This is an adaptation from "Reckless Endangerment", an exploration of the origins of the recent financial crisis, by Gretchen Morgenson and Joshua Rosner. The book will be published Tuesday by Times Books. This excerpt examines Wall Street's role in the crisis and the relationship between Goldman Sachs, a leading investment bank, and Fremont, a freewheeling mortgage lender. Goldman declined to respond to detailed interview requests for this book.

Of all the partners in the homeownership push, no industry contributed more to the corruption of the lending process than Wall Street. If mortgage originators like NovaStar or Countrywide Financial were the equivalent of drug pushers hanging around a schoolyard and the ratings agencies were the narcotics cops looking the other way, brokerage firms providing capital to the anything-goes lenders were the overseers of the cartel.

Just as drug lords know that their products pose hazards to their customers, the Wall Street firms packaging and selling mortgage pools to investors knew well before their customers did that the loans inside the securities had begun to go bad.

It was a colossal breakdown in the duty Wall Street owed to its investing customers.

Years after the meltdown, investors began to understand how badly they'd been burned by Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Lehman Brothers, Deutsche Bank, Greenwich Capital, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and other smaller firms. Lawsuits against these firms alleging a dereliction of duty started cropping up in 2010 as investors began to realize that Wall Street's secret loan assessments had identified severe problems in mortgages well before they stopped selling them.

Unlike many other firms, Goldman Sachs went negative on the mortgage market in the fall of 2006, well before others in its industry. Using its own money, the firm began amassing major bets against the same dubious loans it was peddling to investors at that time. Goldman, therefore, profited immensely from the losses its clients absorbed, losses its own practices helped to create.

It is unclear whether Goldman put on its hugely profitable and negative mortgage trades because of proprietary information turned up in its due-diligence reports. If that was indeed what happened, its failure to tell clients of the problems in the loans it was selling is even more disturbing.

Wall Street had financed questionable mortgages before, of course. But it was during the mania's climactic period of 2005 and 2006 that these firms' activities as the primary enablers to freewheeling lenders really went viral. No longer were the firms simply supplying capital to lenders trying to meet housing demand across America. Now Wall Street was supplying money to companies making increasingly poisonous loans to people with no ability to repay them. And the firms knew precisely what they were doing.

The relationship forged by Wall Street's most prestigious firm, Goldman Sachs, with one of the nation's most wanton mortgage originators -- Fremont Investment & Loan -- is a case in point. Fremont, a company with a regulatory rap sheet and a history of aggressive lending, received $1 billion in financing from Goldman in 2005, fully one-third of the total it received from all of its Wall Street enablers.

Goldman had begun financing Fremont's workers' compensation insurance unit in 2003 with a credit line of $500 million, but as the mortgage spree ramped up, it doubled that commitment. Goldman did so in spite of a serious run-in Fremont's insurance unit had had with regulators just five years earlier.

With one of its units in operation since 1937, Fremont was no upstart lender like New Century or many of the other mortgage companies cropping up all over Southern California. Based in Santa Monica, Fremont boasted $8 billion in assets and declared its 100th consecutive quarterly cash dividend in November 2001.

The company was something of a family business, overseen by founder and patriarch Lee McIntyre, who had launched the company in 1963 with $800,000 in capital. Lee brought his two sons, David and James, into the business in the 1960s. David ran Fremont's insurance operations while James ran the banking unit.

In 1969, James took up the task of decorating the company's headquarters. He commissioned the world- renowned photographer/naturalist Ansel Adams to print 121 of his silver gelatin photographs of American parks and monuments to hang on Fremont's walls. Some were massive, the size of murals, and Adams worked closely with McIntyre on the installation over five years. It was the largest private collection -- much bigger than that of any museum -- of Adams photographs.

The photographs sent a message to Fremont's visitors that this was not just any financial concern -- this was a classy enterprise that paid close attention to detail. When Fremont failed almost 40 years later, the artwork would become enmeshed in a fierce battle over the company's assets.

