Education Management Corp. was already a swiftly growing player in the lucrative world of for-profit higher education, with annual revenues topping $1 billion, but it had its sights set on industry domination. So, five years ago, the Pittsburgh company's executives agreed to sell its portfolio of more than 70 colleges to a trio of investment partnerships for $3.4 billion, securing the needed capital for an aggressive national expansion.

One of the new partners brought an outsized reputation for market savvy, deep pockets and a relentless pursuit of profits -- the Wall Street goliath, Goldman Sachs.

After the deal closed and Goldman became a partner, employees soon noticed a drastic shift in culture. Longtime admissions managers were replaced, ushering in an era in which recruiters were endlessly hounded by supervisors about hitting weekly enrollment targets. The admissions staff nearly tripled, requiring expanded floor space to accommodate a sales force of more than 2,600 across the country.

Management handed down revamped telemarketing scripts designed to prey on poor and uneducated consumers, honing in on their past mistakes in life as a ploy to convince them that college would solve all their problems, according to conversations with more than a dozen current and former Education Management Corp. employees over the past two months.

"You'd probe to find a weakness," said Brian Klein, a former admissions employee who worked for three years at Argosy University Online, one of four major colleges operated by EDMC. "You basically take all that failure and all those bad decisions, and you spin it around and put it right back in their face as guilt, to go to this shitty university and run up all of this debt."

Just as the subprime mortgage bubble was giving way to a bust that would help trigger a devastating financial crisis, Goldman Sachs, a firm that had been at the center of Wall Street's rampant mortgage speculation, found its way to a new area of explosive growth: In claiming what would eventually become a 41 percent stake in Education Management Corp., Goldman secured itself a means of tapping into the boom in for-profit higher education. The federal government was boosting aid to college students nationwide, just as a declining economy prompted millions of Americans to seek refuge in higher education, leading to dramatically expanding enrollments at many institutions.

But unlike in the mortgage markets, where some unwise or unlucky investor got saddled with the bad loans after the festivities ended and home prices fell, this new market in higher education boasted seemingly unlimited growth potential at virtually zero risk. The burden of college loan repayment falls entirely on students' backs, shielding corporations from the consequences of default. The colleges essentially receive all their revenues upfront, primarily through federal government loans and grants for tuition, regardless of whether students are able to gain employment and pay back their loans.

Soon after the Goldman buyout, the newly private Education Management LLC embarked on its most ambitious period of growth -- one that has recently brought it crosswise with federal prosecutors, who have accused the company of widespread fraud in its recruitment processes.

The timing for expansion had been ideal: With the help of current House Speaker John Boehner, Congress in February 2006 deregulated the world of online learning, opening a significant frontier to colleges seeking to expand their enrollments. A month after the online learning law took effect, in March, EDMC's board of directors announced the acquisition by Goldman and its partners.

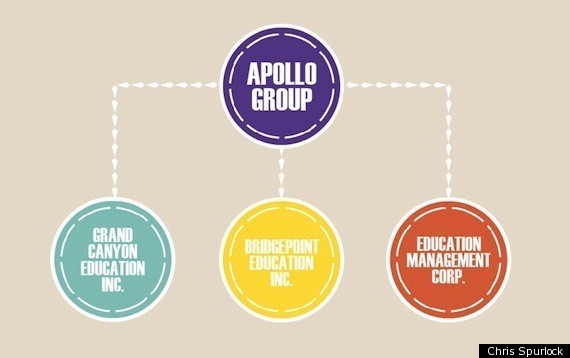

The company's newly installed board, which included representatives from Goldman Sachs and the other private equity investors, sought a new team of executives to run the operations. They drew from the ranks of EDMC's biggest competitor, the University of Phoenix. Chief among those new recruits was Todd S. Nelson, the longtime former chairman and chief executive of Phoenix's parent company, the Apollo Group.

