In the face of a recession that has destroyed billions in family savings and home values, Americans remain convinced that personal initiative and hard work are the key to big rewards, and they continue to repudiate the idea of government intervention to alleviate economic inequality, according to two Pew-sponsored reports.

Not only do voters continue to be convinced, by large majorities, that they, and not government or big corporations, control their own destinies in the midst of the current recession, but they do so despite more long-term evidence suggesting that there is less class mobility in the United States than in most Northern European countries, or in Canada, and that U.S. wages have not kept up with productivity gains for the past three decades.

This conviction underpins the long-standing American hostility to a full-fledged welfare state -- along the lines of many European counties -- and underpins the lack of a strong socialist tradition in the US. It also shapes the debate over policies to deal with the current recession, including the Obama administration's rejection of bank nationalization.

A survey of 2119 respondents conducted by the Democratic firm Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research and the Republican firm Public Opinion Strategies for the Pew Economic Mobility Project asked: "Currently the country is in a recession. Do you believe it is still possible for people to improve their economic standing?"

Eighty percent answered "yes," including 56 percent answering "strongly" in the affirmative. Only 16 percent said "no."

African Americans, Hispanics and persons under 40 were even more affirmative than the public as a whole, with "yes" to "no" ratios respectively 83-15, 86-11, and 85-13.

A report on the findings of the survey, produced by the two polling firms, declared: "In the midst of an historic economic crisis, Americans insist that, despite the recession, it is still possible for people to improve their economic standing, and most believe that they control their economic destiny. Americans believe ambition, hard work and education primarily drive mobility, rather than outside forces like the current state of the economy."

The continuing strength of what amounts to an American 'ethos' -- a dimension of what some scholars call 'American Exceptionalism' -- was evident in the following conclusions:

"Americans care more about opportunity than inequality and are far more concerned about the ability of lower-income Americans to move up the income ladder than about the persistence of upper-income Americans at the top. By a 71 to 21 percent margin, Americans believe it is more important to give people a fair chance to succeed than it is to reduce inequality in this country. Each demographic subgroup, including those at the lowest end of the economic spectrum, concurs with the majority on this issue."

What makes these findings particularly striking is the evidence that -- according to a second study, "Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well?," by Isabel Sawhill of the Brookings Institution and John E. Morton of the Pew Charitable Trusts -- the "American Dream" is not working as effectively as it has in the past.

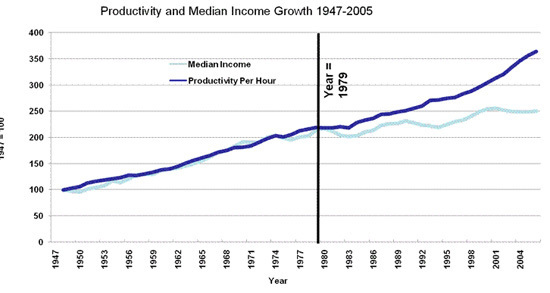

According to the Brookings/Pew report, the pay-off for hard work has been diminishing. In the three decades after WWII, workers' wages rose almost exactly in proportion to productivity gains. For the past three decades, however, wage increases have fallen significantly behind productivity gains. The following Pew chart shows this spread beginning in the late 1970s and steadily growing over time.

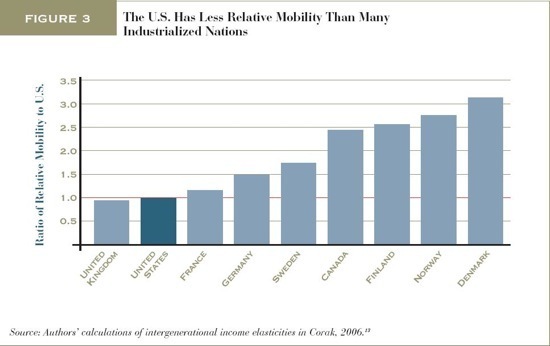

Supporters of the theory that America is an 'exceptional' nation argue that the United States is different from other countries because a) it does not grapple with a legacy of rigid social stratification, as many other countries with formerly feudal or caste systems do; and b) that Americans' strong historic opposition to 'collectivist' forms of social intervention and a relatively greater preference for 'individualism' have led to higher levels of economic mobility than are found elsewhere.

The findings of the Pew/Brookings study, however, dispute this.

What this chart shows is that there is less mobility in the U.S. than in France, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Finland, Norway and Denmark (England has lower levels of social mobility than the U.S.); that sons are more likely to earn close to what their fathers made in the United States (after adjusting for inflation) than in most of the other developed countries cited in the study.

Despite these trends, the 'individualistic' convictions of Americans remain strong, and are powerful factors in policy decisions.

President Obama, in rejecting nationalization of banks as a way to deal with collapsing financial institutions cited the alien character of such actions to this country.

Acknowledging that Sweden had successfully nationalized banks during an earlier financial crisis, Obama noted that that not only are there vastly more banks in the U.S. than in Sweden, but "we also have different traditions in this country. Obviously, Sweden has a different set of cultures in terms of how the government relates to markets and America's different. And we want to retain a strong sense of private capital fulfilling the core -- core investment needs of this country. And so, what we've tried to do is to apply some of the tough love that's going to be necessary, but do it in a way that's also recognizing we've got big private capital markets and ultimately that's going to be the key to getting credit flowing again."

* * * * *

In practice, the public may be more ambivalent about activist government, and perhaps even about bank nationalization. Rasmussen Reports conducted a survey of 1,000 adults on February 3 and 4, 2009, putting the questions of nationalization in extreme terms, "Should the Government take over our banking system and have one centralized government bank?" Not very surprisingly, some 75 percent of respondents said no, only 9 percent said yes, with the remainder either declining to answer or suggesting another alternative.

A month later, Newsweek asked 1,203 adults a parallel, but much more moderate, version of the nationalization question: "Temporary nationalization is another way for the federal government to deal with large banks in danger of failing. This is where the government takes over a failing bank, cleans its balance sheets, and then quickly sells it off. In general, which do YOU think is the better way to deal with failing banks?" Again, not very surprisingly, the response was 56 percent for "nationalization where the government takes temporary control" and 29 percent for "government financial aid without any government control of the bank."

On a broader -- and perhaps most illuminating -- scale, Newsweek asked: "In general, government grows bigger as it provides more services. If you had to choose, would you rather have a smaller government providing less services, or a bigger government providing more services?"

Republicans preferred smaller government by a 67-24 margin; Democrats were the mirror opposite, choosing bigger government by better than two to one, 65-25; independents slightly favored smaller government, 45-42.

Reflecting the nation's deep ambivalence on this issue, when all the numbers are added together, the respondents split right down the middle, 44 to 44.