Wall Street firms helped Fremont sell its loans and they were happy to further the company's efforts to become one of the heavyweights of the subprime world. By 2000, Fremont was a giant in that world, originating $2.2 billion in mortgages. But this was only the beginning; in 2006, when the home-loan frenzy was peaking, Fremont would originate $28 billion in mortgages.

Although California insurance regulators accused Fremont executives of a scheme that boosted their pay but contributed directly to the collapse of its workers' comp insurance unit's collapse, few on Wall Street appeared to care about such problems.

* * * * *

Even as Fremont's executives were sparring with the California insurance regulator, the company was rushing to get in front of the highly lucrative parade involving subprime mortgage securitization.

In 2001, mortgage lenders like Fremont understood that the low-interest-rate environment was driving investors to securities that yielded more than Treasury bonds and other relatively conservative fixed-income instruments. The Federal Reserve Board's decision to slash interest rates to propel the economy was hurting investors who lived on the income generated by their holdings. Mortgages, with their relatively higher yields, provided a handy answer to this problem. Many investors still believed that home loans were relatively conservative instruments. Ratings agencies, blessing the majority of these securities with triple-A ratings, only confirmed this rosy view.

Teaming up with lenders, major brokerage firms like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs pressed them for loans to feed the mortgage securities machine. It didn't hurt that the fees generated by these securities made up for stagnant businesses -- such as investment banking and stock trading -- that were generating only paltry revenues on Wall Street.

With yield-hungry investors on the prowl for profits, and Wall Street eager to please, the subprime mortgage market started to rouse. The billions of dollars being dangled before cash-strapped lenders were mighty alluring; they knew that tapping those funds could juice their volumes and their profits.

In a world of tough sells, this wasn't one. The race to the bottom had begun.

With the Fed on a rate-cutting rampage, demand for adjustable-rate mortgages with relatively low initial interest costs had become incendiary. One of a raft of "affordability" products that Countrywide and other lenders were peddling to counter the effects of the housing bubble, adjustable-rate mortgages with their low rates allowed borrowers who'd previously been shut out of homeownership to join the party.

It is not surprising then that 2003 was the year to remember in mortgage originations. A record 13.6 million mortgages worth $3.7 trillion were written that year; Wall Street's issuance of mortgage-backed securities also peaked, reaching $463 billion in 2003. The top 25 lenders underwrote most of these loans. While these companies had accounted for only 28 percent of new mortgages written in 1990, by 2003, the top 25 were responsible for generating 77 percent of the $3.7 trillion in loans.

The bad news -- for Wall Street, anyway -- was that the blistering pace simply could not continue. Mortgage originations had been propelled by the Fed's rate cuts, but with prevailing rates at 1 percent, there was little room for further declines. This was meaningful because borrowers who had reached for more home than they could afford would no longer be able to lower their costs by refinancing when rates fell again.

As 2004 dawned, therefore, it had become more and more evident that the mortgage lending machine was sputtering. By midyear, Citigroup, Bear Stearns, and Morgan Stanley had all reported serious declines in their mortgage-backed securities deals. Lehman's volumes had fallen 35 percent from the previous year while Goldman Sachs's had plummeted by more than 70 percent. But instead of serving as a warning to the banks, this hiccup in loan origination only made them redouble their efforts in the subprime arena.

It was a moment of truth for Wall Street, an industry not known for veracity. The firms that had made so much money on the American dream of homeownership were faced with a decision. Recognizing that the easy money days were over, the firms knew that continuing down the path of big mortgage profits was going to require a more concerted effort, greater creativity. Wall Street, always at the ready for such duty, concocted new types of loans to be offered to borrowers as well as new entities that would buy them.

But keeping the mortgage machine humming would also require that investment banks ignore numerous signs of wrongdoing along the way. This meant putting their own interests ahead of their clients' at every turn.