Under Nelson, the University of Phoenix had become the unquestionable star of the for-profit higher education world, boasting more than 300,000 students and revenues topping $2.4 billion in 2006 -- triple the revenues from five years earlier. But he left abruptly in 2006, after signing a $9.8 million settlement with the Department of Education over allegations of widespread recruiting violations at the school -- allegations that have now resurfaced at EDMC.

Revenues grew swiftly at EDMC after the company was taken private in 2006

Under Nelson's new leadership, enrollment and profits at EDMC skyrocketed further. The number of online recruits in particular grew at an astronomical rate, increasing fivefold between 2006 and 2009, after deregulation allowed the company's classrooms to become completely virtual. By late 2009 the company tapped Wall Street again, with an initial public offering that netted more than $330 million.

But a recent complaint from the U.S. Justice Department detailed a business bent on recruiting students at all costs, a description supported by the accounts of the employees interviewed by the Huffington Post. Hidden behind the upbeat earnings calls and bullish quarterly reports was a cutthroat sales culture that rewarded employees who regularly bent the truth and took advantage of underprivileged and unsuspecting consumers, employees said.

Goldman Sachs and Providence Equity Partners, the other major private equity player in the deal, declined to comment for this article.

According to a statement from EDMC, "the company's focus on the student experience and success did not change after the 2006 transaction." The statement noted that EDMC has doubled expenditures on capital improvements intended to benefit students in the five years after the private equity deal.

But employees recounted a distinct culture shift once the company went private under Goldman Sachs and the other private equity investors, as day-to-day operations warped from a commitment to students and their success into an environment laser-focused on hitting mandated enrollment targets. New recruits were viewed simply as a conduit for federal student assistance dollars, the employees said, and pressure mounted from management to enroll anyone at any cost.

A vanity plate for an admissions director at EDMC's Online Higher Education Division in Phoenix. Photo credit: EDMC online admissions employee

Recruiters told people with felony criminal records that pursuing a criminal justice degree would allow them to achieve their dreams of joining the FBI -- an impossible scenario, because the bureau is barred from hiring people who have been convicted of such offenses. They convinced students with no access to a computer or Internet that they could use the local library for classes, even though they would need to save files and download specific software to access coursework.

"It just got to the point where I felt like I was lying to these people on a regular basis," said Patrick Flynn, a recruiter at EDMC's South University online from 2006 through 2009, when he quit. "Honestly, I just felt dirty doing the things I was doing. It's almost like they were trying to make me take advantage of people's belief in what this education was going to get them, when I didn't buy into it myself."

EXPONENTIAL GROWTH

Education Management Corp. had grown from humble roots, getting on the map by purchasing the Art Institute of Pittsburgh in 1970. After EDMC went public the first time in 1996, the company expanded rapidly by acquiring other accredited colleges and trade schools -- a common growth strategy in the for-profit higher education industry. Between 2001 and 2006, the company bought more than three dozen new colleges across the country, ranging from culinary schools to traditional four-year liberal arts colleges.

By the time Goldman and the seasoned team of University of Phoenix executives arrived in 2006 and 2007, EDMC was already a juggernaut. It owned more than 70 college campuses across the country and had doubled its revenues over the previous five years. During that timeframe, its student population tripled to more than 72,000 -- larger than mammoth state universities such as Ohio State and the University of Texas.

But the Goldman investment promised to propel the company to even greater heights. Like many companies in 2006, Education Management Corp. was attracted to private equity as a way to realign the company and maximize future profits. Easy credit before the financial crisis made 2006 a record year for corporate buyouts.

"Taking the company private will provide us with patient capital and a long-term strategic horizon," then-chief executive John "Jock" McKernan Jr., a former Maine governor and congressman who is married to Sen. Olympia Snowe (R-Maine), told investors on a conference call in 2006. "It will allow us to accelerate our strategies to expand our traditional and online program offerings and also give us an opportunity to enter additional new geographic markets."

