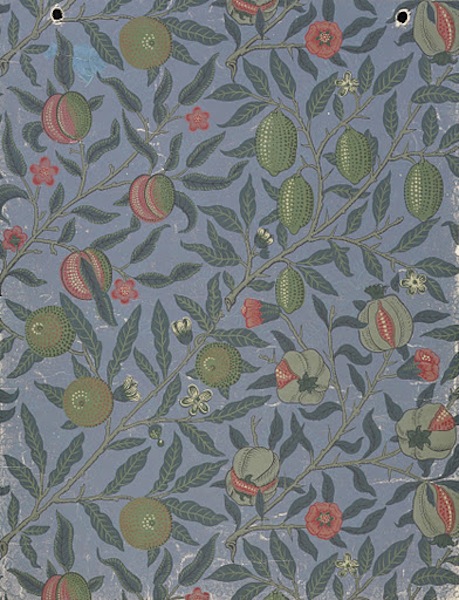

The exhibition celebrates the Victorian avant-garde of 1860 to 1900, and includes the work of such disparate artists as Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Aubrey Beardsley, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Julia Margaret Cameron, Kate Greenaway, William Morris and John Everett Millais, among many others. An explosion of interest in artisan craftsmanship as well as in the so-called fine arts took Britain over during these years. This exhibit shows how aesthetically far-reaching that interest was. Here you can see painting, printmaking, sculpture, furniture, silversmithing... even wallpaper! Although wallpaper designed by William Morris isn't your every day sort of thing.

William Morris & Phillip Webb, England, Pomegranate design wallpaper, 1865-6. Used courtesy of Victoria & Albert Images.

In the catalog for the show, produced in collaboration by The Victoria & Albert Museum of London and The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Stephen Calloway writes about the loathing among many artists for "the ugliness and increasingly vulgar materialism" that had been brought about in Britain by the Industrial Revolution. "One clear and revolutionary aim," he continues, "was to create a new ideal of beauty."

The high aesthetic grace that luxuriates in this exhibition was the result. Even with a chair, if it were designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, the experience of looking at it would probably be more satisfying than the experience of sitting in it.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Chair, ca.1884-6, mahogany, with cedar and ebony veneer, carving and inlay of several woods, ivory and abalone shell. Used courtesy of Victoria & Albert Images.

The tea served by your hostess from Christopher Dresser's pot would most certainly engender more conversation about the pot than it would about the tea.

Christopher Dresser, Tea Service Set (teapot, sugar bowl, milk jug), 1880. Silver plate with ebony handles. Used courtesy of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

It's quite true, though, that this era resulted in much kitsch. It was this that probably made the work seem so available to my friend in the 1960s. There is a fair amount of good, proper British Victorian comportment, particularly in those works that show classically dressed women in a state of dreamy innocence. John William Waterhouse's Saint Cecilia is one such.

John William Waterhouse, Saint Cecilia, 1895. Used courtesy of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The emotions in the painting are so lilting, fresh-faced and unconflicted as to be literally unbelievable. (In this era, there seemed to be many beautiful young women fainting quite a bit.) Nonetheless, the painting in Waterhouse's piece is so good that the viewer can be forgiven if he passes over the cliché and simply enjoys the extraordinary technique.

A painting like Edward Burne-Jones' Laus Veneris is similarly soporific in its tendency to chaste dreaming.

Edward Burne-Jones, Laus Veneris, 1873-8. Used courtesy of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

But it demands your attention, its extraordinarily complicated composition and the painting of the fabrics in the women's dresses... the painting of the women themselves... require several viewings just to take it all in. Even the sheet music is astounding. And, to Burne-Jones' credit, there are also the rambunctious knighted horsemen out the window enjoying the recital just as much as the virgins are.

Innocence was not the only thing depicted by these artists, though. Dante Gabriel Rosetti's The Daydream is formidably sensuous, showing a by-no-means classic beauty enjoying some sort of passionately tantalizing thought.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Day Dream, 1880. Used courtesy of Victoria & Albert Images.

The thought, I believe, comes not from the book on her knee, rather from the titillation of the palms of her hands by the rose in one, the branch of the flowering tree in the other. Her dress is so dark and many-layered with somber color that it seems to have come from the greenery that surrounds her. Fruitfulness flows from her body, expressed by that cloth, and even more so by her eyes, her lips and her sumptuous hair.

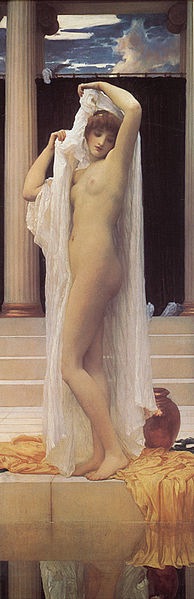

And, to be sure, there is Frederic Leighton's famous The Bath of Psyche. Innocence preparing itself for bathing. The waters will take her to the dream. The frock she removes is white and soft, a sweet comfort to her unmarred skin. She is too perfect an English girl, but she is nonetheless the essence of sensuality.

Frederic Leighton, The Bath of Psyche. Used courtesy of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Terence Clarke's story collection Little Bridget and The Flames of Hell was published earlier this year.