Last year, 21 freshman members of the House of Representatives made a show of sleeping in their offices. Instead of renting apartments and living among the city's lobbyists, reporters and political hacks, the incoming Republicans wanted to be seen as outsiders, unsullied by the ways of Washington.

"I think it's important that we show we don't live here, we are not creatures of this town," Rep. Joe Walsh (R-Ill.) told CBS News.

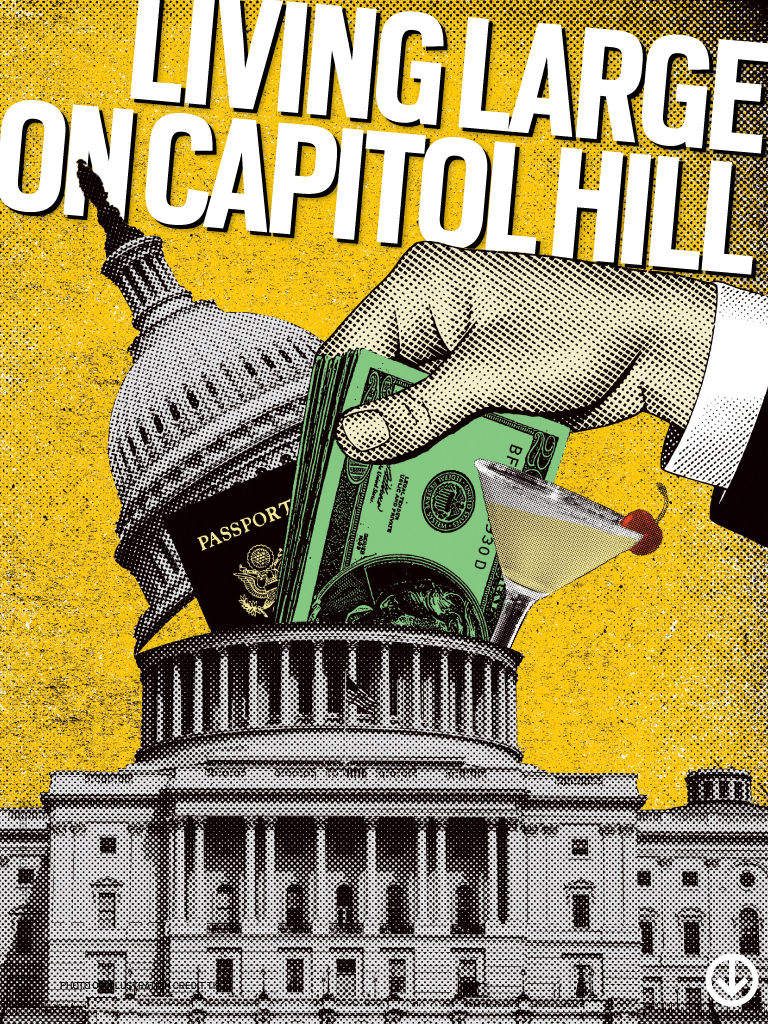

While the ethics reforms of the past two decades have cut down on some of the most egregious displays of excess, Washington can still be very good to the politicians who work here--even Tea Partiers who claim to live like ascetics.

Despite a series of ethics reforms targeting things like outside income and unseemly junkets, members of Congress receive grandiose compensation and live a lifestyle that's too big to fail.

At a town hall meeting in Wisconsin last year, a constituent challenged Rep. Sean Duffy, one of the new Republican couch surfers, about his salary. “I’m just wondering what your wage is and if you guys would be willing to take a cut?” the man asked, according to a video of the event.

The man seemed surprised by Duffy’s answer: Members of Congress make $174,000 a year, the congressman said, after some hemming and hawing.

“That’s three times—that’s three of my family’s—three times what I make,” the constituent stammered. He described himself as a builder who’d been having a hard time finding work since the economy tanked.

Duffy pushed back against the perception that his salary meant he was a member of the nation’s white-collar elite.

“I guarantee that I have more debt than all of you,” Duffy told the town hall attendees. “With six kids, I still pay off my student loans. I still pay my mortgage. I drive a used minivan. If you think I’m living high off the hog, I’ve got one paycheck. So I struggle to meet my bills right now.”

