Part of the Food and Drug Administration's "Statement of FDA Mission" reads (emphasis mine):

FDA is also responsible for ... helping the public get the accurate, science-based information they need to use medicines and foods to maintain and improve their health.

Why, then, does FDA food labeling contain harmful omissions?

To reap the health benefits, I began eating canned sardines packed in olive oil years ago. I eat the contents of a single can nearly every day, but I recently discovered that the nutritional information I thought to be true wasn't accurate at all.

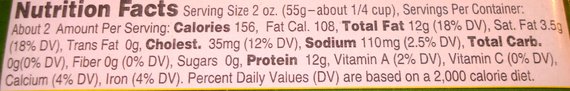

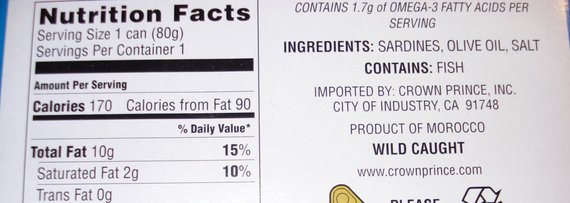

My husband picked up sardines at the store but bought sardines from the brand Season, not my usual brand, Crown Prince. Unfamiliar with Season, I compared the two brands' nutritional information. I was shocked to see that, while sardines from both the Season and the Crown Prince brands came in 3.75-ounce cans, containing 106 grams of ingredients (including wild-caught, skinless, boneless Moroccan fish in olive oil and salt -- virtually identical in all respects), the Season brand noted about 254 calories for the contents of the whole can, while Crown Prince's "1 can" serving was 170 calories.

When I contacted Crown Prince and expressed concern about the calorie difference, I was referred to the grams listed in the parentheses behind the words "Serving Size 1 can": 80 grams. But the front of the box states 106 grams. What happened to the other 26 grams?

It turns out that Crown Prince, with the FDA's blessing, had the sardines drained of the olive oil before the nutritional analysis was implemented.

I contacted the FDA for clarification, and Jennifer Dooren, Press Officer for the Office of Media Affairs and Office of External Affairs, provided me with the following information (emphasis mine):

According to the Code of Federal Regulations there's an exception for raw fish and a few other things packed in a liquid that's not customarily consumed:

(9) The declaration of nutrient and food component content shall be on the basis of food as packaged or purchased with the exception of raw fish covered under 101.42 (see 101.44), packaged single-ingredient products that consist of fish or game meat as provided for in paragraph (j)(11) of this section, and of foods that are packed or canned in water, brine, or oil but whose liquid packing medium is not customarily consumed (e.g., canned fish, maraschino cherries, pickled fruits, and pickled vegetables). Declaration of nutrient and food component content of raw fish shall follow the provisions in 101.45. Declaration of the nutrient and food component content of foods that are packed in liquid which is not customarily consumed shall be based on the drained solids.

I am mystified and disheartened that such a regulation exists.

For years I have been underestimating my caloric intake by about 85 calories per day. That's over 2,500 extra calories per month, and I had no idea. Yes, the "1 can" serving-size notation has the 80 grams mentioned in parentheses, but who would think to compare the grams listed on the front of the box with the grams listed on the back of the box when the serving size is stated as the whole can?

The assumption that consumers don't eat the oil the sardines are packed in is not realistic. If the packing liquid isn't relevant, then why pack sardines in a cornucopia of different liquids that provide different flavors? Mashing up the sardines along with whatever they are packed in (oil, mustard, marinara sauce, hot sauce, etc.) makes a great cracker or veggie spread, and manufacturers surely know this.

The regulation also permits manufacturers of pickles and canned fruits to omit the liquid from the nutritional equation. But there are untold numbers of recipes that call for using pickle juice or the juice from canned fruits. People do routinely use the liquids from canned foods, and the nutritional information for that liquid is important.

The obesity crisis in this country is significant, and per the FDA website, the agency agrees with that assessment, providing the following information (emphasis mine):

Rates of obesity, heart disease and stroke remain high. More is known about the relationship between nutrients and the risk of chronic diseases.

