The Federal Reserve said growth will lag this year as the central bank finally acknowledged Wednesday what most Americans have long since realized: “Inflation has picked up.”

The Fed’s statement, a customary event at the conclusion of every policy meeting, is the status update traders, bankers, businessmen and policy makers use to gauge the health of the U.S. economy.

The Fed's recognition of rising inflation did not affect its easy-money policy, though. The main interest rate will remain anchored near zero percent. Its asset-purchase program will also continue and run through its scheduled completion in June.

It will be another "couple of meetings before action," Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said during a news conference. There are five more meetings scheduled this year.

The Fed's preferred measure of inflation guides its policy decisions. That index, which is about a full percentage point lower than what consumers experience at the pump or when buying food at the register, strips out volatile prices that are not always representative of the broader price of goods. By the Fed's measure, inflation is not yet a worry.

The recovery is “proceeding at a moderate pace,” the Federal Open Market Committee, the Fed’s main policy making body, said in its statement. Last month, the recovery was simply “on a firmer footing.”

The Fed lowered its estimates for growth by about half a percentage point. In January, the central bank forecast U.S. gross domestic product to rise about 3.4 to 3.9 percent in 2011 during the final three months of the year. It now forecasts GDP to increase by about 3.1 to 3.3 percent.

Even though growth is expected to be lower, the Fed predicted reduced unemployment compared to its earlier estimate as well -- even though the measures typically move in opposite directions. Policy makers are more confident in the strength of the labor market, which they said is finally improving, albeit “gradually.” Last month, the Fed would only say that it appeared to be getting better.

The unemployment rate stood at 8.8 percent at the end of March, according to the Labor Department. The central bank forecasts unemployment to average 8.4 to 8.7 percent during the last three months of the year, a slight improvement from January's forecast of 8.8 to 9.0 percent.

But the part of the Fed’s statement that will likely be parsed by traders on Wall Street is the realization that “inflation has picked up in recent months,” which the Fed attributes to rising energy and commodity prices.

Most Americans began recognizing this a few months ago.

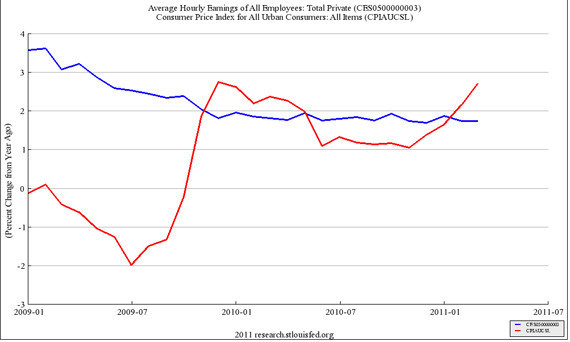

Last month, prices including food and energy rose 2.7 percent on an annual basis, Labor Department data show. Bernanke said the rate is "noticeably higher" than normal.

The price of food eaten at home has risen 3.6 percent. Meats, poultry, fish and egg prices are up 7.9 percent.

The average price for unleaded gasoline stands at $3.88 per gallon, according to the American Automobile Association. A year ago today, fuel cost $2.86 per gallon. It’s risen 36 percent, a development Bernanke acknowledged is causing pain for working families.

Prices have increased so much so fast that it’s eating into incomes and purchasing power.

Hourly earnings are up only 1.7 percent over the past year, according to the Labor Department. But, when factoring inflation, wages are down 1 percent.

That statistic is part of the reason why the Fed has been so aggressive in keeping interest rates as low as possible, a policy it reaffirmed Wednesday. Low interest rates spur borrowing, which should lead to spending, investing and, theoretically, hiring and higher wages.

The Fed will keep the main interest rate anchored at 0 percent and will continue its asset-purchase program through completion in June, it said. The central bank has about $2.7 trillion in Treasuries and mortgage-linked securities.

Another reason behind the Fed’s continued aggressiveness in the face of rising consumer prices -- firms like Nike and Wal-Mart say they’re passing on commodity price increases to customers -- is the central bank’s preference for an alternative measure of inflation.

The Fed looks at so-called core inflation, a measure that strips out food and energy prices, when gauging the inflation rate that will guide its policy decisions.

By that measure, prices are up only 0.9 percent in the year ending in February, according to the Commerce Department. The Fed aims to maintain the rate at about 2 percent.

“Measures of underlying inflation are still subdued,” the Fed said Wednesday. The inflationary effect of higher commodity prices will be "transitory."

But the central bank's inflation forecasts surged.

In January, the Fed estimated that prices will rise at an annual rate of 1.3 to 1.7 percent during the final three months of the year. It now projects prices to rise 2.1 to 2.8 percent, about a full percentage point higher.

Bernanke faces a dilemma, reckoned Bernard Baumohl, chief economist of the Economic Outlook Group.

"There is no greater curse on Fed policymakers than the combination of a slowing economy and accelerating inflation, especially when both are largely the result of events taking place outside the U.S.," Baumohl wrote in a note to clients. "In this instance, it is the robust demand for food and fuel coming form fast-growing emerging countries and the geopolitical turmoil that has spread across the oil-rich regions of North Africa and the Middle East. And neither of these foreign dynamics show signs of de-escalating."