Duffy may have debts, but the reality is that, when compared to the population at large, members of Congress still manage to live on the uppermost portion of the hog. A congressman’s salary is more than three times the median income of American households—currently about $49,445. That paycheck comes fully loaded, with generous health insurance, retirement benefits and other perks that set lawmakers apart from average Americans—and set them up for a lifetime of fortune and comfort.

So, all gestures of austerity aside, the guys and gals on the couches are still doing very, very well, thank you.

PERFECTLY LEGAL

On a recent Thursday morning, Sen. Scott Brown (R-Mass.), another member of the freshman Tea Party class, hosted a breakfast fundraiser at Johnny’s Half Shell, one of Washington’s most popular eateries. Feasts like this are held nearly every day in Washington. Sen. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.), for instance, recently lunched at Art & Soul, the southern restaurant owned by celebrity chef Art Smith.

Lawmakers sometimes complain that they’d rather skip these free meals and do the people’s work, but that the reality of financing a campaign gets in the way. Lobbyists pay thousands of dollars to the politician’s re-election campaign for the privilege of face time with the lawmaker, and doing that over copious amounts of food is part of the drill.

Besides, with the right mix of people, dining for dollars isn’t so bad. “If you’re with people that are kind of fun to hang around with, fundraisers don’t have to be miserable. They can be enjoyable,” said a Republican lobbyist who frequently meals with members but requested anonymity to protect his firm’s business. “A lot of time the guests happen to be a good friend of [the lawmaker’s]. These guys don’t have a lot of spare seconds to relax and have a drink of wine.”

Not to mention they get to eat fancy steaks, free-range chicken and other upscale fare instead of the grub from the Capitol’s cafeterias.

“People rightfully get pissed when they read about the game up here,” the lobbyist said, explaining his reasons for anonymity.

To get some exercise and work off all of that high-end cuisine, current and former members of the House and Senate can make use of two gyms reserved exclusively for them on Capitol Hill. Between them, the gyms offer lawmakers cardio and weight machines, a basketball court, paddle ball court, swimming pool, sauna and steam room. Membership runs $400 a year—a bargain compared to nearby gyms like Results, where annual dues exceed $1,000.

Our lawmakers certainly don’t need to work hard to get to the office or to get around. A private subway system, built in 1909, ferries them the short distance between their offices or committee rooms and the Capitol. When senators approach their members-only elevators, staffers push the buttons and open doors ahead of them so the lawmakers don’t have to wait.

If some Republicans’ offices double as bedrooms, their living room more than makes up for it. On the House side, lawmakers can relax in the Speaker’s Lobby, an opulent, history-soaked lounge with plush chairs and multiple fireplaces just off the House floor. Building staff makes sure the room is stocked with plenty of firewood.

For congressmen, parking in Washington is effectively free. Members on “official duty” are exempt from most local parking laws. And when lawmakers leave Washington and head back to their home districts on Fridays, taxpayers pay the fare. The farther a member’s district is located from Washington, the greater the travel budget to which they are entitled.

Taxpayers also pick up the tab whenever congressional delegations visit foreign countries on diplomatic missions or fact-finding tours—excursions intended to inform lawmakers about international issues and help them do their jobs at home. Still, members of Congress often manage to have some fun while they’re at it.

Lobbyists Heather and Tony Podesta told The Washington Post that they have entertained some 20 members of Congress at their place in Venice over the years.

Rep. Shelley Berkley (D-Nev.) told The Huffington Post in 2010 that she had known the Podestas for 12 years when she met up with them while leading a trans-Atlantic congressional delegation—an official, taxpayer-funded trip—that happened to stop in Venice in May 2008. She did not recall how she and the Podestas arranged their date, but that they ultimately met at a restaurant.

“I didn’t go to cocktails with them, but we had dinner that everybody paid for themselves at a restaurant they recommended,” Berkley said. “But we didn’t talk business at that dinner. That was a strictly Venice dinner.”

(Socializing with lobbyists is legal if lawmakers pay for their own meals and lodging.)

