HBO aired a raw and riveting documentary last night: James Gandolfini's Alive Day Memories. A soldier's "Alive Day" refers to the day you didn't die — the day you narrowly escaped death, and, in the case of the ten young veterans profiled in the film, the day you start life all over, without a leg or an arm or a combination thereof, or your eyes, or your life the way it was and the way it was supposed to be. It is a powerful, horrifying, blunt film — there is no sugarcoating as Sgt. Bryan Anderson, 25, pulls up his shorts and wiggles the stump where his leg ends (a screengrab is here). Actually, that's legs — plus a hand and the feeling in three fingers on his other hand. Prior to the war, Anderson had been a gymnast.

HBO aired a raw and riveting documentary last night: James Gandolfini's Alive Day Memories. A soldier's "Alive Day" refers to the day you didn't die — the day you narrowly escaped death, and, in the case of the ten young veterans profiled in the film, the day you start life all over, without a leg or an arm or a combination thereof, or your eyes, or your life the way it was and the way it was supposed to be. It is a powerful, horrifying, blunt film — there is no sugarcoating as Sgt. Bryan Anderson, 25, pulls up his shorts and wiggles the stump where his leg ends (a screengrab is here). Actually, that's legs — plus a hand and the feeling in three fingers on his other hand. Prior to the war, Anderson had been a gymnast.

Prior to the war, Cpl. Michael Jernigan, 28, had been married. But then he lost his eyes in an explosion, and he came home and his marriage fell apart under the strain. Now he wears the diamonds from his wedding band in his prosthetic eye (the left one; the right socket is empty, too damaged to accommodate anything). Prior to the war, Prior to the war, Spc. Crystal Davis, 23, said two things she loved to do were "drive and dance." She lost one leg and now has a prosthetic. She calls that one her "good leg" — the other one needed a chunk cut out of it in order to save it, and gives her more trouble because it is still attached to her. Still, two weeks prior to filming, she danced — really danced, you can see the footage. You can also see her fitting her leg over the stump just before. This movie isn't for the squeamish.

Prior to the war, Cpl. Michael Jernigan, 28, had been married. But then he lost his eyes in an explosion, and he came home and his marriage fell apart under the strain. Now he wears the diamonds from his wedding band in his prosthetic eye (the left one; the right socket is empty, too damaged to accommodate anything). Prior to the war, Prior to the war, Spc. Crystal Davis, 23, said two things she loved to do were "drive and dance." She lost one leg and now has a prosthetic. She calls that one her "good leg" — the other one needed a chunk cut out of it in order to save it, and gives her more trouble because it is still attached to her. Still, two weeks prior to filming, she danced — really danced, you can see the footage. You can also see her fitting her leg over the stump just before. This movie isn't for the squeamish.

It's not for the squeamish not only because you can see stumps where legs were and empty eye sockets and faces patched up from where shrapnel blew in and lodged up, as in the case of Staff Sgt. Jay Wilkerson, 41. It's also hard to watch seeing how these terrible injuries have affected these people, like First Lt. Dawn Halfaker, 27, so tough, talking about peeing in a water bottle in convoy as part of her goal of leading the men under her command, appearing without her prosthetic arm because that's who she is, but choking up at the nagging worry about whether her kids, if she ever has them, could love her as she is. Still, Halfaker told HuffPost's Katie Halper that she'd do it all again, given the choice. Or like Cpl. Jonathan Bartlett , 22, who wrote about it on

It's not for the squeamish not only because you can see stumps where legs were and empty eye sockets and faces patched up from where shrapnel blew in and lodged up, as in the case of Staff Sgt. Jay Wilkerson, 41. It's also hard to watch seeing how these terrible injuries have affected these people, like First Lt. Dawn Halfaker, 27, so tough, talking about peeing in a water bottle in convoy as part of her goal of leading the men under her command, appearing without her prosthetic arm because that's who she is, but choking up at the nagging worry about whether her kids, if she ever has them, could love her as she is. Still, Halfaker told HuffPost's Katie Halper that she'd do it all again, given the choice. Or like Cpl. Jonathan Bartlett , 22, who wrote about it on

