One of the most important elections of the decade will take place next month -- and most Americans don't know it. In fact, even many American political junkies who could pontificate as to which U.S. Senate seats will be toss-ups in 2016 or which members of Congress are the most vulnerable probably haven't yet focused on the fascinating dynamic shaping up on the other side of the Atlantic.

In case you're starting from scratch...British Prime Minister David Cameron, of the Conservative Party, is engaged, in what polls suggest is, a true toss-up as he seeks a second term and attempts to hold off hard-charging Labour leader Ed Miliband. As the May 7th U.K. parliamentary elections approach, below are 10 things that any self-respecting U.S. political junkie should know about the campaign to determine who will lead Britain for the next several years.

1) The Two Contenders

To those just plugging into British politics, U.K. governments are always led by either the Conservative (center-right) or Labour (center-left) parties. Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron was elected in 2010 after 13 years of Labour control and is now seeking a second term. As Tony Blair brought a more moderate "new labour" government to power after the party had been on the outs during the Margaret Thatcher/John Major era, Cameron has attempted to rebrand the Conservatives (also known as Tories) as less dour and more contemporary -- including adopting more conventionally liberal positions (at least in the American sense) on issues like marriage equality and climate change.

However, the emergence of the anti-European Union and anti-immigration party UKIP (think British tea party) over the last few years has made it more difficult for Cameron's 'modernising agenda' to take root. Faced with the rise of UKIP, Cameron has tacked right on issues such as welfare and Britain's role within Europe.

Ed Miliband emerged as Labour leader in 2010 -- a fresh face, taking over from Tony Blair and Gordon Brown who dominated the Labour Party of the late 1990s and 2000s. Miliband is closer to the party's traditional socialist roots than his immediate predecessors and has been openly critical of Labour's handling last decade of the Iraq War, bank deregulation, and a lack of commitment to addressing income inequality. He's considered to have done an effective job uniting the English left but his leadership has been dogged by claims from some that he is 'not up to the job'.

In fact, much of the Conservative campaign is based around attacking Miliband for this very reason - and polling even shows some Labour voters think of Cameron as a stronger and more effective leader. Further, the rise of the Scottish National Partly (SNP) means that Labour risks losing several seats to the Scottish Nationalists, threatening Labour's chances of being the largest party in parliament after the election.

One of these two men will almost certainly be the next British Prime Minister -- and given their respective challenges it is perhaps no surprise that...

2) It's pretty damn close!

Most of the polling over the past several months has shown roughly equal amounts of likely voters favoring the incumbent Conservative Party as prefer Labour. Unlike the election of the U.S. President, Brits don't vote for their Prime Minister. Instead, the Prime Minister is selected by members of Parliament elected in smaller legislative districts (similar to the election of a U.S. Speaker of the House).

The party leader that can command the support of the majority of the UK's 650 members of parliament becomes Prime Minister. For that reason, the magic number to make a Prime Minister is to secure the support of 326 members of parliament.

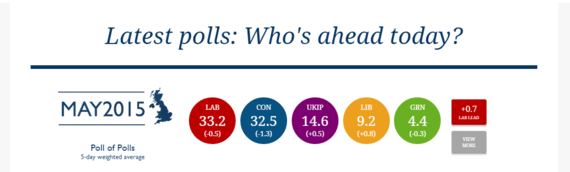

While this process makes national level polling less meaningful than it would be in predicting the popular vote for President in the U.S., these national measures are traditionally important barometers of which party is best positioned to win the most parliamentary seats. The most recent aggregation of polling shows the Tories and Labour taking an almost identical share of the vote.

Source: http://may2015.com/

Either Cameron or Miliband will almost certainly be Prime Minister following the May 7th elections -- both have a path to victory. It's very plausible that David Cameron could win and cement his role as a transformational figure in British politics OR that Ed Miliband emerges victorious and Labour is back in charge and will have dominated the British political process for most of the last quarter-century.

3) The party that gets the most votes or wins the most seats on Election Day might NOT elect the Prime Minister

The U.K.'s parliamentary system and multi-party dynamics make it very possible (indeed even likely) that neither the Conservatives nor Labour will win a majority of the country's 650 seats in the House of Commons. In fact, that's exactly what happened after the 2010 elections. In the previous election, Conservatives won the most seats but fell short of an outright majority. For only the second time since WWII, a coalition government was necessary to help form a working government. Five years ago, the smaller, center/center-left Liberal Democratic Party supplied the additional votes necessary to make Cameron the first Tory Prime Minister since the mid-90s.

Since this governing coalition formed in 2010, the U.K.'s party politics have become even more fractious. The Liberal Democrats, who had been the county's most successful smaller party over the last few decades, have not fared particularly well since they partnered with the Conservatives. The Lib Dems achieved 23% of the vote in 2010 but now poll in the single digits. The erosion in their support can be at least partially attributed to their role in increased student tuition fees, despite explicitly promising to oppose such increases in the 2010 campaign.

The Liberal Democrats remain potential coalition partners for Cameron (and to a lesser extent a Labour government), but it appears they will find themselves in a weaker position than they did immediately after the 2010 vote. In fact, they may no longer be the third biggest party in parliament after this election and will likely not have enough seats to deliver a coalition themselves.

As the Liberal Democrats have bled support over the past few years, two other parties have emerged as real factors heading into the 2015 elections.

UKIP

Led by the charismatic Nigel Farage, UKIP is to the right of the Conservatives and seems to have benefitted from increased Euro-skepticism generally and anxiety over immigration specifically. An invigorated UKIP will likely take some right-leaning voters from the Tories and could emerge victorious in a few seats traditionally dominated by Conservatives. The main concern for the Conservatives is that UKIP will take Conservative votes in a handful of swing districts, playing the role of spoiler, delivering these seats to the Labour candidate, and making a Labour government more likely. In some ways, the UKIP would seem a natural ally for the larger Conservative Party, but leading Tories have publicly ruled out a Tory-UKIP coalition. In the longer term, there is evidence that UKIP are a significant threat to Labour in traditional Northern heartlands that are anti-Tory but not particularly left-wing. However, for this election the threat is more acute to the Conservatives.

SNP

While the Conservatives warily eye the emergence of an ideological threat on the right, Labour has to be concerned about the rise of the Scottish National Party (SNP) in traditionally-Labour dominated Scotland. Fueled largely by the ill-fated 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum, the left-wing SNP (a pro-Independence Party) looks likely to be a dramatically more significant factor in the 2015 elections than in past campaigns. Estimates have the SNP taking 35-50 of the 59 seats in Scotland, most coming at the expense of Labour (who currently hold 41). To put this in context, the most seats the SNP have ever held is 11. A post-election Labour-SNP coalition has been ruled out by both sides but a more informal relationship is possible. SNP leader Nicola Sturgeon has ruled out any deal (formal or informal) with the Conservatives.

The extremely tight polling, combined with the rise of ideological and regional smaller parties, offers myriad possibilities if no party wins a majority of seats - and makes predicting what will happen in such a hung parliament very difficult.

Therefore, it is entirely possible (and constitutionally legitimate) that the largest party in parliament will not be able to form a government and that the second biggest party will form a governing coalition. For example, Labour might come second in terms of seats but form a government of some kind with the SNP and Liberal Democrats.

4)The fundamental economic argument in UK politics is reminiscent of the U.S. Presidential race in 2012...and may foreshadow the 2016 contest

There are a great many parallels between the British and American economies in recent years - and in how political leaders in both countries have sought to portray their respective countries' economic outlook. Like the U.S., Great Britain was hard hit by the global recession. As the U.S. economic recession helped propel Barack Obama's 2008 campaign, the slowdown in the British economy aided David Cameron's rise to power.

Much of the 2012 Obama / Romney campaign hinged on the questions of how quickly the U.S. economy was improving and which candidate voters would trust to make the economy work for the middle class. Similarly, one of the dominant narratives in the UK is Cameron's claim that the country's economic growth is exceeding expectations after inheriting a disaster from Labour. As one might expect, Ed Miliband's perspective is different. Miliband and Labour contend the Tories are looking out for only the very wealthy and that the economy has not gotten better for most Brits. Another reason some of the rhetoric might seem familiar is that Obama campaign veterans David Axelrod and Jim Messina have been advising Labour and the Tories, respectively.