For the new investors, 2006 opened a particularly attractive opportunity to invest in higher education. After years of lobbying by the for-profit college industry, John Boehner, then the chairman of the House education committee, helped to eliminate a key provision that had moderated the growth of exclusively online universities.

The so-called 50 percent rule, which required half of all students to be at a ground campus in order for a school to be eligible for federal aid, had been put in place to discourage dubious distance education programs that offered subpar learning. Boehner helped to nix the rule in a budget agreement that took effect in early 2006, allowing schools to expand enrollments -- and revenues -- without having to invest in additional ground campuses. A spokesman for Boehner did not respond to requests for comment.

"When Goldman shows up at the party, they show up as the smartest guys in the room," said Barmak Nassirian, who followed EDMC's rise over the past decade as the associate executive director of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. "2006 was the significant year, because that was the year that the smartest people figured out how easy it was going to be to grow geometrically. You'd have to be from Mars not to know that they were smelling an easy path to big bucks."

The EDMC investment promised a window into the virtually risk-free world of government-guaranteed student lending, much in the way that Goldman's acquisition of Litton Loan Servicing in 2007 gave the investment bank a channel into the once-fruitful subprime mortgage servicing business -- a sector that has since been branded predatory.

Likewise, consumer and student advocacy groups have long argued that the incentives are skewed for corporations that rely on student loan money, as the most punitive burdens from the government fall on students. The government over the past decade has tightened restrictions on federal student loans, making them nearly impossible to discharge, even in bankruptcy.

"There's been a transfer of risk," said Deanne Loonin, director of the National Consumer Law Center's Student Loan Borrower Assistance Project. "It's less risky for the schools and much much more risky for the students, with no safety net."

When the three private equity firms purchased all of EDMC's outstanding stock in 2006, it came at a premium. The $3.4 billion transaction was priced at $43 per share, more than 25 percent higher than the company's stock price over the prior six weeks.

The company's filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission at the time laid out some of the attractive aspects of investing in higher education: "Given the advanced payment of tuition and fees which is customary for the post-secondary education industry, our working capital is on average a source of cash," the filings argued. The expansion of online programs also offered "an attractive avenue for growth that utilizes many of our existing education curricula while requiring less capital expenditures relative to campus-based expansion."

Student enrollments at EDMC nearly doubled after 2006, and online-only enrollments grew swiftly

"At the time, the company had just an emerging online component, and we wanted to help the company invest in developing online programs," said Jeffrey Leeds, a current EDMC board member and the president of Leeds Equity Partners, who said he came up with the original idea to take EDMC private and brought it to Goldman Sachs and Providence Equity Partners. "Quite simply, we are believers in the need for higher education to continue to innovate and change the model."

Though the school had nearly 80,000 students by the time Goldman and the other private equity investors took over, only about 4,000 of those students were enrolled in online programs.

The company needed a new leader to expand the fledgling online operation.

They found one in Todd S. Nelson, a man who brought two decades of experience at the nation's largest private college system, 2,000 miles away in Arizona.

PHOENIX RISING

Nelson began his career in the for-profit education sector in 1987, when he became the director of the University of Phoenix's Utah campus. He swiftly rose through the ranks, becoming the Phoenix system's executive vice president in 1989 and president of Phoenix's parent company, the Apollo Group, in 1998. Three years later, he became chief executive of the company. And three years after that, in 2004, Nelson was named chairman of the board. It was the first time in the company's 28-year history that someone other than John G. Sperling, the University of Phoenix's eccentric founder, had served as chairman.

During Nelson's term at the helm of the Apollo Group, the operation thrived, becoming the largest private higher education institution in the nation. Student enrollment grew from 71,000 to more than 200,000 between 1998 and 2003. Online enrollments rose tenfold, from 7,200 to 79,000, during the same period.

The company became a darling on Wall Street. Share prices rose from $10.57 in 1997 to more than $63 per share in 2003. Revenues jumped nearly fivefold from 1997 to 2003, topping $1.3 billion.