Records provided by Berkley’s office show the trip included 16 other members of Congress at a total cost to taxpayers of $55,000. They spent three days in Slovenia and four in Italy.

Congressional delegations are just one kind of trip. The other experience is often privately-financed. In reaction to the Jack Abramoff scandal, in which the former lobbyist and other K Street denizens won favors by taking lawmakers on outrageous junkets, Congress passed new rules in 2007 restricting what kind of free travel and other giveaways lawmakers could accept from outside groups. The rules also mandated that only nonprofits could sponsor trips.

But Craig Holman, a lobbyist for the watchdog group Public Citizen, says a loophole allows private companies to set up nonprofit fronts to pay for trips, and that privately-funded travel is inching its way back up.

Before the Abramoff scandal, members of the 108th Congress went on more than 9,000 voyages worth $20 million over two years, according to LegiStorm, a nonprofit that tracks congressional disclosure forms.

Members of the current Congress—which still has several months to go—have gone on 2,548 privately-sponsored trips so far, collectively worth more than $8 million, compared with 2,540 trips worth more than $7 million during the 2009-2010 session.

TEA PARTY MOJO

Lavish gatherings of Washington’s power elite were even more frequent in the 1980s—a period The Washington Post’s Sally Quinn recently described as a golden era for dinner parties featuring “a power-filled room of politicians, diplomats, White House officials and well-known journalists.”

Back then, members of Congress made $89,500 a year (the median household income was $24,879 at the time) and supplemented their salaries by moonlighting as speechmakers. The law let members accept $2,000 per speaking engagement, with senators allowed to rake in 40 percent of their salary annually and representatives allowed 30 percent per year.

Common Cause, a watchdog group led by Fred Wertheimer, revealed in 1986 that members had lined their pockets with more than $7 million worth of honoraria in 1985, up from $5.5 million the previous year.

In December 1988, however, Congress prepared to vote themselves a 50 percent pay raise—a proposal that touched off a populist backlash.

“It’s the tea bag revolution .... an updated version of the Boston Tea Party,” Detroit radio announcer Roy Fox told The Washington Post at the time. “The idea came from a listener of mine on Dec. 16, the anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. It was too good to pass up.”

David Keating, then vice president of a conservative group called the National Taxpayer’s Union, which advocates for smaller government and lower taxes, slammed Congress on more than 30 radio shows in fewer than 30 days. He encouraged listeners to send tea bags to Congress with little notes that said “Read my tea bag. No 50% Raise.”

A poll at the time revealed that 82 percent of Americans opposed the pay increase, and members received scores of tea bags through the mail, according to news reports. The teabagging worked: In February 1989, Congress voted down its own raise.

“People are thrilled,” Public Citizen spokesman Bob Dreyfuss told The Post at the time. “It’s almost the only example in recent memory where people actually defeated something by sheer voice of popular opinion.”

Congress won in the end, however. After the outrage faded, lawmakers gave themselves raises a few months later. The deal reined in the honoraria system, restricting gifts and sharply reducing what lawmakers could earn on the side. But it also made annual pay increases automatic from then on, so members could spare themselves the embarrassment of voting to boost their own pay.

Since then, Congress has passed a number of additional ethics reforms, strengthening lobbying disclosure requirements, restricting “soft money” in campaigns and further restricting gifts to members.

Despite these reforms, Congress can still be a ticket to the good life if you play the game right.

THE MILLIONAIRES CLUB

Among the arguments for giving congresspeople relatively generous salaries is that they need the money to maintain residences in Washington and their home districts, without having to rely on integrity-compromising side income.

“That’s good money, but it’s also really expensive on Capitol Hill,” said Brendan Steinhauser, a campaign organizer for FreedomWorks, a Tea Party-oriented group, about congressional salaries.

This rationale is strained, however, by the reality of life on Capitol Hill these days: Congress is rich.

Nearly half of the current crop of federal lawmakers are millionaires, and their median net worth has risen 13 percent since 2008, according to the Center for Responsive Politics’ analysis of financial disclosure forms. Meanwhile, the median net worth of U.S. households fell 35 percent from 2007 to 2010, according to the Census Bureau.