HuffPost last week. "I went from being G.I. Jon to being a broken mess," he writes. "Everyone has it: the image of who you are in your head. Mine shattered that day almost three years ago." Bartlett writes of "screaming in rage and frustration"; you can see some of that in his tight, defiant responses to Gandolfini's gentle questions. You can also see him hanging out at home with his mom and cat, making videos and looking forward, interspersed with shots from his convalescence, pulling himself up on a bar from a hospital bed without the help of his legs, which were both blown off. But it's guy he is now that stays with you. It's pretty awe-inspiring.

HuffPost last week. "I went from being G.I. Jon to being a broken mess," he writes. "Everyone has it: the image of who you are in your head. Mine shattered that day almost three years ago." Bartlett writes of "screaming in rage and frustration"; you can see some of that in his tight, defiant responses to Gandolfini's gentle questions. You can also see him hanging out at home with his mom and cat, making videos and looking forward, interspersed with shots from his convalescence, pulling himself up on a bar from a hospital bed without the help of his legs, which were both blown off. But it's guy he is now that stays with you. It's pretty awe-inspiring.

Gandolfini, as host and producer, keeps it out of the political, just focusing on these stories (though it's a pretty powerful anti-war statement on its own). As a host, he gentle and patient, allowing long silences to just happen, not feeling the need to jump in and fill the dead air. It's not dead  air at all, it's these soldiers grappling with what their lives have become, and how they are coping with that. The focus is on family: Cpl. Jacob Schick, 24, gets married; Sgt. Eddie Ryan, 22, is wheelchair bound and cared for by his mom, but they have a patter that speaks to what they (still) have now (Her: "Do you want to walk today?" Him: "No, I want to run." And then they laugh). Meanwhile, Cpl. Michael Jernigan, 28, just wants to hang out with his kids (and their drawing of him with one leg, and then with his "robot legs" are particularly moving). It doesn't get much more political than singing "Proud To Be An American." That they all seem to be. Harder to divine is where Gandolfini stands; he just seems to be pretty damn moved. Without the Sopranos-infused menace, he is a surprisingly gentle and comforting presence.

air at all, it's these soldiers grappling with what their lives have become, and how they are coping with that. The focus is on family: Cpl. Jacob Schick, 24, gets married; Sgt. Eddie Ryan, 22, is wheelchair bound and cared for by his mom, but they have a patter that speaks to what they (still) have now (Her: "Do you want to walk today?" Him: "No, I want to run." And then they laugh). Meanwhile, Cpl. Michael Jernigan, 28, just wants to hang out with his kids (and their drawing of him with one leg, and then with his "robot legs" are particularly moving). It doesn't get much more political than singing "Proud To Be An American." That they all seem to be. Harder to divine is where Gandolfini stands; he just seems to be pretty damn moved. Without the Sopranos-infused menace, he is a surprisingly gentle and comforting presence.

Less comforting: The images from Iraq, courtesy of embedded cameras on Humvees (like the one on Staff Sgt. Wilkerson's, which caught the explosion that injured him and killed his best friend) or, even more courteous, from insurgent released videos, like the one that captured the explosion that cut Anderson's gymnast career short (click on any of the images below to enlarge).

Things blow up in this documentary, for real. Not to get political, but they often seem to blow up on humvees — traveling vehicles, not armored, protected vehicles like MRAPs, which probably could have saved some lives. One soldier spoke of a humvee being half-blown off, taking a soldier with one half, but leaving his legs behind. Again, not for the squeamish.

20 Years Of Free Journalism

Your Support Fuels Our Mission

Your Support Fuels Our Mission

For two decades, HuffPost has been fearless, unflinching, and relentless in pursuit of the truth. Support our mission to keep us around for the next 20 — we can't do this without you.

We remain committed to providing you with the unflinching, fact-based journalism everyone deserves.

