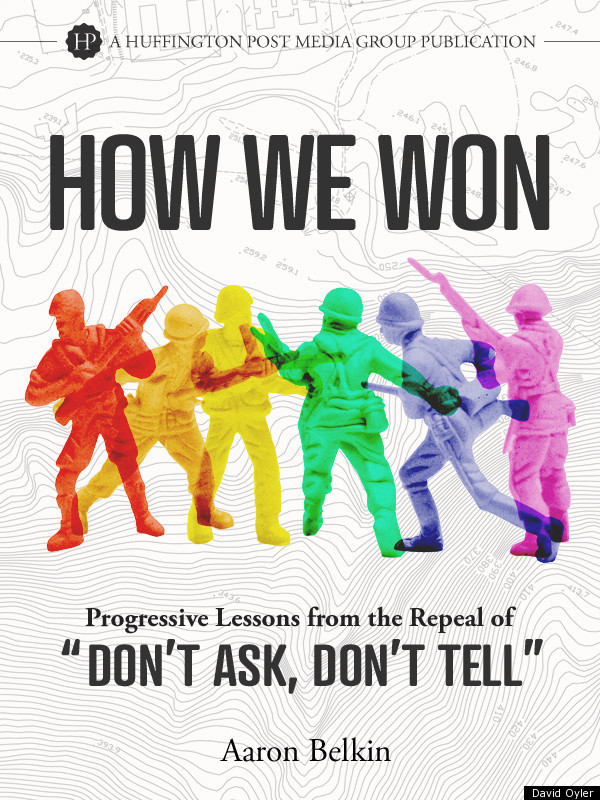

What follows is an excerpt from Aaron Belkin's "How We Won," a behind-the-scenes account of the strategies that helped overturn the ban on gays and lesbians serving in the military -- commonly known as "don't ask, don't tell." This book, part memoir, part analysis, is a compelling and informative primer on how Belkin, a scholar who labored for more than a decade in the repeal campaign, helped to change the minds -- and hearts -- of the American people and its Congress. For more on "How We Won," which is our second e-book, check out Arianna's blog post here.

CHAPTER ONE: David And Goliath

As a stoic looking Colin Powell testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee on April 29, 1993, he was flanked by the Service Chiefs, the top Army, Air Force and Marine Corps generals, and the Navy's top admiral. At issue was newly elected President Bill Clinton's proposal to change official policy to allow gay men and lesbians to serve openly in the military.

Powell, the most senior officer in the United States military, seemed almost apologetic as he explained why this would never work. He said that gay troops were good soldiers and loyal Americans who deserved our thanks. But, he went on, the military requires service members to live in confined settings where they have no privacy. Since gay Americans' lifestyle choices are neither accepted nor understood, introducing them openly into such intimate spaces would spread havoc within the ranks.

Powell was making an argument which would become known as the "unit cohesion rationale," the idea that allowing gay and lesbian troops to serve openly would dissolve the glue that makes teamwork possible. The key point is that straight troops don't like gays and cannot trust them with their lives. If gays were allowed to serve openly, then units would not develop the bonds of trust that have always held the military together. Powell explained to the senators that "cohesion is strengthened or weakened in the intimate living arrangements we force upon our people. Youngsters from different backgrounds must get along together despite their individual preferences. Behavior too far away from the norm undercuts the cohesion of the group."

During the 1993 congressional hearings that culminated in the passage of DADT, witness after witness, from the lowest-ranking enlisted personnel to the highest general, framed their testimony around this same argument. The unit cohesion rationale became the sledgehammer that crushed all outcries of unfairness and discrimination, because it didn't appear to be based on morality, homophobia, prejudice or intolerance. It was simply a matter of preserving the military's combat effectiveness. And who could be against that?

Several years later, in 1999, when a gay soldier was beaten to death with a baseball bat at Fort Campbell, Kentucky., former Marine Corps Commandant Carl Mundy published a New York Times op-ed in which he expressed regret over the soldier's death, and then pointed out that gay people and the military do not mix. "Conduct that is widely rejected by a majority of Americans," he wrote, "can undermine the trust that is essential to creating and maintaining the sense of unity that is critical to the success of a military organization operating under the very different and difficult demands of combat." Here was the unit cohesion rationale in action.

Because the Pentagon is supposed to be politically neutral, active duty generals and admirals tend not to use inflammatory language. But if you look at the rhetoric of retired military personnel, you can see that the unit cohesion rationale is really just window dressing for hatred, fears of AIDS, moral condemnation and graphic sexual imaginations.

Former Reagan Pentagon official, Ronald Ray, for example, published a book claiming that most gay men engage in extreme sexual practices, prey on children and spread sexually transmitted diseases. He referred to drinking urine and eating feces as "common homosexual practices," and he peppered his book with 352 footnotes to convey the impression that he had done scholarly research and that scientific data supported his claims.

Retired Lieutenant Colonel Robert Maginnis wrote The Homosexual Subculture, a paper that was entered into the Congressional Record, in which he claimed that gay bathhouses were "contaminated with fecal droppings because many homosexuals can't control themselves due to a condition called 'gay bowel syndrome.' They've exhausted their anal sphincter muscles by repeated acts of sodomy, thus becoming incontinent."