The leader whose economic vision better connects with British voters will certainly have a critical advantage. Presumably, David Cameron's operation looked to the Obama 2012 campaign to try to replicate its success in winning (or at least neutralizing) the economic issue and targeting an opposition leader on which the public is not sold. Similarly, depending on the results of the 2015 UK election, there are very likely lessons to be learned by the 2016 U.S. Presidential candidates of how to connect with an electorate that still feels a real economic anxiety.

As might be expected in a close race such as this one, the polling on this subject is ambiguous. The Conservatives tend to lead on 'managing the economy' or 'economic competence' but Labour are more likely to have the advantage on 'making my family better off'. How UK voters square these somewhat conflicting views before they reach the voting booth will likely be crucial to the eventual outcome.

5)But it's not just about the economy

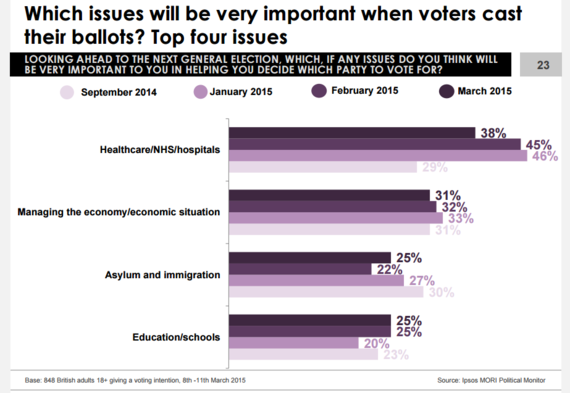

In recent opinion polls healthcare has risen to the top of the list of voter concerns, especially among women. The National Health Service, or NHS, (Britain's state funded healthcare system) is now often cited as the most important issue by voters while immigration is also high on the voter priority list. Labour tend to outpoll the Conservatives on the NHS whereas UKIP tend to be most trusted on immigration.

Another trend in the UK that may be recognized by Americans is the tendency of voters to distrust 'politics as usual'. In a similar fashion to how some US politicians run against 'Washington' it is common now for politicians in the UK, especially those in UKIP and the SNP, to run against 'Westminster'. Nigel Farage, UKIP leader and regular on Hannity, never misses an opportunity to criticize other parties as part of the 'same Westminster elite' while also playing to the hardcore right-wing base on hot-button issues of immigration and "Islamic extremism".

6)Britain's future involvement in the EU could hinge on this election

There are many voices in Great Britain - which has long had a unique relationship to the European continent - who advocate withdrawing from the rest of Europe. The emergence of the UKIP over the last few years is at least partially due to a rising Euro-skepticism in some corners of Britain. In many ways, the success of the UKIP will be viewed as a barometer of anti-European sentiment within Great Britain. Perhaps foreshadowing success in the upcoming election, UKIP actually won the UK nationwide elections to the European Parliament last June.

For his part, David Cameron has proposed a referendum on Britain's membership in the EU following a period of renegotiation of the terms of Britain's membership. Cameron's policy on Europe is potentially crucial to the UK election. Though he has promised a referendum in a second term, he could struggle to get it through a Parliament without a Tory majority. Should Cameron 'win' in May but fail to secure a referendum shortly thereafter, his new government could fall (necessitating a new election) before it has even started.

Conversely, Labor's Ed Miliband is a staunch advocate of the EU and says he'd oppose such a referendum. In recent days, former Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair has backed Ed Miliband's stance of not offering a Referendum. Blair argues that Cameron does not truly believe in one and is merely bowing to pressure from the right of his Party and that any vote is against Britain's economic and political interests.

In short, the 2015 elections are likely to have a major impact on Britain's role on the world stage - with potentially global strategic and economic implications.

7)Some Believe The Polls May be Skewed Against the Conservatives

In 2012, some American conservative pundits were quick to hop on the "skewed polls" bandwagon, criticizing pollsters and forecasters who predicted an Obama victory. While the self-proclaimed "un-skewers" were roundly embarrassed after the Obama victory, a somewhat more credible dynamic in the UK can offer similar hope to Conservative partisans.