While nobody mistook Wall Street banks for charity organizations, the degree to which these firms embraced and facilitated corrupt mortgage lending was stunning. Their greed and self-interest took the mortgage mania to heights (or depths, depending on your view) it could not possibly have reached without Wall Street's involvement. And in so doing, Wall Street helped propel world financial markets to the brink of collapse.

The voraciousness of these firms would also push the nation's economy into its most serious recession in more than 75 years. Their avarice would finally, and forcefully, demonstrate how a noble idea like homeownership could be corrupted into something that so poisoned the global economy it was left in a semi-vegetative state.

Recognizing how risky these loans were, Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, Goldman, and the rest were careful to bundle them with more traditional mortgages in the securities they were selling to investors. Prior to investing in the pools, prospective buyers were given only broad and generalized information about the loans inside them -- details like average borrower credit scores and average loan-to-value ratios. That meant they rarely knew how many tricky loans they wound up owning. Until they started going bad, of course.

As usual, the ratings agencies were chronically behind on developments in the financial markets and they could barely keep up with the new instruments springing from the brains of Wall Street's rocket scientists. Fitch, Moody's, and S&P paid their analysts far less than the big brokerage firms did and, not surprisingly, wound up employing people who were often looking to befriend, accommodate, and impress the Wall Street clients in hopes of getting hired by them for a multiple increase in pay.

There were other impediments to good ratings at the agencies. They had a limited history with the newfangled mortgages that were filling these instruments. Their failure to recognize that mortgage underwriting standards had decayed or to account for the possibility that real estate prices could decline completely undermined the ratings agencies' models and undercut their ability to estimate losses that these securities might generate.

The creation of collateralized debt obligations as a sort of secret refuse heap for toxic mortgages created even more demand for bad loans from wanton lenders. CDOs, which were essentially big bundles of pooled mortgages, prolonged the mania -- vastly amplifying the losses that investors would suffer and ballooning the amounts of taxpayer money that would be required to rescue companies like Citigroup and the American International Group.

While the ratings agencies were snoozing, the CDO issuers were working overtime. In 2004, CDO issuance totaled $157.4 billion; by 2005, the figure had risen to a quarter trillion. Issuance peaked in 2006 when investors bought a staggering $521 billion of this dressed-up dross.

To Wall Streeters, CDOs had several amazing attributes. First, they were often compiled and overseen by veterans of Wall Street and these CDO managers worked hand in glove with the big firms who peddled them to customers. This meant the CDO managers were often in on the con, so instead of scrutinizing closely the loans that Wall Street and their friendly originators delivered, the managers waved dubious loans in by the billions.

But CDOs had another, major allure for the Wall Street firms that peddled them. Because of the way some were structured, they allowed the firms who were selling them to bet against the clients buying them. Among the first to embrace this concept was Goldman Sachs, the most esteemed of the nation's investment banks and often the first mover in any profitable trade.

Goldman was founded in 1869 by Marcus Goldman, a German immigrant. In 1882, his son-in-law, Samuel Sachs, joined the small firm. In the early 20th century, Goldman specialized in initial public offerings, raising money for companies from public investors.

Over the years, Goldman grew into the preeminent investment bank. For decades it was run with one goal in mind -- to do best by its customers. Goldman executives were known as Wall Street's best and brightest and after serving out their time at the company often went into public service. Henry M. Paulson, the Treasury secretary during the early years of the mortgage meltdown, was the last in a long line of federal officials who came to Washington by way of Goldman.

But after Goldman gave up its private partnership structure, raising money from the public in 1999, the tone at the company changed. Profits took priority over customer care and trading desks soon dominated the firm's previous power center -- the investment banking arm. Lloyd Blankfein, a commodities trader who joined the firm when it bought J. Aron and Company, a trading house, was a driver of this shift at Goldman. He became its chief executive when Paulson left for Treasury.

Given that traders were in control at Goldman, it is not surprising that the firm's mortgage desk convinced top company officials to make a major bet against the home-loan market. Recognizing that the market was overheated and starting to cool, Goldman quietly began wagering against the very securities it was selling to its clients. This dubious practice took hold at Goldman in the third quarter of 2006. Later, other CDO managers did the same thing, betting against the instruments they were charged with overseeing for the benefit of their clients.

