This story has been edited slightly since publication for clarification.

Undeterred by their sullied reputation, big banks and credit card companies are making a major play to protect a key source of profit: credit card swipe fees.

Last year, the country's largest financial institutions -- including many banks that have received bailout funds -- raked in an estimated $48 billion from credit card swipe fees. That's an average of $400 per American household.

Every time a shopper swipes his credit card, multiple fees are triggered. The most controversial is the "interchange fee," which the merchant's bank pays to the bank that issued the credit card. Rates vary, but it averages around 2 percent of the transaction. Even as technology has reduced the costs of processing the transactions substantially, the amount of money generated by credit card swipe fees has continued to rise. Since 2001, revenue from "interchange fees" has gone up 120 percent in the United States.

Industry representatives say that the purpose of the fee is to cover the costs and risks of credit card transactions, which have increased over the years.

But critics say the system isn't fair. The banks themselves, after all, are responsible for the proliferation of credit cards. And because more people than ever are using plastic as a form of payment, merchants have been forced to raise the price of goods to compensate for the rise in associated swipe fees.

"If their risks have gone up exponentially, it's because they're issuing cards to everyone," said John Emling, senior vice president of government affairs at the Retail Industry Leaders Association. "The claim that they're somehow not responsible for the assumed risk is just a false claim."

Legislative attempts to change the system have been met by a major lobbying and advertising pushback. Spearheading that effort has been the Electronic Payments Coalition. The coalition's membership reads like a who's who of bailed-out institutions, including Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Barclay's and JP Morgan Chase.

The main battle has revolved around an obscure but aptly named piece of legislation called the Credit Card Fair Fee Act. The Senate version of the bill will empower retailers to negotiate interchange fees with banks and credit card companies, with disagreements to be settled by a three-person, independent arbitration panel. The House version is much the same, and both would require better transparency measures for all transactions between banks, credit card companies and retailers.

Retailers, led by the Merchants Payments Coalition, have run what one official described as a "mid-six-figure" advertising campaign in support of the reform measures on the radio, the Internet and in print.

They have been outspent by the EPC, which has paid $260,000 in lobbying already in 2009 and spent close to $500,000 dollars in 2008. The Coalition, which also includes MasterCard Worldwide and Visa Inc., has hired 10 former congressional staffers as lobbyists to push their legislative agenda, according to a review of public records. The EPC also has run a slew of ads in some of Washington D.C.'s most widely read websites, including Roll Call and Politico as well as on the radio. The group has been running ads on the Huffington Post as well.

One of the radio ads:

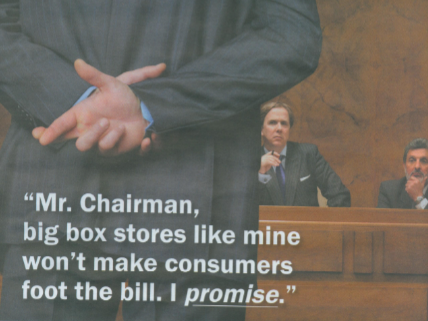

One of the print ads:

The combined effort has been to protect the status quo, with the main argument being that if the fees were changed, the merchants would merely pocket the money rather than passing the savings on to consumers.

In the context of the current economic crisis, it is an odd spectacle: The architects of the subprime mortgage crisis and the largest financial meltdown since the Great Depression -- many of whom are currently dependent on taxpayer funds -- have styled themselves as champions of consumer rights, protecting unsuspecting shoppers from predatory retailers.

"If I could sum up the debate," said Trish Wexler of the EPC, "the bottom line is that merchants don't want to pay their fair share. Instead, they want to shift that cost onto their customers."

"Merchants should pay their share," echoed the ads.

According to a statement issued by Visa, the legislation "would significantly and negatively impact consumers, especially those struggling in this time of economic uncertainty."

Not everyone is buying it.

"It is a bizarre argument because it essentially says, 'let's keep ripping folks off because if we don't someone else will,'" added Rep. Peter Welch (D-Vt.). Welch is a cosponsor of the Credit Card Interchange Fees Act of 2009, which would significantly alter the credit card swipe fee process.

As Welch sees it, the current system is unfairly tilted in favor of the bank and credit card companies. Interchange fees, he says, are unilaterally set by the credit card companies. High-end credit cards with reward programs, for instance, tend to have higher fees. Debit card and PIN transactions have lower associated rates, as do cards issued by credit unions. Under the existing system, retailers are generally unable to charge customers different rates based on the form of payment they choose. That is why retailers say they are often forced to raise the prices of all their goods in order to keep up with interchange fees.

"The person that pays cash is subsidizing the person who's getting rewards of frequent flyer miles," said Emling.

This past year, Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), attempted to attach an amendment to the Credit CARD Act of 2009 that would have prohibited credit card companies from taking action against retailers who offered reduced prices to customers paying with cash, checks or debit cards instead of credit cards. It was ultimately removed from the bill.

Since then, Durbin, Welch and other lawmakers have sought to pass the measures as stand-alone legislation. The hope is that it will be considered at some point in the year ahead. In the interim, the debate is being reframed as a matter of transparency.

It's an effort to make the issue less objectionable, but many in the banking industry maintain that new legislation is not necessary.

"The banks are fighting this tooth and nail," said Welch, "It is pretty stunning. Why would the banks be against transparency? Why? What do they fear... the fear is people might know what they are going to charge and say, you know what, I don't need this credit card."

Sam Stein contributed reporting to this article.