We have seen the "likely voter" polling problem rear its head several times in recent weeks, but few examples have been as vivid as three national surveys released in the last 24 hours.

First, Rasmussen Reports released their latest weekly automated survey of likely voters, which shows Republicans leading by a narrow 3-point margin (45% to 42%) on the question of which party's House candidate voters prefer in their own district. A few hours later, Gallup published two sets of results, each based on slightly different applications of its classic likely voter model. These showed Republicans winning the generic by huge margins of either 13 points (53% to 40%) or 18 points (56% to 38%), depending on the assumptions they made about the level of turnout. Meanwhile, a new survey out this morning from ABC News and The Washington Post put the Republican margin on the generic House ballot question at 6 points (49% to 43%).

Needless to say, those numbers can't all be right. The enormous variation has left a lot of reporters and readers emailing to ask, just how do pollsters identify a likely voter? More important, does anyone know what the heck a likely voter is anymore?

That question is arguably the most important polling story of the year. The answer is not obvious, but the basic issue is simple. There were roughly 213 million eligible adults in 2008, but only about 68% of those adults told the U.S. Census that they were registered to vote and only 62% turned out to vote (up from 60% in 2004). More important, turnout is typically much lower in midterm elections. The turnout among eligible adults was 40% in both 2006 and 2002.

So conceptually, this is a simple problem: It doesn't make sense to interview a sample that represents all registered voters, when somewhere between a third and half of those who say they are registered voters will not vote.

The hard part is figuring out who the true "likely voters" really are. Part of the problem, of course, is that some of those who will actually vote don't know yet that they will (and vice versa). To paraphrase my friend, political scientist Joel Bloom, the 2010 electorate is "a population that technically does not yet exist." It is, rather "in the process of becoming one."

But why not just ask people whether they plan to vote? You can, and pollsters do, but the challenge is that survey respondents often exaggerate their true intentions, even on the eve of an election. Consider the following questions asked by the Pew Research Center less than a week before the midterm elections of 2006 (I've recalculated their results out of a base of all adults):

- 68% said they were registered and planned to vote in the upcoming election

- 54% said they were registered and rated their likelihood to vote as a 10 on a scale of 1 to 10

The obvious problem there is that just a few days later, only 40% of eligible adults actually voted. Obviously, many voters will say the they plan to vote when the don't.

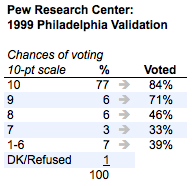

Despite these problems, "do you plan to vote" questions do have some predictive value, as shown by an experimental survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 1999. The Pew pollsters did a pre-election survey on the Philadelphia mayor's race, then after the election, used public records to identify which of their respondents actually voted. Their vote "validation" data shows that the 10-point likelihood question was modestly predictive of voting, even if many of the "very likely" respondents did not vote. As the following table shows, those who rated their likelihood of voting as a 10 on a 10-point scale were more likely to have actually voted (84%) than those who rated their likelihood as a 9 (71%), an 8 (46%), or 7 or lower (roughly 37%).

A separate calculation showed that if they had simply classified as "likely voters" those who rated their likelihood of voting as 7 or higher, they would have correctly classified 77% of the registered voters they interviewed. So this sort of measure provides a crude if imperfect way of at least getting closer to the likely electorate.

There are other questions that are crudely predictive of actual voting. Drawing again from that final week 2006 Pew Research poll, some examples include voters who report:

- Having previously cast a vote in their precinct (65% of adults)

- Always or nearly always voting (63%)

- Knowing where people in their neighborhood vote (63%)

- Following "what's going on in government and public affairs" most or some of the time (63%)

- Giving some or a lot of thought to the upcoming election (50%)

Again, none of these are perfect predictors of turnout, and the percentage answering in the affirmative in each case still far exceeds the actual turnout of eligible adults in 2006. However, the 1999 Pew study confirmed that those who report greater intent to vote, a history of past voting, knowledge of voting procedures or high interest in or knowledge about politics a week or so before an election are more likely to vote than those who do not.

In the 1950s, Paul Perry, the legendary president of the Gallup Organization, combined seven questions much like these into an index. The greater respondents score on the index, the greater the the probability that they would vote He then made an educated guess about the likely level of voter turnout -- say 40% of adults -- and used the index to select the 40% of the sample that scored highest on the index. That procedure proved to produce more accurate election forecasts than alternatives they tested, and remains the basic concept still used in the Gallup likely voter model to this day.

Over the years, other media pollsters adopted similar approaches. Gallup still uses it, of course, and pollsters like the Pew Research Center and the ABC/Washington Post poll and others continue to apply close variants.

While the Gallup-style model has its critics, let's set those issues aside for a moment and focus on this point: The classic, seven-question, Gallup-style index-and-cutoff model represents a minority of the "likely voter" polls we are now seeing at the statewide level. Moreover, the approaches that pollsters use vary widely, and resist easy categorization. The simplest way to describe what they do is to say there are a variety of different techniques that various pollsters mix and match. Aside from the classic Gallup model, these include:

- The CBS/New York Times variant, which is similar to the Gallup approach except that rather than select specific respondents as likely voters, it weights all registered voters up or down based on their probability of voting.

- The use of two or three questions to simply screen out voters at the beginning of the interview that say they are not registered and not likely vote.

- The application of quotas or weights to adjust the completed interviews to match the pollster's expectations of the demographics or regional distribution of likely voters.

- The application of quotas or weights to match the pollster's expectations of the party affiliation of likely voters. I break this one out separately because it remains among the most controversial likely voter "modeling" tools.

- Sampling respondents from lists that draw on official records of the actual vote history of individual voters, so that when the pollster calls John Doe, they already know whether Doe has voted in past elections.

- Finally, many believe that the use of an automated, recorded-voice methodology rather than a live interviewer is itself a useful tool in obtaining a more accurate measurement of the intent to vote.

Some pollsters use a few of these methods, some use nearly all, so there are probably as many likely voter "models" out there as there are pollsters.

The tools that pollsters apply also reflects a philosophical difference I have written about before: Most national media pollsters, especially those that apply the classic Gallup index-and-cutoff model, are wary of making a priori judgments about the demographics or attitudes of the likely electorate. They prefer to set up a theoretically-objective mechanism to determine what a likely voter is and trust it to determine the demographics and partisan balance of their sample.

On the other hand, most (but not all) campaign pollsters -- those who (like me in a former life) conduct surveys on behalf of political campaigns -- have grown comfortable about drawing on data from other sources and applying their own judgment about the demographics and even the party identification of the likely electorate.

All of these factors help explain why different polls that all theoretically measure the same "likely" electorate can produce very different results.

Of course, the biggest question of all is whether these tools are working as well in this tumultuous election year as they have in the past. That's the question that I'll take up in the second part of this series.