A 2002 corporate goal known as "5-5-5" summed up the Apollo Group's aspirations for growth under Nelson: "Five Years, Five Million Students and Five Billion Dollars," according to a Department of Education report on Phoenix from 2004.

But along the way, the company's lightning-fast growth was attracting the attention of federal regulators at the Department of Education. In a report made public in 2004, the department described the University of Phoenix as a predatory machine, with a sales force that was singularly focused on maximizing enrollment numbers.

Recruiter salaries could range anywhere from $26,000 a year to $120,000. Managers enticed employees with brochures about the money they could make by enrolling the most students. One of the brochures had bullet points that read, "$$$ - No limit on income," "Highest paid people in the world are salespeople" and "Top 20 % = Never worry about $$$."

White boards displayed around the office tracked each recruiter's performance, and managers sent daily barrages of emails questioning why enrollment targets weren't being met.

High-performing recruiters could be eligible for the "Sperling Club Trip Awards," named after the University of Phoenix founder, which were all-expenses-paid trips to destinations such as Universal Studios, Washington, D.C., or San Francisco.

Recruiters who failed to meet enrollment targets were humiliated and intimidated by managers, according to federal investigators. Low performers were moved to a glass-enclosed office known as the "red room," according to the Department of Education report, where they were easily visible to the rest of the office. Managers "hovered" over recruiters in the red room and closely monitored their calls.

"Those who were sent to the red room were allowed no vacation time and were allowed no breaks other than those specifically set for those working there," according to the report.

Among the most important findings in the University of Phoenix report were the consistent accounts from both recruiters and enrollment managers about how employees received raises. Central to the salary calculations was a performance chart known as "the matrix," which clearly laid out how many students were needed to attain certain salary brackets.

Paying incentives to college admissions recruiters has been a problem plaguing the for-profit college industry for decades. Dating back to the early 1990s, Congress passed consumer protection rules that banned schools from creating any commission, bonus or other incentive payment "based directly or indirectly on success in securing enrollments or financial aid to any persons or entities engaged in any student recruiting or admission activities."

But the Bush administration relaxed those rules in 2002, stating that it was not Congress' intent to completely prohibit merit raises. At the time, the top Department of Education official overseeing higher education was Sally Stroup, who had previously worked as a lobbyist for the Apollo Group.

Under Stroup, the Department of Education added a series of "safe harbors" to the rules governing commissions, adding language that salaries could be adjusted twice a year as long as they were "not based solely on the number of students recruited, admitted, enrolled, or awarded financial aid."

A spokeswoman for Stroup's current employer, Scantron Corp., said she was unavailable for comment.

Numerous critics at the time argued that the addition of the word "solely" gave schools far too much leeway to entice their recruiters. A number of admissions salespeople and managers at the University of Phoenix told Department of Education investigators that enrollment numbers were the only performance measure anyone cared about.

The other criteria, such as "customer service," "communication" and "judgment", were simply "smoke and mirrors" and "smokescreens" meant as "a way to deceive the Department (of Education)", according to recruiters interviewed in the report.

A timeline of events at Education Management Corp.

Before the report was made public in September 2004, University of Phoenix had already agreed to a $9.8 million settlement with the government, in which the school admitted no wrongdoing. Nelson told the Arizona Republic at the time that the report was "very, very unfair."

Even with that taint, Nelson's tenure could be logged as a substantial success in terms of what he delivered to shareholders. Up against the company's earnings, the federal settlement payout looked like small beer.

"Look at how much he brought in," said Nassirian, of the Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. "Ten million dollars was less than they paid in bonuses that year. What they care about is return on investment. In the scheme of things, this is a successful executive."

Nelson remained with the company until January 2006, when he abruptly resigned, sending shareholders into a panic that drove Apollo Group's stock down nearly 20 percent from a few months before. The departure came after Apollo had to revise earnings projections downward in recent months, amid slowing student enrollment.

As a condition of his departure, Nelson could not work for a competing education company for a year.