"Obesity, heart disease and other chronic diseases are leading public health problems," says Michael Landa, director of FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.

Thus, we are advised to read labels and make informed choices. But what if the truth of the labeling is in question? Crown Prince is doing nothing illegal, because the FDA has given them and other manufacturers the freedom to disregard actual calories and other nutritional information contained in that "1 can" serving. Allowing them to drain the liquid before nutritional analysis is one thing, but allowing them to do that without telling the consumer is unconscionable. If solid foods must be distinguished from the liquid, the label should have dual information: for the drained solids alone, and for the entire contents of the can. A second-best solution would be for the label to state, "NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION IS FOR "DRAINED SOLIDS" ONLY." That's not hard to say.

The FDA is currently redesigning nutrition labels. Some of the changes are more cosmetic than essential, and other changes are more valuable, like modernizing the serving sizes. But none of the changes address "secret" calories or undeclared and negative nutritional sabotages.

The FDA should not contribute to the already difficult challenge of monitoring the nutritional value of the foods we eat. Caveats, omissions, and little white lies simply derail our best intentions, and there are a significant number of caveats and exemptions listed in the FDA regulations.

If Crown Prince had listed the true calories and nutritional content for their "1 can" serving, I would have still purchased their sardines. I like Crown Prince products, and I appreciate the company's easy-to-use customer loyalty program. But the truth would have given me the opportunity to adjust my caloric intake accordingly. That's fair.

Instead, I feel duped -- by Crown Prince, by the FDA, and by the manufacturers who are likely pushing for less-than-truthful nutritional information. After all, selling lower-calorie foods is easier than selling higher-calorie foods, and selling foods with hidden dangers is easier than selling foods with exposed dangers. But such misdirection is unnecessary.

The Season-brand sardines didn't employ the "drained solids" loophole, and a representative of another brand of sardines, Wild Planet, confirmed that, unless the word "drained" appears on the nutritional box, their nutritional information covers everything in the can. Honesty can work, and there is good reason to abolish unnecessary and harmful caveats completely. How could the FDA not recognize that unknown calories, or hidden salts in the oil, or sugars in the fruit liquids, would contribute to the obesity and ill-health problems we face today?

How are we to trust food labels when there are exceptions to the rule? Already, we are forced to become detectives to find out if foods labeled as "zero trans fats" really have zero trans fats. Because the FDA permits foods with "less than .5 grams per serving" to be labeled as "0 trans fats," we must sleuth our way through the ingredients looking for partially hydrogenated oils to learn the truth.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) informs us:

Further reducing trans fat consumption by avoiding artificial trans fat could prevent 10,000-20,000 heart attacks and 3,000-7,000 coronary heart disease deaths each year in the U.S.

So if a label states "0 trans fats," but we discover partially hydrogenated oils in the ingredients, we can determine that if we eat three servings of that something, we are really getting as much as 1.5 grams of unwelcome trans fats, in spite of the label telling us that we are getting none. That's bad for anyone, but it's of special concern for anyone who has experienced gallstones.

And finding out if we are eating genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is virtually impossible, because the FDA has determined that consumers are not entitled to know if our foods have been bastardized.

Food labeling should be easy, straightforward and honest. The FDA should abolish "less than" rules. Zero should mean zero. If there could be 0.5 grams of trans fats per serving, the label should say exactly that: "Trans fats: Up to .5 g per serving." A "1 can" serving should include all the contents of that can, especially since the ingredients list confirms what is actually inside. And a company should never be permitted to list only nutritional information for "drained solids" unless "Nutritional Information Is for Drained Solids Only" is right on the label for the consumer to see.

We don't need "science-based information" to confirm that half-truths in labeling are harmful. And the FDA cannot purport to be concerned with the obesity challenge in this country while simultaneously contributing to the reason that it exists.

The FDA has a hard job to do, but that doesn't give the agency a pass to shortchange the public. It has a responsibility to afford the consumer the respect he or she deserves by investing in "the whole truth." And we, as consumers, should tolerate no less from an agency that declares in its mission statement that its goal is to help us "maintain and improve" our health.