Last week, the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held hearings on Flint's water crisis. The committee heard testimony -- and plenty of finger pointing -- from leaders at all levels of government, including Michigan Governor Rick Snyder (R), who was repeatedly called on by members to resign.

At the heart of the hearings were two simple questions: how did this happen and who is to blame?

Over the last few months, growing outrage has thrust Flint's water crisis into the national spotlight, and into the ongoing presidential election. This was most apparent when earlier this month, CNN hosted its Democratic debate in Flint, giving impacted residents a chance to speak directly to the presidential hopefuls.

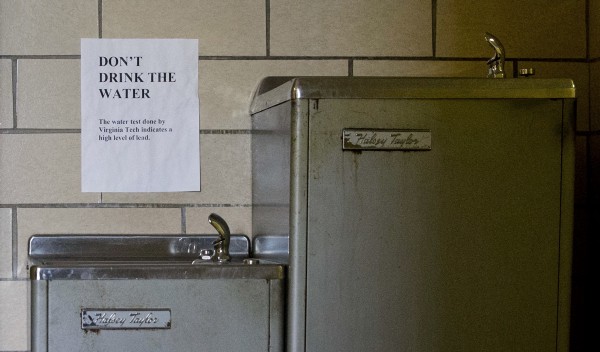

The opportunity to ask the first question, and therefore frame the debate, was given to Flint resident Mikki Wade, a mother of two, who described the daily challenges the water crisis has placed on her and her family. She lamented that "Once the pipes are replaced, I'm not so sure I would be comfortable ever drinking the water."

Then, Wade asked, "If elected president, what course will you take to regain my trust in the government?"

Considering the multiple levels of government failure -- from the emergency manager initiating the switch in the city's water supply to the governor's office not heeding residents' calls for help -- it's a fair question to ask those seeking the highest elected office in the land. Particularly, as they ask for votes from people who have every right to never trust the government again. And yet, the following week, the people of Flint turned out to the polls in record numbers to vote in the Michigan primary.

"All elections are important, but this one is very important. Look at [my grandchildren]. They're going to have to be watched for the rest of their lives because of what happened." -- Sharise Harris, Flint Resident

Flint's record turnout is not necessarily surprising. As County Clerk John Gleason explained, "People want to be heard. They are tired, and the city's water crisis is one reason they are showing up to vote." But with ongoing concerns about who is to blame and who can be trusted, it is certainly noteworthy.

Perhaps the real question is not whether the people of Flint can trust the government again, but which government they trust.

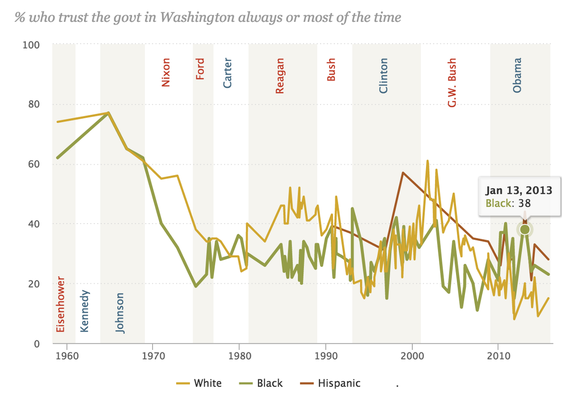

African Americans trust the federal government at higher rates

Once the booming Vehicle City where General Motors was born, Flint has since lost its industrial base. Subsequently, government investment in the city's schools, infrastructure, and workforce has also been in decline. Today, most of the city's residents live paycheck to paycheck, with more than 40 percent of residents living below the federal poverty level. Flint is also a largely African American city, composing 56 percent of the city's population -- significantly higher than the 13 percent African Americans represent in the general U.S. population.

"Despite the U.S.'s long history of discriminatory policies towards black citizens, black people often have higher trust in the federal government than white people."

While the state government failed Flint, many residents are looking towards federal leaders for answers. Last week, many Flint residents, including Nakiya Wakes, traveled to Washington, D.C. to attend the hearings on Capitol Hill. Wakes told the Detroit Free Press that she was grateful for lawmakers' "outrage on our behalf." It is not every day that people find comfort in Congress.

Despite the U.S.'s long history of discriminatory policies towards black citizens, black people often have higher trust in the federal government than white people. While trust in government is much lower today than it was 50 years ago, at the beginning of Obama's second term, trust among blacks was at 38 percent, compared to 20 percent for whites. Today, only 15 percent of white people feel they can always or mostly trust the government compared with 23 percent of blacks.