FRESH LEADERSHIP, OLD SCRIPT

The year during which Nelson was forced to stay clear of the industry came with some consolation: He left with a generous $18 million severance package from the Apollo Group, according to a separation agreement filed with the Securitites and Exchange Commission.

In 2007, Fortune magazine named Nelson one of America's 25 highest-paid men. His combined compensation and severance pay from the Apollo Group totaled $41.3 million, putting him just ahead of Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase's president and chief executive.

A year after leaving the University of Phoenix, he reemerged to take the reins at Education Management Corp.

By early 2007, EDMC was already a substantially changed company compared to its pre-buyout days. Except for McKernan, the former Maine governor and congressman who had served as chief executive prior to Nelson, an entirely new board of directors was in place, including a representative from Goldman Sachs and two from Providence Equity Partners.

"EDMC was a large company, and Todd obviously had experience running a large company in the for-profit college space," said Leeds, the current EDMC board member who headed one of the investment firms that bought out the company. "We thought, as we transitioned, that it made a lot of sense to bring in more talent. That's what companies always do."

Many executives in for-profit higher education got their start at the Apollo Group. Click here to see an interactive graphic

After Nelson joined the company in February 2007, the board recruited more Apollo Group executives later that year, including Robert A. Carroll, the longtime chief information officer at Apollo, and Craig Swenson, who came on as senior vice president after working in the same capacity at University of Phoenix.

Soon after, according to employees, some of the very same practices documented at the University of Phoenix began to resurface on the sales floors of EDMC.

Managers erected dry-erase boards to publicly track enrollments. Admissions directors began sending emails at a furious pace, tracking enrollments daily and even hourly. Admissions directors circulated statistical reports to management tracking each recruiter's enrollment statistics.

A November 2009 email from April Cumpston, a director of admissions at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh's online division, obtained by The Huffington Post, gives a sense of the pressure to enroll students.

She wrote to her team: "We aren't holding up our end of the bargain. We need to engage EVERYONE who picks up the phone and STOP SETTING APPOINTMENTS. Why are we letting them off of the phone? Are we making them push us off 3 TIMES?? We have proven that we can close the students we talk to but we need to talk to more students!!!!"

Employees who had worked at the company prior to Nelson's arrival noticed a distinct shift once he came on board.

"It was an absolute feeding frenzy," said Kathie Bittel, who worked as a recruiter at Argosy University the first year after the company went private under Goldman, when Nelson came on board. "They were on us every minute of the day. We had managers and directors who were just literally circling the pods, listening to every word that was spoken. I swear I thought they were going to wear out the carpeting."

According to an account in a 2010 federal court filing, a former vice president for marketing and admissions operations who worked at EDMC from 1988 until 2010 noted that once the investors took over in 2006, "EDMC's focus changed as the 'new group managed it short term' to consider its 'financial interests.' "

The same witness also attested that EDMC's new management, including Nelson, "criticized EDMC's historical business practices, including that EDMC had 'not grown fast enough,' and was 'too cautious' and 'not aggressive enough.' "

Jeff Abraham, a former vice president for marketing and admissions operations at EDMC during those years, matches the description of the confidential witness, according to his publicly accessible profile on the social networking site LinkedIn. Reached by email, Abraham would neither confirm nor deny that he was the confidential witness, though he said he has at various times spoken to "several attorneys representing different parties."

The lawsuit -- which was brought on behalf of EDMC shareholders who lost money when the company's stock plummeted -- was recently dismissed on narrow grounds: A federal judge ruled that plaintiffs had failed to prove that EDMC had deliberately misled shareholders about its internal operations.

Former employees described the pressure ramping up on the sales floor after Goldman and its partners entered the business, leading to an atmosphere where "no" was not an acceptable answer.

"When I first started working there, people legitimately felt like it was about the student," said Flynn, the recruiter at South University who arrived in fall 2006, just a few months after the company went private and a few months before Nelson took over as chief executive. "If you had an explanation of why a student wouldn't enroll right away, it was listened to. But then it became more about, 'you need to get that person to enroll, and you need to overcome their objections.'"

