If it seems that we have more big problems than we can solve these days, take heart. A small group of people can create a worldwide movement. It has happened before and it is happening again.

Take the case of Ellen Dorsey, the executive director of the Wallace Global Fund. More than 450 people gathered in Denver recently to help the Alliance for Sustainable Colorado recognize her as a "hero of sustainability".

Ellen is one of the founders of the divest/invest movement, which encourages colleges, municipalities, foundations and pension funds to sell their stocks in fossil energy companies and to reinvest them in solutions to global climate change.

As she tells it, the idea rose phoenix-like from two stunning defeats for advocates of climate action. The first was the international community's failure in 2009 to reach an agreement on cutting greenhouse gas emissions. That was the year it was supposed to happen in Copenhagen.

Then came Congress's defeat in 2010 of carbon cap-and-trade legislation. Foundations like the Wallace Global Fund had poured tens of millions of dollars into supporting the legislation and the Copenhagen conference, only to be outspent and outflanked by the fossil energy and climate-denial industries. "Four years ago we were all so very pessimistic," she says now. "Hopes for a solution to climate change were at a 20-year low; the economic and political challenge was just too daunting. It was at that moment of profound reassessment that the divestment movement began to grow."

The idea of making a moral statement with pension funds, endowments and philanthropic assets came up five years ago at a meeting where Ellen huddled with Alliance founder John Powers and investment experts Tom Van Dyck of RBC Wealth Management and Andy Behar of As You Sow. It didn't take long to find out that the idea had resonance.

"In early June 2011, five organizations and students from eight universities hammered out the first plan for a series of campus campaigns calling on universities to divest their endowments from coal. It launched the following August," Ellen says. "Some campuses tested a wider fossil fuel campaign, like the wonderful and courageous students at Swarthmore. Several campuses framed their campaign by calling for clean energy investments, to create their jobs, the jobs of the future. By the following spring, divestment campaigns had spread to dozens of campuses."

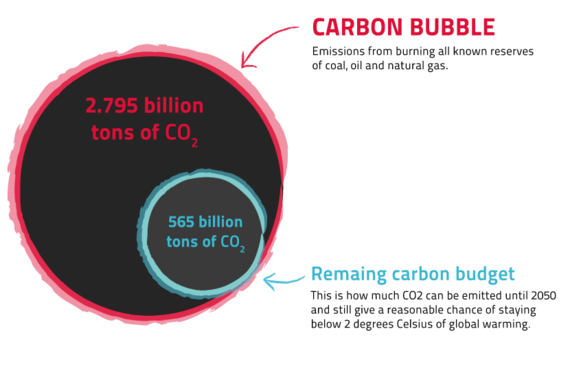

The same year, the Carbon Tracker Initiative (CTI), a non-profit think tank that "aligns capital market actions with climate reality", published a report that explained that human activity must keep atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide within a "carbon budget" to avoid catastrophic global warming. The global economy is close to exceeding that budget. To stay within it, most of the world's proven reserves of oil, coal and gas have to become "unburnable carbon".

CTI pointed out that this has major implications for the value of fossil energy companies and as a result, the global economy. Most of the value of fossil energy companies is in their underground assets.

In 2012, author and climate activist Bill McKibben explained this "terrifying new math" in Rolling Stone magazine. In clear prose and hard numbers, he noted that atmospheric warming must be held to no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels; that the world would exceed 2 degrees if it put more than 565 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere; that proven fossil fuel reserves contain nearly 2,800 gigatons of carbon; and that therefore, up to 80% of the reserves will have to remain unburned. McKibben reported that the unusable reserves were valued at $20 trillion, as though the carbon budget did not exist. Because of the risk of restrictions on carbon emissions, the reserves are greatly overvalued, creating a "carbon bubble" not unlike the credit bubble that burst around 2008 and resulted in the global economic recession whose consequences are still felt today.

The risk of a carbon bubble was confirmed in 2014 by former Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, a Republican, in a column he wrote for the New York Times. "We're staring down a climate bubble that poses enormous risks to both our environment and economy," he wrote. "Each of us must recognize that the risks are personal. We've seen and felt the costs of underestimating the financial bubble. Let's not ignore the climate bubble." In a speech later that year, he said, ""I am looking at this through the lens of risk - climate change is not only a risk to the environment but it is the single biggest risk that exists to the economy today."

Experts ranging from the International Energy Agency to the World Bank have since echoed Paulson's warning.

Meantime, from her position at the Wallace Global Fund, Ellen Dorsey provided resources to keep the divest/invest momentum building. She rallied other foundations - 90 to date - to sign up. Today, more than 1,500 institutions and individuals who represent more than $60 billion in assets have pledged to pull all or part of their money from fossil energy companies. Institutions representing an additional $100 billion in assets have committed to divest from coal.

In addition to McKibben and 350.org, a grassroots climate action organization that has spread to more than 188 countries, Ellen singles out the work of Mark Campanele of the Carbon Tracker Initiative. "I believe CTI will go down in history as unleashing the single most disruptive concept that changed the debate on climate change," she says.

"At critical points in human history, profound change is required," she said in her speech at the Alliance's hero event. "This is our underground railroad moment, where people of courage and conviction stand up and take action, where individuals are all-in, knitting together a beautiful quilt of advocacy, reinforcing each other's efforts and building power for change."

While the divest/invest movement reminds us that where we put our money is an ethical as well as financial decision, acknowledging the ethical and moral dimensions of climate change is not new. In 1992 for example, 1,700 of the world's scientists including most of the Nobel laureates in the sciences appealed to society to wake up to global warming.

"A new ethic is required," they wrote, "a new attitude towards discharging our responsibility for caring for ourselves and for the earth...This ethic must motivate a great movement, convincing reluctant leaders and reluctant governments and reluctant peoples themselves to effect the needed change."

The moral imperative of carbon reduction has led a variety of faith-based organizations to become advocates of climate action. Pope Francis will issue the Catholic Church's first encyclical on global warming this summer; he will address Congress and the United Nations later this year. The lay public in the United States also acknowledges the obligation to confront climate change. A poll in February by Reuters/IPSOS found that 66% of respondents feel that governments are obligated to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; 72% feel a personal responsibility to reduce their carbon footprints.

"When climate change is viewed through a moral lens, it has broader appeal," Eric Sapp of the American Values Network told Climate Wire. "The climate debate can be very intellectual at times, all about economic systems and science we don't understand. This makes it about us, our neighbors and about doing the right thing."

The leaders of the divest/invest movement believe the right thing as well as the smart thing is to pull our money out of industries that are as indifferent as sociopaths to the irreparable harm their products are inflicting on everyone else on the planet, present and future.

Some observers doubt that divestment will have a decisive financial impact on the huge fossil energy sector, but that is not the point. The movement gives everyone with a retirement account, every university with an endowment and every philanthropy with assets the opportunity take material action against companies that put short-term profits ahead of people and the planet.

The Alliance event was a moment to celebrate the progress the divest/invest movement has made so far, as well as the power of dedicated individuals to make a difference. Yet everyone involved in the movement knows it has a long way to go. Too many of us are still invested in fossil fuels. As Ellen Dorsey puts it, "If you own fossil fuels, you own climate change."

Graphic by the Carbon Tracker Initiative. Dr. Dorsey's speech is available on YouTube. The DivestInvest website offers instructions on personal and institutional divestment and reinvestment.