Nigeria is the greenest populous country in the world, but it is so entirely by accident. We fuel a population north of 170 million -- the seventh largest in the world -- on an available installed grid electricity generation capacity of fewer than 6GW.

In the context of Barack Obama's initiative last week with his inaugural Africa Leaders Summit and the lofty promises of the "Power Africa" initiative it seems worth pointing out that the problems with the development of Nigerian power generation and distribution are basic economics, and internal failures of local policy.

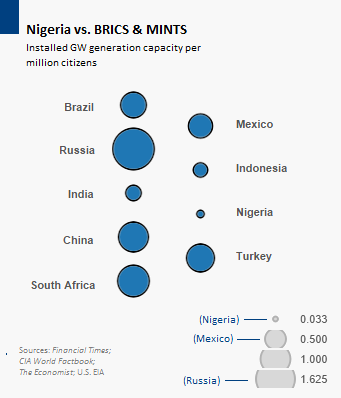

Not only does Nigeria lag massively behind the African average (shocking when you consider that Nigeria is Africa's largest economy by GDP) our grid capacity per capita rounds, on a one decimal point basis, to zero. In fact, the average Nigerian, who uses 136KWH per year, consumes just 3 percent of the power of the average South African, 5 percent of the average Chinese citizen and, under a quarter of the average Indian. We have an installed capacity that is a fraction of the per capita mean of the other "BRICS" and "MINT" countries that Nigeria loves to compare itself to.

Let it not be too bold to say that Nigeria is bad at generating and distributing electricity.

In Nigeria only one in four have access to the grid, and of those that do only a small minority have supplies of electricity for more than a few hours a day. "Epileptic" power outages are characteristic of a sector starved of investment: first as a state-owned monopoly and now, following privatization, from poorly conceived price controls and private regional distribution monopolies that have scared away necessary capital, impeded competition and discouraged new entrants to the market.

The government projects an increase in available installed grid capacity to 10GW by the end of 2014 -- already woefully inadequate in the context of present demand -- but this will doubtless be a dismal over-estimation. This lack of electricity is constraining our economy and inhibiting growth. It seems that Nigeria will continue to do the world's climate a favor for at least a decade to come.

In September 2013 President Goodluck Jonathan handed over control of 15 state-owned electricity companies to new private owners. It was hoped that the move would encourage essential investment, but in reality it has been a fiasco.

The newly established Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading plc (NBET) is now the sole purchaser of power from the national grid. It would seem its only purpose is to obstruct development in the power sector. The NBET fixes the price at which power is sold and the internal rate of return (IRR) for power projects. As a result greenfield generation projects struggle to get off the ground as they battle through a regulatory nightmare, sometimes for many years, before construction can even begin.

If we baked bread like we generate power then we'd starve.

Think about it like this: at present a baker, confident that his bread will have to compete on price and quality, determines how and when he will set up a bakery based on his projection of supply, demand, his costs and his product's quality and differentiation. However if all the bread in the country was required to be bought by a government ministry through contracts negotiated before bakeries could even commence construction, and not through a flexible and responsive market exchange, it would not just have an effect on the sale of bread but on the rate at which bakeries were built.

After all, when the ministry determines what it will pay for bread based on assumptions on how much profit each particular baker will make, the wages the baker proposes to pay his workers, as well as the projected cost of flour and butter, until accord can be reached on these costs not a single foundation will be dug. As a result the population continues to suffer from limited supply and choice.

Further, in Nigeria there is a severe misunderstanding of the essential role that financiers play in development. No banks will let the developer of a power project draw down on the funds to start building until an iron-clad purchase arrangement is in place. Nor will a banker or financier give the gas producer a loan to develop gas fields or the downstream gas supplier capital to build additional pipelines in order to supply fuel to the prospective power plant until the banker is sure that the power plant is actually being built.

This means that in Nigeria the majority of electricity is generated by expensive small private diesel and petrol generators, and if a household cannot afford a generator they go without. Ironically then fixing the price and profitability of power does not just create shortfalls in supply but, in aggregate, results in some of the most expensive electricity in the world; which most Nigerian's can scarcely afford.

We ignore market forces at our peril. The only regulation in the power sector should be based on the interests of safety and protecting the environment. These are the only regulations we can afford.