In 1992, Conservative leader John Major over-performed pre-election polling that mostly predicted a Labour victory. Major ultimately won a relatively comfortable victory, giving birth to the "Shy Tory" explanation that Conservative voters were less likely to participate in opinion polls. British pollsters adjusted their methodology in the wake of the '92 elections, but some pundits believe the phenomenon continues and is inflating Labour support in opinion polls.

As with the "skewed polling" allegations in 2012 or earlier predictions of the "Bradley effect" in the 2008 U.S. election, not until the votes are counted on May 7th can it be determined if Tory voters are as "shy" in 2015 as they seemed in 1992. However, given the closeness of the race and the number of parties involved, pollsters in the UK face the biggest challenge in calling the election right since 1992.

8) Is Labour led by the Wrong Miliband?

Labour lead Ed Miliband may well be Britain's next Prime Minister, but there are at least a few who believe his older brother, David Miliband, is the more capable politician and would make the better Prime Minister.

Both Milibands were members of the Labour Party's governing cabinet in the Blair/Brown era, with David Miliband generally the higher-profile brother. David Miliband was a key ally of Tony Blair whereas Ed Miliband worked as an advisor to Gordon Brown for many years. When Labour entered the political wilderness after Cameron's 2010 win, the party had its most wide-open leadership contest since the early 90s. Among the numerous ambitious Labour pols who sought the party's top post were both Ed and David Miliband. While the Labour leadership selection process seems byzantine to those with American sensibilities, the Miliband brothers were the two candidates with the most support - with Ed Miliband besting his brother by about as narrow a margin as possible, largely as a consequence of support from British Trade Unions.

The brothers admitted the election was "difficult" and "bruising", and David Cameron has publicly said Ed Miliband "knifed" his brother in the back. After narrowly losing the leadership election, David Miliband left elected office and now heads the International Rescue Committee in New York City - and is still well enough thought of that Ed Miliband has to frequently answer questions as to whether his brother would have made the better Labour leader from journalists and voters.

9) Who is going to win?

It's going to be close. All we really know is that neither the Conservatives nor Labour will likely be able to win a majority and govern alone.

An important point for anyone watching the UK to understand is that it isn't just the relationship between Labour and Conservative that is important. What other parties do is important too. The UK's "First Past the Post" electoral system makes the relationship between votes and seats quite unpredictable. For example, if Labour and the Conservatives achieve the same vote share the likelihood is that Labour will win more seats due to the efficiency of their vote. Also, the Liberal Democrats could win 5 times as many seats in parliament than UKIP with fewer votes due to the geographical concentration of their vote. The SNP could win around 6% of the vote in the UK and win 50 seats (becoming the third biggest party in parliament in the process) due to the fact their vote is concentrated in Scotland.

Labour are slight favorites right now as they can win more seats than the Conservatives with the same vote share - plus the parties willing to deal with Labour in a hung parliament will almost certainly have more seats than the parties willing to strike a deal with the Conservatives. That said, David Cameron is a very skilled politician and out polls Miliband personally so Conservatives hope the race swings their way as polling day approaches - which is entirely possible. Projecting vote share to seats is a difficult business but a good rule of thumb is that until the Conservatives are at least three points ahead nationally then they will likely not have the requisite seats to form a government in May. In reality, the Conservatives probably need even a bit more of a lead than that.

In short....one mouth out from Election Day, it really is all up for grabs.

10) Where to get your UK Elections Fix

If you are interested in following the UK election more closely there are a number of outlets that are worth following:

Newspapers

Left: The Guardian

Right: The Telegraph

Independent (left leaning): The Independent

Polling/Analysis

May2015 election website

UK Polling Report

Political Betting

Polling Matters UK Podcast

Also keep an eye on the Polling Observatory's regularly-updated model, which is partnering with the Huffington Post, to forecast both national vote and seat-by-seat allocations.

Zac McCrary, a Democratic pollster, is a partner at Anzalone Liszt Research. On twitter, Zac can be found at @zacmccrary.

Keiran Pedley is an Associate Director and UK elections expert at GfK NOP and presenter of the podcast 'Polling Matters'. He tweets about politics and polling at @keiranpedley.