Leeds, the current EDMC board member and original private equity investor, dismissed the suggestion that the culture changed at EDMC after the company went private and Nelson came on board.

"This notion that somehow private equity folks acquired the company and changed the culture and turned it into a boiler-room mentality is just nonsense," Leeds said. "We're people who take this stuff really seriously. We have two former secretaries of education on my board of advisers. Do you think they would be associated with people who would ever think about or be capable of creating a boiler room? It's nuts."

EDMC also disputed the idea that a change in ownership shifted any priorities for the company.

"The Company's focus has always been on student success, including under Mr. Nelson's leadership," a spokeswoman said in a prepared statement. "Certainly, the Company does not condone unethical recruitment practices. If any such activity were brought to our attention of our organization, immediate corrective action (up to and including termination of violating employee) would be taken, as per our Code of Business Ethics and Conduct."

But more than a dozen employees interviewed by The Huffington Post said the imperative to enroll students through whatever means available became a central focus of the sales culture at EDMC.

An internal instructional brochure for admissions officers, obtained by The Huffington Post, described typical excuses cited by admissions employees for failing to enroll a potential students and forbade them from accepting any of them.

"My student's dog died, her cousin is graduating and she just got pregnant," began a hypothetical excuse from one recruiter.

The instructional brochure instructed that director not to accept those reasons. "You are missing something!" the brochure declared, urging recruiters to press harder. "Build rapport, trust, and relationships with your student that they feel comfortable telling you concerns and why they are scared."

Another script illustrated management's desire for recruiters to employ relentless efforts to keep students on the phone for sales pitches, dismissing potential reasons why a conversation might not be convenient at that moment.

"I'm at work right now," read one hypothetical response, with the recruiter instructed to reply, "I understand many of my students are working professionals. What type of work are you in?"

"I'm running out the door," read another. The recruiter's response: "I understand, I can appreciate that you are busy! What I wanted to do was find out what program you are looking for."

A current admissions employee at South University online, who declined to be identified for fear of retribution, recalled a single mother who was worried about taking out student loans, since she was barely able to pay her utility bills. He figured she wasn't prepared for classes, but his manager told him to turn the situation around on the recruit, asking if she always wanted to be struggling to make ends meet, and implying that a college degree could change things.

A collection of EDMC recruiting documents, obtained by The Huffington Post

All admissions employees interviewed by The Huffington Post described the widely used method of "finding the pain" in prospective students, a tactic employees said was meant to exploit recruits' past failures in careers or education.

A sales call handout obtained by The Huffington Post describes the first three steps when talking to a new sales lead: "1. Build em up! ... 2. Break Em Down! Find the PAIN! ... 3. Build em Up!"

Suzanne Lawrence, who worked in admissions at Argosy University online in 2009 and 2010, remembered recruiting a woman for online classes who had never used the Internet and had no email address. She thought the student wasn't a good match, but she was instead instructed to help the woman set up a Gmail account and get enrolled.

"The scales are so tipped; these people have no way of possibly making a good decision," Lawrence said. "It was like we were used car salesmen. We would basically psychologically manipulate people into doing this. My master's was in clinical psychology, and it was like I was using my powers for evil."

Even recruiters' job titles were intended to be misleading, employees said. An entry-level admissions employee was known as an "assistant director of admissions," a title that lent authority to someone trying to close a sales deal.

"Remember, they don't know you're in a call center," said Klein, the former Argosy admissions adviser. "They think you're at a college, up in an ivory tower, sitting back in a tweed vest with a pipe."

An internal telemarketing script from 2009 obtained by The Huffington Post showed how EDMC recruiters employed dubious corporate titles to persuade students to immediately sign all documents necessary to enroll, not least the financial aid application paperwork.

