Listen to the story in this radio feature from reporter Benjamin Herold:

A stratified system means long odds for students in Philadelphia's neighborhood high schools.

Strolling across Lehigh University's picturesque campus, Jamel Haggins is a striking example of the best that Philadelphia's neighborhood high schools have to offer.

Now a 20-year-old college junior, Haggins is on track to earn his architecture degree next spring. A chiseled 6'3" tall and 255 pounds, he's also an all-conference tight end for Lehigh's football team. Sporting an easy smile and a bright red fraternity sweatshirt -- he's the president of the campus chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi -- the proud North Philly native is a magnet for attention from students and staff alike.

"He's my everything," gushes Haggins' girlfriend, Allison Morrow, the president of Lehigh's Black Student Union.

Haggins was the crown jewel of the class of 2009 at North Philadelphia's Benjamin Franklin High: class valedictorian, a three-time all-Public League football star, and a commanding officer in the school's Navy Junior ROTC.

His former principal calls him "the Michael Jordan of students" — someone to be admired, but clearly in a league of his own.

"He's just different," says principal Christopher Johnson.

Different, most tellingly, because his postsecondary success has not been widely shared by his classmates.

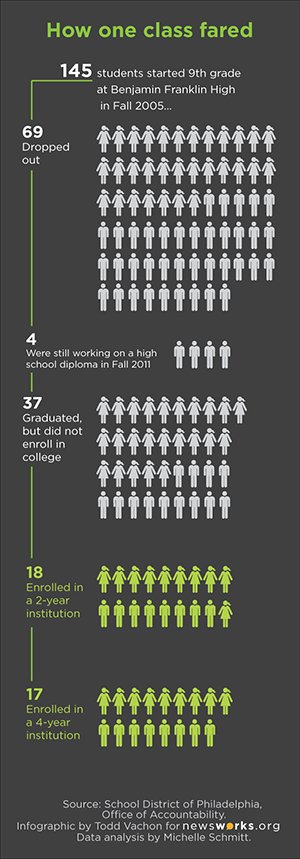

Of the 145 students who started 9th grade at Franklin in fall 2005, only 17 enrolled in a four-year college, according to new National Student Clearinghouse data provided to the Notebook by the School District.

Citywide, only 25 percent of students who started 9th grade in one of Philadelphia's neighborhood high schools that year have enrolled in any postsecondary education, compared to almost 80 percent of students who started at the city's most selective magnet high schools.

"It's unacceptable," said Lori Shorr, the city's chief education officer.

Mired in deep financial crisis, School District officials are trying to expand educational quality by opening up more seats in top-performing schools.

It sounds logical, but Johnson is skeptical.

Even a neighborhood school like Franklin can help the Jamels of the world get to college, says Johnson.

If the city's education leaders really want to fix Philadelphia's broken pipeline to college, it's the kids who can't get into the magnets they should be worrying about.

BELIEVING IN ONESELF

It's Friday evening, and Lydell Boanes is getting high.On music.

"Drumming is like my drug," says a sweat-soaked Boanes, his four-piece quad still strapped to his massive frame after practice with West Philadelphia's Showtime drill team.

"That's what I love to do."

Also a member of Benjamin Franklin High's class of 2009, Boanes, 22, plays and volunteers with Showtime while working part-time as a security guard.

He was hoping to be an electrician by now.

After graduating from high school, Boanes went to Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster. But he was there for only two weeks before learning that his father — absent in his early years, but with whom he built a strong relationship later — was terminally ill. Boanes left school that day.

Later, he enrolled at Thompson Institute, where he earned an electrician's certificate.

But other than $16,000 in student loan debt, says Boanes, he doesn't have much to show for his postsecondary experience.

The credential "carries a lot of weight for me personally," he says. "But I haven't seen any results yet."

Nevertheless, Boanes, who grew up in a violent, desperately poor neighborhood in West Philadelphia nicknamed "The Bottom," counts himself as a success story.

While his father wrestled with addiction, Boanes spent five years in foster care.

In 6th grade, he got caught bringing a gun to Belmont Elementary School.

He started 9th grade at University City High, but was transferred to Franklin after getting into a fight a few weeks into the school year.

Boanes says his biggest problem was that he didn't believe in himself.

"I thought I was, like, a stupid kid," he says. "I couldn't read that good, and everything that I did, I failed."

Once at Franklin, he fell behind in his classes almost immediately, failing both English and math.

But sitting in summer school after 9th grade, something clicked.The staff at Franklin took notice.

Inside the school's Student Success Center, a large basement room filled with computers and couches, Boanes found sympathetic adults eager to help him with everything from math homework to college paperwork.

Inside principal Johnson's office, he found another father figure.

"He always stayed on top of knuckleheads," says Boanes.

"He didn't want nobody to fail."

This piece has been truncated. To read the rest of the story, visit The Notebook.