Investors who relied on the ratings agencies to vet the CDOs never had a chance. The agencies did not see how toxic the loans in them were; in fact the largest ratings firms didn't do loan-level analysis. Moreover, the instruments were far too complex to be analyzed by outsiders -- some contained dozens of pieces of other loan pools referencing thousands of mortgages.

As CDO issuance soared, investment banks increased their cash commitments to small lenders, securing critical loan production. They also bought their own mortgage companies so they could be sure the supply of loans met the demand fueled by CDOs. With CDO managers lapping up all manner of mortgages, lenders soon found that their production targets were harder and harder to achieve. Countrywide, NovaStar, Fremont, and the rest responded by ramping up the profits generated in each loan. This meant steering borrowers who would otherwise qualify for lower cost mortgages into highly profitable but much more toxic loans.

Borrowers who could prove that their incomes and assets were ample were pushed into more expensive loans that required no documentation. Mortgage brokers peddled them as easy and hassle-free. These and other tricks hurt borrowers. But they increased the industry's and investment banks' profits. At the same time, lenders redoubled their efforts to refinance existing borrowers into more exotic mortgage products. The push for production fueled by Wall Street's CDO factories fostered the massive growth in "liar loans," for which borrowers did not have to produce any proof of income or assets.

Behind these creative bankers stood an increasingly powerful participant in the game: mortgage-backed securities traders employed by major investment banks. Generating immense profits to their firms, these traders gained more importance every day. They became drivers of the mortgage securitization process, making decisions that regularly overrode credit risk officers whose job was to prevent the disasters that resulted from trader excess.

* * * * *

In July 2005 the executives at Fremont Investment and Loan got some very good news. Fitch Ratings had announced it was upgrading Fremont's subprime servicer rating on the strength of "notable improvements" in the company's operations.

Like many mortgage originators, Fremont did not just write mortgages, it also serviced them, performing administrative tasks such as taking in borrowers' monthly payments and tracking their escrow accounts and insurance obligations. Servicers also performed these duties for other lenders, for a fee, of course.

In order to attract business, servicers needed to garner high ratings from Fitch, Moody's, and Standard & Poor's. For Fremont, the Fitch upgrade was a shot in the arm.

In its report, Fitch noted a variety of improvements Fremont had made to its servicing unit, including "the refinement of an online central repository for policies and procedures, as well as the addition of a dedicated group of former FDIC auditors to perform ongoing regulatory assessments and reviews."

While these changes hardly seemed worthy of an upgrade, the volume of loans that Fremont churned out meant big fees for ratings agencies. Perhaps Fitch's upgrade had more to do with the future business Fremont might throw its way; after all, Fremont was servicing more than 100,000 loans totaling $19.1 billion in principal balance at the time and was projecting a servicing portfolio of $24 billion by the end of 2005. That kind of growth in a weakening environment would have made Fremont's servicing business an important relationship for any of the big three ratings firms.

The reed upon which Fitch hung its upgrade of Fremont could not have been thinner -- the creation of a central database for the company's procedures and a handful of new auditors was nobody's idea of groundbreaking. Moreover, even as Fitch was rhapsodizing about Fremont's mortgage servicing practices, some sophisticated investors were growing leery of the entire market for home loans.

In May 2005, reports surfaced that the world's largest fixed income investor, Pimco, which ran the biggest mutual fund, had retreated from the CDO market because of concerns about these instruments' deteriorating credit quality. Only a few months before, Scott Simon, head of Pimco's mortgage-backed securities unit, had warned that his team was reducing exposure to longer-maturity mortgages and were concentrating their investments in higher-grade pieces of the pools.

Unease about the effects that rising interest rates would have on the market gave investors another reason for caution in mid-2005. In August, the Federal Reserve Board increased its discount rate to 4.5 percent, up from 2 percent the summer before. The Fed was finally trying to tap on the brakes of a runaway real estate market.