Recruiters were instructed to create the illusion that they were in a position of power and discretion, telling prospective students they would not receive a "recommendation" if they delayed. In closing calls, the script instructed recruiters to say: "At this point you should understand my role as the Assistant Director of Admissions here at the school" -- a title bestowed on thousands of admissions recruiters. "The school also gives me this position to ensure that you are admissible and to provide a recommendation to complete an application."

Megan Williams, a recruiter at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh online from 2008 until this past summer, recalled the constant drive to enroll students and get financial aid immediately.

"They wanted the app that day," Williams said. "If you're building a relationship with a student, why do I have to close it today? If they want to go to school, they're going to go to school. That was always my outlook. ... That's why I wasn't making the ninety or a hundred thousand that everyone else was making."

A current admissions employee at South University said the drive for numbers has created a recruiting staff that could care less about the well-being or success of the students who are enrolled.

"They're wolves; they're hunters," said the current employee. "They have one objective: They're there to make money and get students."

The changes on the sales side led to major gains for the company. Within three years, EDMC's recruiting force nearly tripled, from about 950 to more than 2,600.

In four years, the number of fully online students increased tenfold, from 4,600 students in 2006 to more than 42,000 students in 2010. Revenues increased from just over $1 billion in 2006 to $2.8 billion by 2011.

THE COSTS OF SUCCESS

But while the infusion of capital from Goldman and know-how from the former Apollo executives has proven beneficial to shareholders, students have fared less profitably: Student loan default rates have grown substantially at several of EDMC's schools.

The most recent student loan default data, released this month, showed that the percentage of students defaulting within two years of leaving at the Art Institute of Pittsburgh nearly doubled, from 7.9 percent in 2008 to 15.4 percent in 2009. South University's default rate increased from 7.9 percent to 13.5 percent between 2008 and 2009.

According to a JP Morgan Chase analyst report in 2010, EDMC's schools have among the highest tuition of publicly traded corporations in higher education. Tuition at EDMC's Art Institutes schools can average about $50,000 for an associate's degree and between $77,000 to nearly $100,000 for a bachelor's degree.

In August, the Justice Department and attorneys general from five states, including Florida, California and Illinois, alleged widespread fraud in EDMC's recruiting model, arguing that admissions employees were compensated entirely based on the number of students enrolled.

EDMC's employee compensation "matrix" did list other "quality factors," such as business ethics, professionalism and job knowledge. But the complaint said that the "so-called 'quality factors' have no real impact on the manner in which EDMC's compensation system is implemented" and amount to "window dressing."

Lawyers for EDMC challenged the notion that the "quality factors" had no bearing on an employee's salary. Bonnie Campbell, a former Iowa attorney general serving as a spokeswoman for EDMC's legal team, pointed out that EDMC had two education law firms independently review the compensation plan to ensure it complied with the "safe harbors" in the law.

"It just cannot be legally said that EDMC relied solely on enrollment numbers, because they didn't," Campbell said. "It wasn't even possible to arrive at an evaluation without a consideration of the quality factors."

An updated copy of the matrix from 2010, which was developed after Nelson arrived and provided to The Huffington Post, shows a chart with the number of students on the left side, and corresponding salary ranges to the right, based on "quality factors" ranging from "unsatisfactory" to "outstanding." The vast majority of the salary increases come from student enrollment numbers.

For example, a recruiter who enrolled a low number of students could only make up to $35,000, even with an "outstanding" quality rating. Yet someone who enrolled the highest range of students but received an "unsatisfactory" quality rating could receive a $73,000 salary; an "outstanding" rating would net the same employee a salary above $114,000.

A copy of EDMC's employee compensation "matrix" from 2010

Current and former employees all said that nothing else mattered aside from the number of students. The quality factors, including "job knowledge," "professionalism" and "problem solving," were merely categories that also were judged based on the number of students enrolled, they said.

"The numbers are honestly what it boils down to," said a current employee at Art Institute of Pittsburgh, who spoke on the condition she not be identified for fear of losing her job. "They do have other components on paper: job knowledge, punctuality, blah blah blah. But those things are never brought up. I've never encountered any type of conversation where I need improvement in any of those other areas."

