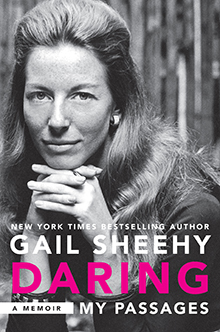

Gail Sheehy and I are contemporaries, almost exactly the same age. Her latest book, Daring: My Passages, is a memoir; so it is understandable why I was drawn to it. It turns out that we have a lot in common, undoubtedly due to the times we lived in. We both married young and got our PHT ("Putting Hubby Through" degrees; her husband was on his way to be a physician, mine on his way to be a professor. ) We both became young mothers and used writing as a way to earn money while we took care of our children. We were both swept up in the Women's Movement. She wrote about it and dared enter the male-dominated newsroom; I used it to justify my success writing for children and the empowerment it gave me while my mother looked at my newly-hatched raw ambition with horror and said, "You should have been a boy." We both became single mothers and took a risk to support ourselves and our families as freelancers. She could easily get work as a top magazine writer, I had no problem getting book contracts writing science books for kids. We both experienced white-knuckle months while unpaid bills piled up.

Of course, I had read her ground-breaking book Passages, which came out just as my first marriage was ending. It gave me courage and justification for the choices I was making. But the most absorbing thing about this new book is her writing. She has truly mastered the long form of story telling that was dubbed the "New Journalism" back in the 1970s. The intent of its creators was to tell a story in a way that was compelling and kept readers' attention. It was based on meticulous research -- hours of transcribed interviews and background reading -- composite characters, a narrative arc, telling details, and most importantly, the author's point of view. This was a huge departure from the style sheet of many newspapers that prohibited a reporter from using the perpendicular pronoun "I." Instead, if the reporter felt it was essential to the story to reveal oneself as an eyewitness, one had to use the third person as in "this reporter" or the ambiguous collective pronoun called the "editorial we." (I love to quote Mark Twain who said, "Only kings, presidents, editors, and people with tapeworms have the right to use the 'editorial we.'") The purpose of the newspaper style sheets was to distance the reader from the writer, to make the story more dispassionate and therefore more authoritative. The purpose of the new journalism was to make the reader care yet still adhering accurately to the facts.

In addition to the many parallels in our lives, my biggest takeaway from this book was Gail's discussion of her craft and the huge shout-out she gives to her many editors, most of all to her long-time love and husband, editor and publisher, Clay Felker. Clay founded New York Magazine and launched many of the new journalists. She described the questions Clay Felker empowered his staff to ask in creating the new journalism:

"Clay would send a writer off with several key questions: 'What are things the way they are? (Sniff out the latest trend); What led up to this? (Give us the historical background); How do things work? (Who is pulling the strings or making the magic or making fools of us?); How is the power game played in your corner of New York, or in the White House with a new president?' .......

He told writers, 'Take me inside the world you know, where readers don't have any access, and tell me a great story.'"

There is something about conflict with a great editor that elevates an author's craft. Like the creative process itself, it is a mysterious alchemy. The word "author" means "source," so I always figured it was part of my job to defend my work, to state why I wrote what I wrote. It is a part of the process of writing. I believe that the act of writing changes the writer -- I am not exactly the same person after I create a piece of work than I was before. I learn something new about myself while explaining something of the world so that children get it and that they care.

Gail Sheehy learned about toughness and perseverance by swimming competitively as a child. She ends her book with the mantra that has guided her life: "Lean forward, shoot off the edge of the pool, and keep on swimming." It is not so different from the mantra that has guided my life, which I attribute to Robert Anderson, playwright of "Tea and Sympathy" and "I Never Sang for My Father." In his less well-known novel, After, there was a female character who had a sampler embroidered on her wall. I adopted it for my life: "Expect nothing. Blame nobody. Do something."