Thank you again for your support along the way. We’re truly grateful for readers like you! Your initial support helped get us here and bolstered our newsroom, which kept us strong during uncertain times. Now as we continue, we need your help more than ever. We hope you will join us once again.

We remain committed to providing you with the unflinching, fact-based journalism everyone deserves.

Thank you again for your support along the way. We’re truly grateful for readers like you! Your initial support helped get us here and bolstered our newsroom, which kept us strong during uncertain times. Now as we continue, we need your help more than ever. We hope you will join us once again.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

20 Years Of Free Journalism

For two decades, HuffPost has been fearless, unflinching, and relentless in pursuit of the truth. Support our mission to keep us around for the next 20 — we can't do this without you.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

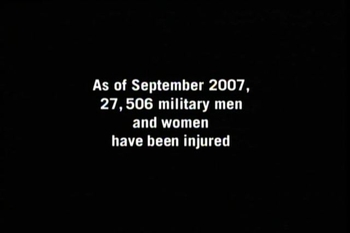

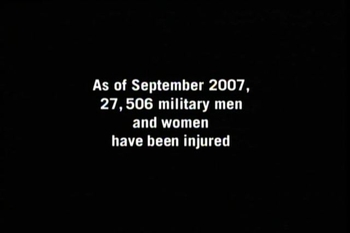

Here's why this documentary is worth writing up in such detail on a media blog: Because these aren't really the stories that are told, or the statistics that are bandied about. Most people have a general sense of where the current death toll of Americans in Iraq is these days — as of Sept. 2007 and this film's final print, 3,728; as of today, 3,771, according to the Iraq Coalition Casualty Count — but you don't hear about the 27,506 injured in the same way, nor do you see the extent of their injuries (Sgt. Anderson, for example, had 40 operations and spent 13 months at Walter Reed). According to the film, more veterans are returning as amputees since the Civil War. With the exception of Pvt. Dexter Pitts, 22, the focus is not on post-traumatic stress disorder; not sure if the 27,506 number includes that but I'm guessing not (nor is there inclusion of post-return deaths due to suicide, which is also an issue).

Jon Bartlett makes the point that these are perspectives that don't make it out all that much, either:

You don't see too many accounts of men and women in the field, or at least I have not...The news and the media don't give you truth no, they entertain and inform about things their viewers may want to know. However this documentary isn't what military men and women would talk about; the politics or the best way to shoot someone from 500 meters or how the navy is. No, we went and we all went because we had to go and then we got hurt and are now dumped back in the world.

"Dumped back in the world" — it's a reminder that "fighting them over there so that we don't have to fight them over here" has led to a different sort of fight, over here, and one that is overlooked as attention is focused, well, over there. Alive Day  Memories is a bubble-shattering film — no, things are not okay and guess what, these people are coming back broken and that needs to be acknowledged. As mentioned above, their stories stand as a pretty convincing anti-war position, but they stand just as much for the ideals that compel young men and women to sign up for the service in the first place. Whatever one thinks of the war, it's pretty clear that these ten people deserve only our love and honor and respect. Who would have thought it would be Tony Soprano who would lead that by example.

Memories is a bubble-shattering film — no, things are not okay and guess what, these people are coming back broken and that needs to be acknowledged. As mentioned above, their stories stand as a pretty convincing anti-war position, but they stand just as much for the ideals that compel young men and women to sign up for the service in the first place. Whatever one thinks of the war, it's pretty clear that these ten people deserve only our love and honor and respect. Who would have thought it would be Tony Soprano who would lead that by example.

Here are the ten soldiers profiled by Gandolfini in Alive Day Memories, beside a screengrab of Crystal Davis dancing:

Sgt. Bryan Anderson, 25

Sgt. Bryan Anderson, 25

Cpl. Jonathan Bartlett , 22

Spc. Crystal Davis, 23

First Lt. Dawn Halfaker, 27

Cpl. Michael Jernigan, 28

Staff Sgt. John Jones, 29

Pvt. Dexter Pitts, 22

Sgt. Eddie Ryan, 22

Cpl Jacob Schick, 24

Staff Sgt. Jay Wilkerson, 41