Campbell said the company has had a "corporate compliance hotline" in place since 2004, where employees could report allegations of any misconduct, including violations of the compensation plan.

"I think it's quite concerning that there are people who now come forward and say that they saw things going on that, by our guidelines, should have been reported at that time," Campbell said.

EDMC responded to the government's allegations in a harshly worded court briefing last week, petitioning for the case to be dismissed. "The government does not and cannot present any facts showing a company-wide sham to defraud the Government," the brief read.

The brief goes on to say that the government was motivated by greed in bringing the case against EDMC -- a company that derives more than 80 percent of its money from the federal government.

"The 'hope of gain,' unsupported by fact or law, does not permit the government to bring a massive, nationwide fraud claim as leverage with which to fill its coffers," the brief read. "The Government should not be allowed to ignore its own law, its own conduct, its own exhibits, and the pleading rules of this Court to make a groundless grab for money to which it is not entitled under any theory."

As federal scrutiny has intensified, EDMC's management has revised many of the sales terms used in training sessions over the past year. For example, the term "pain" was changed to "consequence," according to an internal EDMC document provided to The Huffington Post.

"We will not train or coach our staff to 'dig for the pain' or to manipulate the student's previous misfortune," the document reads. "Instead of dwelling on a past that the student can't change, we train our admissions representatives to facilitate a conversation that considers the Consequence of moving forward without the education."

Instead of "overcoming objections," the new term is "resolving student concerns"; instead of making a "close" on a sales call, a recruiter is now "gaining commitment."

The Justice Department lawsuit could have grave consequences for the future of EDMC. The false claims suit argues that because EDMC violated the recruiter compensation ban, the company unlawfully took funds from the federal government.

False claims suits can technically recover three times the amount of fraudulent claims made to the government. The complaint notes that EDMC has claimed $11 billion in federal money since 2003, meaning that if all $11 billion were found to be fraudulently claimed, the government could recover up to $33 billion, plus additional penalties of up to $11,000 for each government claim, according to the Justice Department.

In the brief filed in August, the Justice Department also called out Nelson specifically, saying he and other former Apollo Group executives should have known that the compensation system violated federal law given the past troubles at University of Phoenix.

"EDMC's senior management knows that the compensation system EDMC implements violates the Incentive Compensation Ban," the brief read. "EDMC knew that its misrepresentations regarding compliance with the Incentive Compensation Ban would result in the payment of federal funds and that a reasonable and foreseeable consequence of such misrepresentations was that such funds would be paid out."

The company pointed out in a statement that the employee compensation practices referenced in the lawsuit were developed before Nelson arrived at the company.

The arm of Goldman Sachs that invested in EDMC is one of the investment bank's private equity funds, meaning there are no requirements for the company to publicly state how much the investment has yielded over time. Goldman's annual filings with the Securities and Exchange Commisison make no mention of EDMC.

Over the past year, Goldman's stake in EDMC has increased from 33 percent to more than 41 percent. Together with Providence Equity Partners, the two firms control 80 percent of the company.

The Justice Department complaint does not specifically name Goldman or Providence as defendants, but their returns could be significantly affected were EDMC compelled to pay penalties and return prior revenues to the government.

But the track record of such false claims suits is spotty. Two former employees at University of Phoenix filed a whistleblower lawsuit against the University of Phoenix in 2003 that involved billions of federal student assistance dollars, but the case was eventually settled with an agreement to pay the federal government $67 million in 2009, which amounts to less than a third of its quarterly income. The Justice Department, however, did not intervene in that false claims case, as it has in the case against EDMC.

"The financial brilliance behind these schools is that unlike the mortgage industry, when this bubble bursts, these loans are guaranteed to these companies," said Lawrence, the former Argosy University recruiter. "They're backed by the government, so it's not them that's going to go under."