Source: Pew Research Center

Given the enduring effects of past discriminatory policies, such as segregation, underinvestment in black communities, and failings of the criminal justice system, such figures may be surprising. But as Dorian T. Warren, an associate professor of political science and public affairs at Columbia University, explained in a piece he wrote for The Nation:

What explains African-Americans' continued belief in the government despite its inconsistency -- at best -- in recognizing blacks as full citizens? The answer lies partly in the fact that despite a long history of exclusion and neglect, the federal government has provided the most mechanisms for protecting blacks from hostile state and local governments during the high moments of progressive reform -- from Reconstruction to the New Deal and Civil Rights movement, to the Great Society.

Despite the fact that government has taken actions that represent the worst of our country, it has also taken actions that represent the best. From the Civil Rights Act to voting rights to the legalization of same sex marriage, the federal government has often pushed progress when many states weren't "ready." It is not surprising, then, that black people are much more likely than other groups to believe that the federal government has an obligation to provide basic services and intervene in the country's major problems. And in the case of Flint, turn to the federal government for answers and help in their hour of need.

African Americans trust state and local government less than whites

Still, the situation in Flint is largely about what happened between state and local leaders. And when it comes to the question of government trust, trust has effectively been destroyed there.

Typically, all groups, regardless of background, tend to trust state and local governments more than the federal government. However, as political scientist Shayla Nunnally discusses in her book Trust in Black America: Race, Discrimination and Politics, "whites trust local government more than blacks do." In fact, black people are the least likely to trust their local governments compared to other groups. This makes sense, as discriminatory practices, such as land use decisions or policing tactics like "stop and frisk," are easily linked to local government actions.

In the wake of Flint, white people nationally are more likely than blacks or Hispanics to be "very confident" that their tap water is safe, while blacks are significantly more likely than whites to think it's a sign of a more widespread problem.

What makes the situation in Flint more complicated is Michigan's emergency manager system, and the lack of trust established from the start. Flint's water crisis -- and the deplorable school conditions in nearby Detroit -- has called into question the state's practice of appointing emergency managers to take control from local elected leaders in largely black jurisdictions. According to The New York Times, "Residents of majority-black cities have long cried foul over the practice. They argue that it disenfranchises voters and violates a deeply felt ethos of American democracy that allows for local representation."

Further, in the largely black cities of Flint and Detroit, the emergency manager system gives more decision-making power to the mostly white, Republican state government. The very aspects of local government that typically make the public trust it -- responsiveness and proximity to the people, residents' ability to hold elected officials accountable -- are completely undermined by emergency management. This sort of betrayal plays into the very anxieties that reduce black residents trust in local governments.

Why government at all levels still has a role to play in undoing damage it has inflicted

Typically, when the government fails to do its job, conservatives swoop in to espouse the values of the private sector. But the government has an obligation to undo the effects of past policies that contributed to these outcomes. And while government leaders are at the center of the current crisis, the challenges Flint has faced over the years stem from being abandoned by the private sector and government alike. The private sector is not a panacea for improving government functions.

As David Graham explained for The Atlantic, "Failures of government and the effective disenfranchisement of Flint voters produced the crisis and now private-sector philanthropy is jumping in to fill the gap. But that may introduce its own problems." Namely, the undemocratic nature of decision-making and lack of accountability, further disenfranchising the people of Flint. What Flint residents need now is a government of their will that is responsive and accountable to their needs.

The federal government is well-positioned to lead the way while state and local officials take the long and strenuous road toward restoring trust and addressing longterm needs. Unfortunately, Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) is blocking a $100 million federal funding package that could help Flint residents deal with the widespread contamination of the water supply. Flint needs resources and leadership, not politics.

"Flint needs resources and leadership, not politics."

And there are a number of actions Congress can take to increase funding for water infrastructure, improve testing and monitoring of lead, and reform regulatory oversight for all communities.

But most importantly, leaders must focus on the long-term impact on Flint's youngest and most vulnerable residents, whose future health and wellbeing have been compromised. As more funding is directed towards Flint, state and local leaders must ensure investments are made in early childhood services that support the full spectrum of physical, social-emotional, and educational needs of the city's children.

While trust may waver in government from time to time, polling consistently shows that people want government involvement in priority areas, such as healthcare, energy, poverty, and education. Together, these seemingly competing attitudes reveal that people don't want smaller government -- they want better government. It is this "better government" that has enabled African Americans to make strides in this country and trust government despite its past failings, and why a community like Flint can still call for government intervention in the face of betrayal.

Better government is possible when it isn't undermined. When people are able to freely select their leaders and hold them accountable. When programs are invested in and aren't prematurely ended.

Better government is what the people of Flint want and deserve.

This article originally appeared on the author's Medium page.