The reason Congress has become stuffed with rich folks, analysts say, is that the cost of political campaigning has soared.

“It’s very simple,” says Jim Manley, who worked as a Democratic congressional staffer for 21 years before joining a public relations firm last year. “If you are going to slash members’ pay you are soon only going to see the very wealthy or the incompetent run—and we already have enough of both right now in Congress.”

Others agree that the cost of campaigns is larding Congress with millionaires, but not necessarily that the barriers to entry justify the compensation.

“Campaigns have become so taxing we elect millionaires,” says Public Citizen’s Craig Holman. “That’s where the rationale [for the current compensation scheme] falls apart.”

Another argument for paying lawmakers well is that they shoulder a considerable amount of responsibility. “It’s not the job of the average person in America to be an elected representative, to make national decisions about how we raise and spend our money, whether we go to war,” says Fred Wertheimer.

Wertheimer, who helped lead the charge against the corrupt honoraria system in the late 1980s, says he considers $174,000 a reasonable salary given the work that lawmakers are required to perform.

But how hard are they working?

A recent CNN analysis showed that the current Congress has passed just 132 bills. The previous Congress passed 383. Divided government isn’t the only explanation: The 107th Congress of 2001-2002 passed 377 laws despite the fact that one party didn’t control both chambers.

The Chicago Tribune, measuring votes taken, bills made into laws and nominees approved, reported last year that the current Congress is even underperforming the “do-nothing Congress” of 1948.

On the other hand, to some people—especially conservatives —fewer new laws might be a good thing. And an unproductive Congress could just be a democratic reflection of a divided electorate. But if people are happy with what Congress is doing, it doesn’t show. In February, Congress achieved its lowest approval rating in the history of the Gallup poll.

Even Wertheimer said people might start to wonder why politicians are paid so highly if they aren’t doing their jobs well. Members “are raising questions for themselves because of the extraordinary gridlock in Washington,” he says.

Calls have arisen again within Congress for paycuts. Eight bills in the current Congress would repeal the annual automatic pay adjustments (members have voted not to accept increases for the past three years); nine bills would connect congressional pay to outside economic indicators; and four bills would just cut the pay.

“The last time Members of Congress took a pay cut was on April 1, 1933—in the midst of the Great Depression,” wrote a group of lawmakers last fall to the co-chairs of the so-called “super committee,” who were seeking a grand bargain on deficit reduction. “At a time of similar economic turmoil and record deficits, Congress should not require sacrifices of others without tightening its own belt.”

The same group of lawmakers noted that legislators in other developed nations are paid 2.3 times more than their constituents, while American legislators earn 3.4 times more. (Only Japanese lawmakers are paid better relative to the people they represent than American lawmakers.) A 10 percent pay cut would deliver $100 million worth of savings over 10 years, the American lawmakers noted in their letter to the super committee.

Still, some lawmakers cry poverty. Freshman Republican Rep. Scott Rigell (Va.) said he doesn’t support slashing salaries because some members really need the money (though he told the Huffington Post that he himself hands back 15 percent of his salary to the government as a matter of principle).

“I know after votes are finished, when I’m walking back to a place, going back to a regular bed, many of my colleagues are not going to an apartment,” says Rigell. “They’re going to their offices because that truly is all they can afford.”

After more than a year since their arrival in Washington, 12 out of the 21 congressmen who vowed to live in their offices say they’re still committed to couch surfing, according to their spokespeople. One, Rep. Richard Hanna (R-N.Y.), admitted to giving up, though his office declined to say why. The rest did not respond to multiple requests for information.

Duffy, who is among the committed couch surfers, told his constituents at the town hall last year that he’d support a salary reduction. “Let’s go across the board and all join hands together,” he said. “Let’s all take a pay decrease, and I’ll join with you. Absolutely.”

None of the current paycut proposals are expected to go anywhere, however. After all, a member of Congress offering to cut his own pay is like the guy who makes a big show of reaching for his wallet when someone else has already offered to pay for dinner.

“Those bills are just politicking,” Holman says.

Exactly, say others.