Nevertheless, on Sept. 19, 2005, the day before the Fed increased rates by another quarter of a percentage point, Fitch published a new and glowing report on Fremont. This time, the ratings agency was upgrading the lender's corporate debt because of its improved financial condition. Citing "substantial recent increases in regulatory capital levels and ratios and in liquidity," Fitch said Fremont had shielded itself from potential regulatory pressure to bolster its financial footing.

The analysts at Fitch did note two risks to Fremont's business: It was concentrated in commercial real estate lending and subprime mortgage originations, operations that would both be subject to "adverse economic trends over the course of the business cycle." But Fitch said it was satisfied, and recommended that investors should be too, by the current strength in both of Fremont's markets and its current levels of capital and reserves. Both would be there to help the company through "less favorable environments."

What the analysts at Fitch had failed to recognize was the amount of capital that would be required if Fremont's loans were so toxic that they could not be sold to investors. Another possibility that Fitch overlooked: What if the investors who had already purchased Fremont loans or the Wall Street firms that were acting as middlemen began to notice how defective the loans were and forced Fremont to buy them back? Both scenarios would require immense amounts of capital from Fremont, money it simply did not have.

In early 2006, Fremont reported earnings for the previous year's fourth quarter. Profits were down 40 percent from the prior year. Although originations had risen 37 percent, Fremont's profitability on sales and securitizations had collapsed by more than half. It was clear that the train was veering off the track.

There was one peculiar bright spot in Fremont's report that should have served as a red flag to regulators and investors. Amid the bad news, Fremont announced that it had more than tripled its mortgage securitization volume, quarter over quarter and year over year.

The big increase in securitizations suggested that Fremont's lenders were pressuring it to get more mortgages out the door to investors so the financiers could get their money back before the roof caved in.

The big banks certainly had the information necessary to determine if loans made by Fremont and other lenders were more likely to default faster than normal. That's because investment banks like Goldman employed independent due-diligence firms to sample the loans they were buying or warehousing from mortgage originators.

Investors who were kicking the tires on a mortgage security would have loved to learn what these due-diligence firms were finding as lax lending took over. But they never saw the reports. They weren't allowed to; investment bankers kept them under lock and key.

Former employees at due-diligence firms say that among the banks that used them, almost half of all loans from 2006 on had material defects, with no offsetting factors. And yet these loans were pooled, packaged, and sold to investors. True, there were small warnings buried deep inside these pools' prospectuses; they consisted of the classic lawyerly hedge clause, stating that "the pool may contain underwriting exceptions and these exceptions, at times, may be material."

An investor could easily overlook 14 little words buried in a several-hundred-page prospectus.

* * * * *

In June 2006, Morgan Stanley announced it had hired two senior executives from Fremont to develop and build a "world-class" wholesale lending platform at the firm. To some it seemed unlikely that Morgan Stanley's move was about building a lending platform; a more credible explanation was that the firm needed to find ways to minimize losses on loans it had bought from Fremont that the lender could not afford to buy back. Who better to set up such operations than recent escapees from Fremont?

By August, investment banks were growing more frantic, pushing their lender partners to slash their originations of risky mortgages. The number of borrowers who were defaulting on loans within months of receiving them was rocketing; this posed severe consequences to both lenders and their enablers. "Early payment defaults," as they were known, allowed investors in the mortgage securities to return the loans to the lender and, in exchange, get their money back. If the lender didn't have enough money to repurchase the defective loans, the investment bank that provided the lines of credit to the lender could be forced to pay.

As early as spring 2006, Fremont's borrowers were reneging on their mortgage obligations in distressing numbers. Investors who had purchased some of the mortgage securities packaged by Goldman Sachs in 2006 learned this the hard way.

One of the worst concoctions ever designed and sold to investors was the GSAMP Trust 2006-s3 (the acronym stood for Goldman Sachs Alternative Mortgage Product). Issued by the firm in April 2006, the pool was swollen with Fremont loans -- 54 percent of the contents.

