The time leading up to the 1996 Olympics was the most demanding and stressful of my career. The sport I had loved so much was slowly becoming a nightmare as I trained with Bela and Marta Karolyi the summer before the Olympics. I pushed myself as hard as I could, but I always felt like I couldn’t please them. I kept telling myself that they were just trying to get 100 percent out of me, like any decent coaches, but they were so out of tune with where I was mentally, emotionally, and physically that their tactics were having the opposite effect. I was already fiercely competitive and sharply focused on the goal of Olympic gold.

After years of work and total dedication, it was so close I could taste it. Deep down, I loved gymnastics with all my heart, so I was devastated and confused when I began feeling apprehensive about walking into the gym each morning. Leading up to the most important competition of my career, I felt unprotected and vulnerable in training.

I was so afraid to make mistakes and get reprimanded by my coaches that the joy of the sport started slipping away. Bela would threaten to call (my father) Tata whenever I’d make mistakes. Bela knew he had total control over me, and he used this power to intimidate me, not to motivate or empower me, and I hated that.

Performing my routines -- both compulsory and optionals -- was packed with difficulty, yet executing them was the least of my worries. The real anxiety in the pit of my stomach was fear of Bela and Marta berating me for any error. For most gymnasts, practice is supposed to be the place to get all the mistakes and kinks worked out as the routines are mastered. My routines were nearly perfect already, and we were just putting the final touches on them. I typically did six compulsory beam routines in the morning and six optionals in the afternoon session, and there were weeks when I wouldn’t miss a single routine. I’d challenge myself to see how long I could go without a fall -- on beam, I once went three weeks. I’d go weeks without a fall on my bar routines, but I still felt the pressure every day, every minute, to make zero mistakes because I knew one fall, one slip-up, could set off Bela and Marta and erase all the good I’d done up to that point.

There were times I felt strapped into a straitjacket, trapped living and training at the Karolyi ranch that summer. My every move was monitored by Bela and/or Marta around the clock, 24/7. Spending day in and day out with them, you’d think a personal bond would form, and a certain level of trust would be established, but I could never fully trust either of the Karolyis even though I desperately wanted to. I was terrified of them and found myself counting the days until I could break away. Of course, this meant that I was counting the days until the Olympics were over and done, and that was the most confusing thought of all. I had waited my whole life for this, and now I couldn’t wait to be done with the Olympics, so that I could be done with the Karolyis? This was not at all how I’d envisioned the summer before the biggest competition of my life.

At times, I envied the relationships I saw between other gymnasts with their coaches at competitions. I remembered what it was like to have someone who demanded everything from me but who also believed in me and made me feel good about myself. I wanted that security and support back in my corner. Here I was, heading into the Olympic Games, feeling less confident than ever before with coaches making sure I knew I wasn’t that good.

To make matters worse, I was starting to suffer from chronic sharp leg pains stemming from my right shin. It had been an issue for months and worsened leading up to the US National Championships in Knoxville in June. It was obvious that my leg wasn’t right, and it was affecting my performances, but the Karolyis did not alter my training in response to my injury. I had seen them push other hurt gymnasts. I worked up the nerve to tell Bela and Marta a few separate times that I was really hurting and that I knew something was wrong with my leg. They told me there wasn’t anything “really” wrong with me. By then, my self-esteem had been chipped away significantly, and I actually started thinking that they knew me better than I knew myself, even though, in truth, they barely knew me at all.

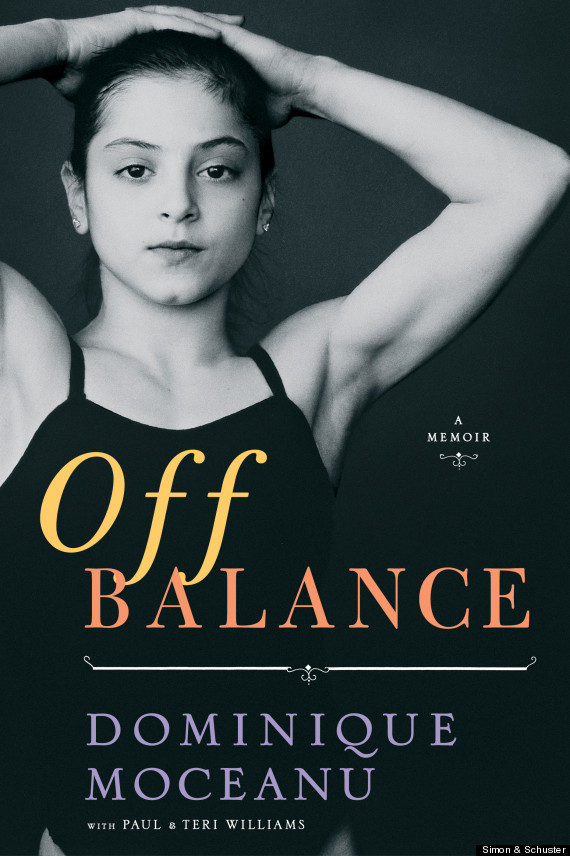

This post is excerpted from "Off Balance: A Memoir" by Dominique Moceanu (Simon & Schuster, 2012).