“There is a reason why it’s usually the freshman members who introduce bills calling for a reduction in members’ pay,” Manley notes. “That’s because it is nothing more than a cheap political stunt guaranteed to get favorable press coverage or kudos’ from so-called pro-taxpayer groups.”

An action lawmakers did approve last year was a 5 percent cut to budgets for their own offices. While the vote didn’t affect congressional compensation, it did prevent raises for many lesser-paid staffers. Lawmakers nevertheless thumped their chests about how they were tightening their belts just like regular Americans.

“Everybody knows that across this country families and small businesses have cut their spending, are paying off their debt, and are striving to live within their means,” Rep. Dan Lungren (R-Calif.) said on the House floor before the budget-cutting vote. “We should do the same.”

Some staffers aren’t impressed.

“I’m not mad because we didn’t get raises. I’m mad because they used this as a political issue,” says one Republican House staffer, who after 16 years of service earns less than $60,000, and requested anonymity to protect her job. “In their office budget, they still have plenty of money to get all new BlackBerrys, new computers, flat screen TVs, iPads—every little thing. They don’t cut back on travel expenses, but yet they make it look like they’re sacrificing.”

Holman said he’d be open to a means-testing setup that pays lawmakers less if they’re really rich—something similar to what many lawmakers embrace for safety net programs like Social Security and Medicare.

Pete Sepp, a spokesman for the National Taxpayers Union, said many of his group’s members also favor reforming another lush congressional benefit: pensions.

While employees around the country are watching their retirement benefits vanish, congressional pensions remain generous—two to three times more than what similarly-salaried private-sector workers typically get, according to Sepp. After five years of service, lawmakers who are 62 or older can draw lifetime income. The longer they serve, the greater the proportion of their salary they receive, up to 80 percent if a member has put in 32 years or more.

“It is therefore no wonder that taxpayers, who often struggle to provide the most meager of retirement benefits for themselves, find Congress’s package so offensive,” Sepp wrote in an open letter to Sen. Mark Kirk (R-Ill.) in 2011. “This is especially true since the contributions lawmakers provide to the system cover only a fraction of their typical lifetime payouts.”

Where does the rest of the money come from to fund lawmakers’ pensions? Taxpayers.

Great health insurance has long been another perk of a job in Congress (although the health care reform law will force lawmakers to participate in health insurance “exchanges” like the rest of us in 2014). Until then, members can choose from a variety of plans available to federal employees. They can’t be excluded because of pre-existing conditions, and enrollment doesn’t require a waiting period. By contrast, 74 percent of workers with employer-sponsored health care face waiting periods averaging 2.2 months, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

After leaving Congress, lawmakers eligible for pensions have been allowed to keep their health insurance, too (another perk that will evaporate in 2014).

When all is said and done, the biggest perk a legislator corrals is when he or she finally calls it quits and wanders over to K Street. An influential former senator or chairman of an important committee, for example, can fetch a seven-figure salary as a lobbyist or “adviser.”

No fewer than 160 former members of Congress are registered as lobbyists today, according to First Street, a lobbying analytics company. And that total excludes the many former lawmakers, like Tom Daschle and Chris Dodd, who are top advisers to K Street firms but haven’t officially registered as lobbyists, which is easy to avoid thanks to the law’s narrow definition of lobbying. Daschle, for instance, can wield all the influence he wants so long as he doesn’t personally make more than one phone call in an effort to influence legislation. If an underling does it for him, though, that’s fine. (Dodd and Daschle did not respond to requests for comment.)

Among the non-lobbyists are former Sens. Robert Bennett (R-Utah) and Byron Dorgan (D-N.D.), who took jobs last year with D.C. law and lobbying firm Arent Fox. Arent Fox’s chairman said in a statement announcing the hires that Bennett and Dorgan “will add a tremendous amount of proven strategic, policy and business expertise that is important to our clients and our law firm.”

The Huffington Post asked the senators if they were concerned critics might accuse them of cashing out. Dorgan didn’t respond but Bennett was game.

“Is there anything in the Constitution that forbids me from earning a living?” he said. “I have skills, people want to pay me for my skills, I want to earn a living, and this is the way I do it.”

When asked how much money he would be making, Bennett paused.

“Enough,” he said.

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store