The space shuttle Atlantis lifted off and disappeared into the sky Friday, and with it went NASA's longest running space travel program.

The final space shuttle voyage marks the bittersweet end of a 30-year era that will be remembered for its introduction of reusable spacecraft and the launch of the modern era of space exploration.

As Earth-orbit workhorses, the shuttles made it possible for the Hubble Space Telescope to continue giving us unparalleled views of the universe. Without the shuttle fleet, the International Space Station literally couldn't have been built.

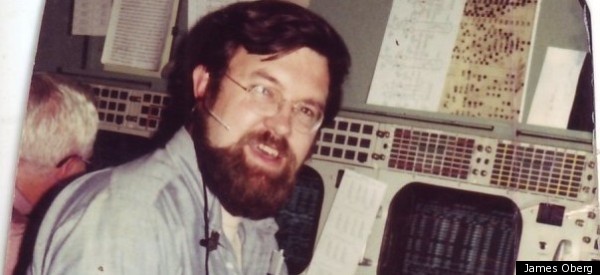

"I think the biggest lesson of the shuttle program is when you build a spaceship, you probably won't get what you were looking for, but you can almost always count on getting more of other stuff you hadn't expected," said former NASA rocket scientist James Oberg, who spent 22 years working on shuttle missions from 1975 to 1997.

Oberg was in Mission Control at the Johnson Space Center in Houston on April 12, 1981, for the very first shuttle launch. Designated STS-1, the Columbia shuttle spent just two days in space, orbiting Earth 37 times with its two-man crew of John W. Young and Robert L. Crippen. The main mission of that maiden flight was to make sure the shuttle could achieve orbit and return safely to Earth.

Oberg sat at one of hundreds of consoles with a specific job.

"I was watching the auxiliary propulsion system -- the steering and re-entry jets," he told The Huffington Post. "We were there to make sure the jets functioned properly, and if we saw something funny, we could get the crew to change the situation.

After working the first two shuttle missions, Oberg moved on to specialize in orbital rendezvous missions and is considered a pioneer in the development of space shuttle rendezvous techniques.

"Our team thought of ourselves as the heart surgeons of the flight control team," Oberg said. "We weren't involved with all the technical details of launching. We'd come in after the launch and control other aspects of the flight. I've worked about a dozen manned missions that were very intense and specialized."

Oberg led the team that designed the first space station assembly mission, and now works as an on-air consultant for NBC News. He said Friday's liftoff leaves him with mixed emotions.

"Well, I'm detached from the day-to-day, but I know many of my best friends and many people I've trained are facing career crises, because this kind of specialized work isn't widely practiced in the world," he said.

The New York Times estimates 7,000 layoffs are expected when Atlantis lands back on Earth.

"The next generation of spacecraft won't be flying for a number of years," Oberg added. "There's a gap because of budget limits. Most of the 6,000 jobs being lost in Florida at Cape Canaveral involve specific processing of shuttles that will not be needed again."

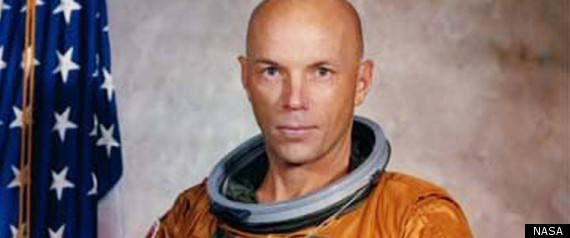

One former pioneering astronaut, Dr. Story Musgrave, echoed Oberg's sentiments.

"It's a matter of closure and triumph," Musgrave told The Huffington Post of the launch. "The shuttle did not turn out like we planned. It was going to [fly] 66 times a year and it ended up with about five times a year. It was going to cost $10 million a flight, and two months ago, an independent study showed that it cost $1.2 billion a flight. It was massively fragile, difficult to operate and exceedingly dangerous."

Musgrave served on six shuttle missions. Among his achievements is his work in developing the space suits used on all extra-vehicular space activities. In fact, he performed the very first shuttle spacewalk during the space shuttle Challenger's first flight in 1983.

Walking in space "feels the same as a ballerina on opening night at the ballet," he said. "I trained with Olympic figure-skating champion Dorothy Hamill. Indeed, spacewalking is like a choreographed athletic performance. I designed the spacesuit to flesh out its characteristics and its life support system, to see exactly what it could do."

Musgrave was also the lead space walker during the 1993 shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

When he wasn't orbiting Earth fulfilling important missions in space, Musgrave worked as a communicator in Mission Control during 25 flights, and he's grateful to have been part of the program.

"I look at us as a spacefaring nation," he said. "In 37 years, our state of the art, our maturity as space operators, has accelerated at a huge rate."

"If you look at who we were in '74 [when the U.S. completed the Skylab program -- the first space station] and who we are as a spacefaring nation and planet in 2011, we've come a long, long way. And the shuttle allowed us to do that," he said. "Even though at massive cost and danger, I still consider it a triumph -- it was a heck of a playing field for me."

Despite the disasters that claimed the lives of 14 astronauts on the Challenger and the Columbia, Oberg says it's cost -- not safety concerns -- that's bringing the space shuttle program to its end.

"It's not ending because it was more dangerous -- in fact, it's never been safer and the vehicles have never been in better shape," he said. But he said the space shuttle's "best abilities were no longer being utilized, simply as a freight and passenger hauler," concluding, "it really was far too expensive."

"It's like taking your Winnebago down to the corner just to get the newspaper," he said.

"It's a very logical, reasonable time," said Musgrave. "The shuttle's flown over 30 years and so I think it's a very reasonable time to decommission it, to call it a triumph and go forward."

PHOTOS FROM THE ATLANTIS LAUNCH: