Michael Klink, a 59-year-old civil engineer from Auburn, In., says he reported a litany of problems when he was working as a construction inspector at several pumping stations along the Keystone oil pipeline as it was being built in 2009 -- from sloppy concrete jobs and poorly spaced rebar to bad welds and poor pressure testing.

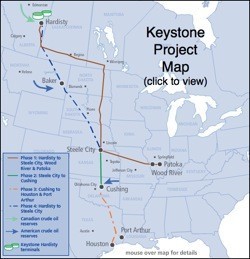

For his diligence, Klink says, he was harassed, berated and ultimately fired. The experience has left him convinced that a controversial proposal to expand the Keystone pipeline matrix, which would ultimately deliver as much as 1.3 million barrels of crude oil a day from an oil patch in Alberta, Canada, to refineries in the Midwest and the Texas Gulf Coast, should never gain federal or public support.

"They didn't care, and that's why you've seen all these leaks already," Klink said. "And I worry that it's only a matter of time before there will be another disaster like the Deepwater Horizon -- only this time it won't be out on the water. It will be right in the middle of the country.

"I'm no treehugger," Klink added. "I just think things ought to be built right, and I have no faith that these guys can do it."

Evidence supporting his skepticism isn't hard to find. In just over a year of operation, the Keystone network's existing leg, which runs through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri before terminating in Illinois -- has leaked more than a dozen times. In most cases, the amount was small, and federal officials have suggested that such hiccups are common to new pipelines. But two incidents in May, including one that spewed more than 20,000 gallons of oil, prompted regulators to briefly block Keystone from moving oil in June. Virtually all of the spills happened at pumping stations like the ones where Klink worked.

"I feel for the people living alongside that pipeline," he said.

Klink's concerns emerge against a backdrop of increasingly bitter debate over Keystone. The Federal State Department, which is responsible for issuing permits for pipelines crossing international boundaries, has already conducted two environmental assessments of the Keystone expansion proposal, known as Keystone XL, concluding both times that the impact would be negligible. This week, State Department officials are on a listening tour in the six states -- Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas -- through which the pipeline is expected to pass.

The project has drawn increasingly vocal opposition from environmentalists and clean-energy advocates, who argue that it would spur wanton development of Canada's oil sands, also known as tar sands -- an unconventional source of crude oil that requires vast amounts of energy and produces substantial amounts of greenhouse gases during processing. They also worry that the proposed expansion route would take the pipeline directly through a large portion of the Ogallala Aquifer, which provides as much as 30 percent of the nation's ground water used for irrigation, as well as drinking water for a wide swath of the American heartland.

Even so, in at least one previous public statement, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has indicated that she is inclined to approve the pipeline, to the delight not just of TransCanada, the Calgary-based company behind the Keystone network, but to supporters on both sides of the border who argue that the environmental concerns are vastly overstated and that Canada's oil sands will be tapped whether or not the Keystone expansion is built. They also say the pipeline represents tens of thousands of potential jobs, and that it provides an important stepping stone on the road to American energy security.

As for the leaks on the existing leg of Keystone, a spokesman for TransCanada, Terry Cunha, said they were mostly attributable to a bad batch of metal fittings, and that the company has since made the necessary repairs. "We take the safety of our system very seriously," he said.

Klink says he's not so sure. He filed a complaint with the Department of Labor last year, under whistleblower provisions of the Pipeline Safety Improvement Act of 2002. His case is still pending.

In its final environmental impact statement for the Keystone expansion, which was issued at the end of last month, the State Department cites the federal body that oversees pipeline safety in the U.S., the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, in concluding that the spills that have plagued the first leg of the network are essentially "start-up issues that occur on pipelines and are not unique."

Anthony Swift, an attorney with the Natural Resource Defense Council's International Program in Washington who has testified before Congress about the Keystone network, says that's not entirely true. "For a new pipeline it's very unusual," he said. "Keystone is the newest pipeline in the U.S. to be given a corrective action order."

That order came in early June, after incidents on May 7 at the Ludden pump station in Brampton, N.D., where between 450 and 500 barrels were released after a "pipe nipple failure," and then on May 29 at the Severance pump station in Bendana, Kan., where about 10 barrels were lost. PHMSA's corrective action blocked TransCanada from resuming use of the pipeline after the second incident. That block was lifted the following day, after the company satisfied the federal agency's call for metallurgical tests on the pipes involved.

Cunha said these -- and the majority of other incidents over the pipeline's year-long operating history -- were attributable to a variety of pipe fittings that had some weaknesses. All of these, he said, have been replaced -- as have other pipe fittings at sites where no leaks were detected, out of an abundance of caution. "Unfortunately you may get 1,000 fittings and 999 will work as designed," he said. "But unfortunately, sometimes one fails. We work really hard with our suppliers to make sure we get really good equipment."

Klink says he pointed out repeatedly that the metal piping being deployed at the pump stations he inspected was of inferior quality, and that the impurities were making it difficult for welds to properly hold. His complaints, he said, were often rebuffed. He also suggested that any equipment, no matter the quality, is only as good as the people installing it, and he's convinced that other problems loom on the horizon.

The pumping stations themselves are large facilities -- a bit under an acre in size -- situated at 50 mile intervals along the Keystone conduit. Crude-carrying pipeline comes up out of the ground and into each facility, where the pressure is boosted by multiple 1,000-horsepower motors, sending the oil hurtling further down the line.

In March 2009, Bechtel made Klink a temporary inspector in North Dakota. TransCanada had contracted with the oil and gas services giant to supervise work performed by yet another company, TIC of Wyoming. Friction between the TIC construction crew and Bechtel inspectors was an issue even before Klink arrived, according to Klink's complaint with the Department of Labor.

In 2008, for example, a TIC crew member assaulted a Bechtel inspector, spitting tobacco at him and knocking him down, according to the filing. "Although that individual was later terminated," the document notes, "the attitudes of TIC employees did not change."

In an interview, Klink recalled other incidents. At the Niagara pump station site, just west of Grand Forks, N.D., for example, he says he came under pressure from his own supervisors to fudge tests designed to ensure that the soil underlying the facility was compacted properly. He did that, instructing the test takers, armed with nuclear density meters, to take four or five measurements near the driveway leading into the site where the soil was hardest. That was considered sufficient, Klink says, even though the larger part of the site never got a sufficient density reading. In his estimation, it never would have.

In an interview, Klink recalled other incidents. At the Niagara pump station site, just west of Grand Forks, N.D., for example, he says he came under pressure from his own supervisors to fudge tests designed to ensure that the soil underlying the facility was compacted properly. He did that, instructing the test takers, armed with nuclear density meters, to take four or five measurements near the driveway leading into the site where the soil was hardest. That was considered sufficient, Klink says, even though the larger part of the site never got a sufficient density reading. In his estimation, it never would have.

"It was too sandy," Klink said. "They were never going to get good readings."

Klink says he now worries that the foundation could slowly settle unevenly, causing pipes to twist.

In other cases, he said -- particularly at the Edinburgh station just a few miles shy of the Canadian border in North Dakota, as well as at other sites -- steel rebar used to reinforce the poured concrete foundations was installed haphazardly, ignoring the engineering specifications that would necessarily anticipate supporting the giant, multi-ton motors, bolted to the concrete, and torquing in specific ways.

Klink says he watched workers use blow-torches to bend and reshape uncooperative pieces of rebar that didn't align. "That compromises the strength of the rebar and the integrity of the design," he said. "You're not supposed to do that. Sometimes, if a rebar wouldn't match up right, I've even seen them take a torch and cut a chunk out so it would work."

In some cases, Klink said, he'd call attention to these problems, and after some tussling, it would be redone. In many others, he said, he'd meet stiff resistance from TIC workers, and get no support from his Bechtel superiors. Sometimes, he said, foundations would be poured before he even had a chance to sign off on the underlying work.

According to the federal inventory of Keystone's leaks, many of the problems were attributed to seal failures. Klink said he's not surprised, saying that the contractor was using improper equipment and techniques to get sections of pipes and pumps to line up. In one case, he said he witnessed workers using industrial-strength cables and ratchets to heave huge sections of pipe and pump into alignment so they could be joined -- a recipe, he said, for stress failures down the line.

Both Bechtel and TIC, Klink added, were chiefly concerned with getting the stations to pass basic pressure tests so they could close the job and move on, without ensuring that the complex matrix of seams, welds and pipes would last over time.

In one instance, he recalled a conference call in which a Bechtel employee reported that the Edinburgh site "hadn't leaked too much" when passing its pressure test.

"Well, shit, that thing shouldn't have been leaking at all," said Klink, who also insists that he was the only inspector he knew on the project who actually held an engineering degree. "This whole process is really very much a science -- unless you're going to do it all haphazardly because you figure you're out in the middle of nowhere."

In late April or early May, according to Klink's filed complaint, perhaps prompted by complaints from Klink and others about conflicts among the various contractors and inspectors at the northern end of the pipeline, Bechtel dispatched a quality assurance supervisor to the Dakotas to investigate.

Klink was interviewed at length, as were other inspectors, construction workers and supervisors, and a report was prepared for Bechtel executives. Klink said he was never made privy to the findings, but in late May, he was reassigned to South Dakota.

His transfer papers indicated an end date of Dec. 31 for the assignment, but as he continued to report similar problems at pump stations there, tensions with his Bechtel supervisors increased, and on Sept. 23, 2009, he was told he was no longer needed. On the same day, he learned that federal inspectors were planning to make their first visit to Keystone construction sites the following week.

He was never hired back, despite myriad openings for inspectors on the ongoing project. He also has been unable to find work anywhere else, suspecting that Bechtel portrays him as a "problem inspector" with potential new employers.

"Maybe I'm just stupid," says Klink, whose accounts were confirmed by one other former Bechtel employee, who asked that his name not be used because he feared a similar fate in the industry. "Maybe I should have just kept my mouth shut. This is just a total disaster of a lifetime. But I believe in doing things correctly, and not half assed and calling it good enough. That is one thing that's wrong in our country -- close is good enough."

Representatives of TIC did not return emails or phone calls for comment on this article. Officials with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration also did not respond to queries for comment on its oversight of the Keystone project.

Michelle Michael, a spokeswoman for Bechtel, said that out of respect for the ongoing investigation of this case with the Department of Labor, the company would not comment on the particulars of Klink's employment or his allegations.

In an email message, however, she said "the fundamental responsibility of Bechtel's inspection team, including Mr. Klink, was to strictly enforce the rigorous quality control standards that Bechtel implements on all of its projects. Mr. Klink's job was to raise any concerns about contractors' performance," Michael continued. "When he raised concerns, they were taken seriously and appropriately addressed, including the issues related to the behavior of contractors' personnel."

She added that Klink was not the subject of any retaliatory practice, and that his assignment ended when the project phase he was assigned to was completed -- "as is common in the construction industry," she said.

Shawn Howard, a TransCanada spokesman, said that his company is always made aware when questions or concerns are raised by inspectors during construction. "We use multiple quality-control and inspection processes during the manufacturing and construction stages," Howard said. "If a concern is raised we investigate immediately. If corrective action is required, we act -- and there is no issue with the Keystone pipeline."

He added that Klink's complaint does not suggest that TransCanada failed to act or that any issues still exist. "Again, there is no issue with the Keystone pipeline," he said.

But Klink says that's already been demonstrated to be false, and that he's hoping lawmakers in Congress will allow him to share more details of his story with them, and perhaps help block approval of the Keystone expansion to the Gulf. He said he'd even be willing to take a lie detector test, if it came to that.

"I believe I was wronged and I believe that people have to stand up for what is right," Klink said. "And I feel like I'm standing up for people -- for the farmers and everybody up and down that pipeline in North and South Dakota.

"It's going to cause another oil disaster and harm innocent people who didn't deserve it," he added, "and they may never recover from it."