The huge earthquake that hit Nepal on April 25, 2015 killed over 8,000 people and injured more than 23,000. An avalanche triggered by the quake swept through Everest Base Camp killing at least 19 climbers and staff, including my friend Dan Fredinburg. Rightfully so, given the scale of the tragedy across the country, the disaster brought a premature end to the climbing season on Mount Everest. This meant that for a second year running my Kenyan Everest Expedition failed in its mission to get Steve Obbayi to the summit of the world's highest mountain. It waits to be seen if there will be a third attempt.

The three years I worked on the project were a transformative time in my life, a chance to refine a vision for how I wanted to work and to gain some invaluable experience in what it takes to run an expedition. But they were brutally hard and I often questioned whether the effort was worth it.

Background to the Expedition: In 2007, I cofounded the children's home Flying Kites in Kenya, with the goal of creating an institution that would redefine how children who had had the worst start in life would have a real chance to fulfill their potential. I was fully involved for the first five years and enjoyed the on-the-ground hustle of buying land, building, adopting the children, staffing etc. However, as soon as that start-up phase was over I knew that my skills were not given to spending 11 months a year working in an office.

Photo: Sandy Nesbitt

At that point, I decided to pursue my own ambition to climb Everest. I discovered that Kenya had never made an attempt to climb Everest so decided that I would start the Kenyan Everest Expedition. I created it in its entirety, selected the climber, trained him and raised funds for a first attempt in 2014 and a second attempt this year.

The major lessons I learned were:

1) Make sure your story can be easily sold: if you can't easily raise funds then it risks not happening. Everest was a tough sell from the outset. Five hundred or so summits a year mean that it's unique value as a marketing tool is limited. Because of this I chose to focus my fundraising on the Kenyan sponsorship market, where the lure of supporting the first Kenyan climber to the summit was strong. The strategy worked, but with minimal margin for error.

2) Have a strong team behind the scene to raise funds, manage sponsors, do PR etc (to be honest this wasn't really a lesson; I knew this already but had no way to engage such a team because the Everest story was not strong enough.) I had some great help from two friends volunteering their time but was conscious of the burden it was placing on them.

3) Budget at least a 20% contingency. Things always cost more than you expect and there will always be unanticipated costs. Financial strain strips all enjoyment from any activity.

4) Make sure there is true synergy between expedition goals and expedition sponsors. Make sure those sponsors have the means - budget, knowledge and human resources - to properly leverage their sponsorship. Their amplification of the expedition mission is a critical part of ensuring massive message reach. Think of them as genuine partners, rather than paymasters.

Although it has been an experience which has had few enjoyable moments, ultimately the lessons learned were worth it, and are going to be so valuable for future expeditions. In Kenya, the expedition has certainly worked to create a platform to allow Steve to be an inspiration. It has had excellent press coverage and, despite two failed attempts, he returned to Kenya last month a national hero and a genuine inspiration.

Of all the great challenges in the world - and don't doubt that an attempt on Mount Everest remains one of the world's great challenges - I feel that a climb of Everest is the one that ought to be done as quietly and discreetly as possible. Disprove the critics' assertion that this climb is merely done to bolster the ego by cracking on with it without mentioning a word about your efforts. Unfortunately, I had set it up so that, to be considered a success, the expedition had to be broadcast as far as possible and as loudly as possible. It was a profoundly uncomfortable experience.

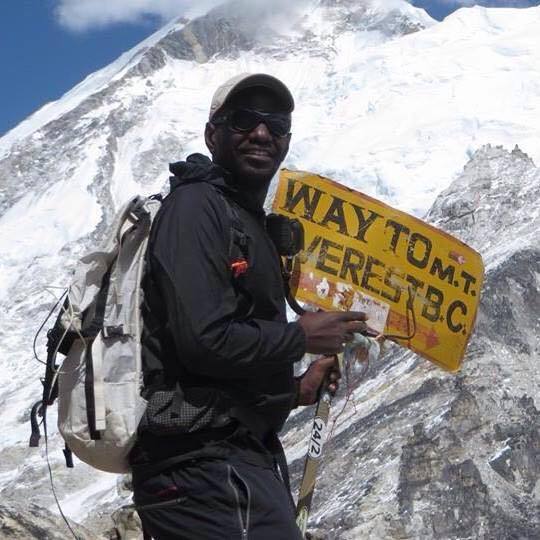

Steve approaching Everest Base Camp

Perhaps the greatest realization I have taken from the experience was that I can come to terms with having made bad decisions without that those decisions becoming manifested as regrets. Regrets are so incredibly draining, and they serve no purpose. Accept the mistake if a mistake was made, learn the lesson, and then move on.

There were many times over the last three years when I was a whisker away from giving up, the project has cost me a huge amount both financially and emotionally and in the end we did not even complete our mission. But, even with all that, I in no way regret making the decision to start. I wouldn't do it again, that's for sure, but I'm glad I did it the first time! Beyond the practical lessons outlined above I have recognized how hardship gives patina to your character: you become wiser, hardier...more human. And seeking to become more human cannot be a bad thing.