Within three months of the trust's issuance, more than 5 percent of the loans in the pool had become severely delinquent. Because borrowers had to have missed three consecutive payments before they were considered "severely delinquent," this meant that 5 percent of this pool's borrowers never made one payment. By August 2007, 16 months after it was issued, the pool had a 40 percent loss to liquidations.

Executives inside Goldman also began hearing horror stories about Fremont loans from clients to whom they had tried to sell Fremont-laced securities. A Nov. 16, 2006, email to her superiors from Melanie Herald- Granoff, a Goldman salesperson, described the pushback she received from a customer she had approached to buy into a Fremont securitization.

"Yesterday when I spoke with Luke and he said they were dropping from the freemont (sic) deal he said he had set up a call with them," Herald-Granoff wrote. "They are concerned about all the fremont exposure they already have, are going to put Fremont ‘in the box' for the time being."

Discussions like these as well as the information Goldman was getting from the due-diligence reports it had commissioned were making the firm's executives nervous. Obviously, the subprime bonanza was peaking or had already.

So in the third quarter of 2006, Goldman decided to make a concerted effort not only to rid itself of any mortgage assets it had on its books, it also decided to make a very big wager against the subprime sector as a whole.

Goldman didn't stop selling mortgage securities stuffed with sketchy subprime loans to its clients, mind you. Indeed, in the first three quarters of 2006, Goldman sold $17.8 billion of its own mortgage- backed securities; it also sold $16 billion in CDOs, up from $8 billion in 2005.

The firm seemed to view its customers not so much as people to watch out for, but as trading partners it could take advantage of if they were foolish enough to allow it. Savvy investors knew enough to approach warily any securities Goldman was peddling. As ever, the ratings agencies did their part to help Goldman sell the Fremont trash it had financed. In January 2007, S&P was rating a mortgage- backed security put together by Goldman Sachs filled with Fremont subprime loans.

An e-mail turned over to Congress shows an S&P analyst asking for help on the deal from two senior colleagues.

"I have a Goldman deal with subprime Fremont collateral," the junior analyst wrote. "Since Fremont collateral has been performing not so good, is there anything special I should be aware of?"

One respondent replied, "No, we don't treat their collateral any differently." The other piped up, "Are the FICO scores current?"

"Yup," was the reply. Then, "You are good to go."

In other words, the S&P analyst relied upon one element -- borrower credit scores -- in assessing whether greater credit risk should be assigned to loans made by an issuer well-known for its questionable loans. In fact, just three weeks earlier, S&P analysts had circulated an article about how Fremont had stopped doing business with 8,000 brokers because their loans had some of the highest delinquency rates in the industry.

Even so, S&P's and Moody's financial engineering justified triple-A ratings on five slices of securities backed by Fremont mortgages in the deal.

* * * * *

While Goldman's salespeople were busy bundling and selling as many Fremont loans as they could, executives inside the firm were scurrying to offload mortgages that were still on their books. It was a race against time inside Goldman in early 2007, as internal emails produced to Congress show. The paramount goal was to get rid of toxic mortgages.

In early February, Josh Rosner and Joseph Mason presented a lengthy paper at The Hudson Institute, a Washington think tank, warning of coming losses to holders of mortgage securities, and as a result, the end of credit availability to the housing market. The banks rejected the analysis even as they were quietly jettisoning those very securities from their own books.

A Feb. 2 email written by Dan Sparks, head of Goldman's mortgage department, warned superiors of looming losses on loans the firm had not yet been able to jettison. "We will take a write-down to some retained positions next week as the loan performance data from a few second lien sub-prime deals just came in (comes in monthly) and it is horrible," Sparks wrote. "The team is working on putting loans in the deals back to the originators (New Century, WAMU, and Fremont -- all real counterparties) as there seem to be issues potentially including some fraud at origination, but resolution will take months and be contentious."