Although their published work was bogus, at least Ray and Maginnis were honest about their reasons for opposing gay troops. It wasn't concerns about unit cohesion that spurred them on. It was disgust and homophobia. These were the very same emotions behind the unit cohesion rationale, but the generals and admirals in charge of the Pentagon would never admit that in polite company. Hence their phony rhetoric about unit cohesion.

The military brass had a lot of company when it came to disliking gays, as intolerance was a central part of American culture in the early 1990s. When President Clinton nominated Roberta Achtenberg as an assistant secretary of housing in 1993, Senator Jesse Helms referred to her as a "damn lesbian ... a militant, activist, mean lesbian." Helms, who at one point tried to amend a bill to say that "the homosexual movement threatens the strength and survival of the American family," showed his Senate colleagues a video in which a shot of Achtenberg kissing her wife segued into a scene of a man dressed as a Boy Scout sodomizing Uncle Sam. With great pride, Helms announced, "I'm not going to put a lesbian in a position like that. ... If you want to call me a bigot, fine." This prompted Senator Robert Smith, a conservative Republican from New Hampshire, to claim that Achtenberg was "one who, if she had her way, would shut down all the Boy Scout troops in America and replace them with sex clubs festering with disease."

The Achtenberg hearings even evoked intolerance in more moderate politicians. Senator Alan Simpson from Wyoming, who would later become an ally of the gay community, implied that gay people were not part of the American family, that they belonged to the category of the stranger or the alien. And Senator Joe Lieberman, the Connecticut Democrat who would also become an advocate of gay rights, unabashedly announced that he did not personally approve of the "homosexual lifestyle."

Despite the somewhat more muted rhetoric in the gays-in-the-military debate, the homophobic sentiment in Congress was overwhelming. After all, both Congress and top military brass knew at the time that the unit cohesion rationale was a lie. How can we be sure? In an unsuccessful effort to ensure that public policy would be based on rationality and evidence, the Clinton administration asked the RAND Corporation to do a study in 1993 on whether or not letting gays and lesbians serve openly would harm the military. Founded by the Air Force, RAND is one of the most prominent think tanks in the country, and it has a long history of producing respected, military research. RAND's 518-page study was co-produced by dozens of scholars and cost taxpayers $1.3 million dollars. Its conclusion: No harm would be done by letting gay men and lesbians serve openly.

At the same time, a small group of Pentagon brass, known as the "Military Working Group," released a report on the very same question. The Working Group's so-called study was 15 pages long, included no actual data, and was signed by five generals and admirals -- but no scholars. In histrionic prose, the "study" depicted gay people in a vicious and grotesquely sexualized way. It demonized them and suggested that they were perverts who had no place in a community of warriors.

Congress reviewed both studies and decided to ignore RAND and endorse the Military Working Group. The result was the passage of DADT into law.

The new statute would include fifteen "findings" which spelled out each step of the unit cohesion argument, one by one. The money line in the statute was the fifteenth finding: "The presence in the armed forces of persons who demonstrate a propensity or intent to engage in homosexual acts would create an unacceptable risk to the high standards of morale, good order and discipline, and unit cohesion that are the essence of military capability."

When Congress passed DADT into law in 1993, the obstacles to gay equality in the military seemed to loom up like an indomitable giant, sending the gay community into despair. We could cry foul as long and as loudly as we wanted, but while the Pentagon brass kept insisting that gay troops would hurt the military, it would remain impossible to achieve any meaningful political progress. And there was no apparent way to convince the generals to change their tune because of the degree of homophobia and vitriol just below the surface of everything they said.

I was in graduate school in 1993, and wouldn't enter the fight against DADT until 1999, when I founded the Palm Center, an institute dedicated to making sure that public policy was based on solid research rather than distortion. What followed was 11 years of hard work conducting scholarly research and then disseminating that research to the public.

My central argument in this book is that, in order for Congress to repeal DADT, political and military leaders, as well as the public at large, had to be convinced that allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly would not harm the military. This single idea was the main roadblock to political progress, the obstacle we had to overcome to make it safe for politicians to repeal DADT. It didn't matter that scholars already knew that the Pentagon wasn't telling the truth. The key was to get the American people to understand.

It was difficult to convince the public that esteemed military brass could not be trusted, and in the chapters that follow, I explain the five strategies that my fellow scholars and I used to persuade citizens and leaders. These strategies worked well. By the time Congress voted to authorize the repeal of DADT in late 2010, those who persisted in arguing that gays harm the military were in a tiny minority. Their assertions about DADT had been consistently countered by more than a decade of research. Not only did they fail to win support, they seemed unhinged and out of touch.

Perhaps most importantly, the implications of our academic research and public education campaign extend far beyond DADT repeal, because the strategies we used to persuade the public to change its mind upend some of the left's most cherished conventional wisdom about how to prevail in politics. Recent defeats on taxes and the debt ceiling have left many progressives in despair, and there is no doubt that these have been dark days for the left. But when the LGBT community launched the campaign to change the public's mind, we faced obstacles that were as formidable as those that stand in the way of today's broader progressive community. And we won! Progressives working on other issues could benefit from the lessons that emerged from the struggle to repeal DADT, and could harness our strategic approach to great effect.

Like this book? Buy it now →