Less than a week later, another Goldman employee summarized the state of the market for subprime loans in general and Fremont's in particular. An email marked "Internal Only" three times, said: "Collateral from all Subprime originators, large and small, has exhibited a notable increase in delinquencies and defaults, however, deals backed by Fremont and Long Beach collateral have generally underperformed the most."

And the minutes of a March 7, 2007, meeting of the Firmwide Risk Committee at Goldman has Sparks declaring "game over" in mortgages. His talking points also noted an "accelerating meltdown for subprime lenders such as Fremont and New Century." Nevertheless, by the end of that month, Goldman had packaged and sold to investors more than $1 billion in mortgage securities backed by Fremont loans. It had also placed internal bets against the same Fremont loans it was selling to its customers.

* * * * *

Sparks was certainly right about the game being over in March 2007. Investment banks were furiously pulling in ware house lines, cutting off oxygen to the lenders once lauded as the driving force behind Wall Street's earnings. Borrowers who had been given risky loans and who had grown accustomed to refinancing their mortgages to take cash out of their homes suddenly found no replacement loans available to them, even at higher initial interest rates. Early payment defaults roared higher.

The machine that Wall Street had built was faltering. Lenders that still had cash were receiving calls for it from investors.

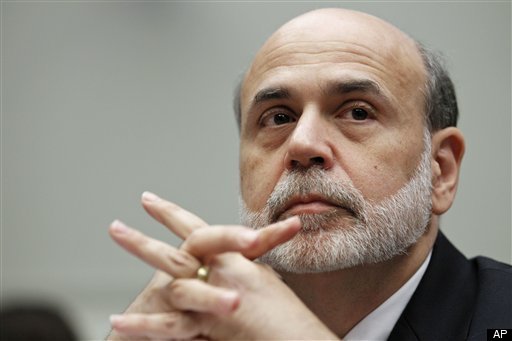

The problems were becoming clear enough, but few regulators seemed to notice the calamity in the making. Capitol Hill, for its part, was asleep. As the housing market rotted from the core, Ben Bernanke expressed his concern about inflationary pressures and Tim Geithner, president of the powerful New York Fed, sounded warnings on unregulated hedge funds.

Testifying before the Congressional Joint Economic Committee in March 2007, Bernanke, considered a scholar on central banking, said, "The impact on the broader economy and financial markets of the problems in the subprime market seems likely to be contained." And later that month, Paulson, the secretary of the Treasury who had recently run Goldman Sachs, echoed Bernanke's view that the mortgage crisis would not infect the overall economy or world financial markets.

"It looks to me like this housing issue is going to be contained," Paulson told members of Congress on March 28. Never mind that many of the most disastrous securities had been created by Goldman during the Paulson years.

Things were decidedly not contained at Fremont, however. That month, the company noted in a regulatory filing that the California Court of Appeals had ruled against it in a lawsuit that had been brought by the California insurance commissioner. The commissioner had found that Fremont was selling adjustable-rate mortgages to subprime borrowers "in an unsafe and unsound manner that greatly increases the risk that borrowers will default on the loans or otherwise cause losses."

At the same time, Fremont was visited with a cease and desist order from the FDIC, a regulatory action that was the kiss of death for a financial institution. The FDIC enumerated 14 problematic practices at Fremont, including operating without effective risk- management policies and with a large volume of poor- quality loans, and conducting business without sufficient capital or liquidity.

In April 2008, Fremont announced that it received default notices on over $3 billion of subprime mortgages it had originated in March 2007 and that it did not have the cash to buy back the loans as promised. In fact, Fremont Investment and Loan did not even have the minimum of $250 million in net tangible book value it had agreed to maintain.

That month, with Fremont's stock in the cellar and its operations all but shuttered, the ratings agencies finally downgraded Fremont. They assigned the company's debt the ignominious status of junk.

Fremont filed for bankruptcy in 2008. As part of the proceedings, the California insurance commissioner sued to take control of the Ansel Adams photographs that had graced the company's headquarters for more than thirty years. When Christie's sold the prints at auction, they fetched $3.8 million.