When Kathryn Treadway pulled into the driveway in a tree-filled subdivision in Kinston, N.C., at 9 a.m. on a Friday in May, 2011, she didn't know whether the man who lived on the three-and-a-half acre property would welcome her or call the police.

They had never met in person, but the previous evening they had sparred over email.

The owner of the house, Stephen LaRoque, was a senior Republican in the North Carolina House of Representatives. He had helped his party stall a measure to maintain the state's eligibility for long-term federal unemployment insurance.

North Carolina's unemployment rate was 10.5 percent at the time, and the standoff in the statehouse had stopped checks for 47,000 long-term unemployed North Carolinians-- many of whom had already depleted their savings trying to keep their lights on and their children warm with a fraction of their former income.

Treadway, then 35, was one of them. She'd lost her job doing medical transcription work early in 2010, and she and her husband had two young kids to feed. She wrote LaRoque and other top Republicans explaining her troubles.

"I am begging you on behalf of our family, before we lose absolutely everything, to please work out a compromise and pass the extension of these benefits to give us more time to try to help ourselves," she said in her email.

Most politicians might have responded to such a plea with a boilerplate letter thanking Treadway for her views on the matter -- if they bothered to respond at all. But LaRoque, then 47, wanted to help. He suggested that Treadway apply for work at a nearby chicken processing plant. Having already applied there and been told no jobs were available, Treadway called LaRoque dishonest. He quit being nice.

“Most anyone can find a job if they can pass a drug test and are physically able to work,” he replied. “I have tried to find people to do yard work but it seems most are too good for manual labor. Based on the tone of your email it is not difficult to see why you can’t find a job.”

LaRoque told Treadway that if she was really willing to work, he’d pay her $8 an hour to clean his yard. She drove from her home in Goldsboro, 26 miles away, the next morning, ready to get dirty, she told The Huffington Post at the time. (Though both Treadway and LaRoque spoke with HuffPost in the past, neither agreed to be interviewed for this article.)

The incident between Treadway and LaRoque is more than just a local squabble. Republicans at the state and federal levels broadly share his view on the plight of the unemployed, a view that often comes down to a simple, and simplistic, distillation: Able-bodied people who don’t work are just lazy, and it shouldn’t be the government’s job to help them.

GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney espoused the view earlier this year, when he told donors at a private campaign fundraiser that he believed that half the country is dependent on government.

“I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives,” Romney said.

Just as Romney’s tough talk about personal responsibility seems out of sync with his own privileged background, LaRoque, too, has seemingly played by a different set of rules. His job offer to Treadway may have triggered a sequence of events that shredded his own tale of personal success achieved solely through bootstrap entrepreneurship and ultimately led to a grand jury indictment — leaving him on the verge of possibly losing everything he has.

A MAN WITH IDEAS

LaRoque hadn’t always taken such a hard line on workers. After earning an MBA from East Carolina University in 1993, he founded two nonprofits, the East Carolina Development Company in 1997 and the Piedmont Development Company in 2004.

The nonprofits acted as a transit point for loans from a U.S. Department of Agriculture lending program aimed at alleviating poverty and spurring economic growth in low-income, rural areas nationwide. Known as the Intermediary Relending Program, it allowed groups like LaRoque’s to borrow the money at a one-percent interest rate and then relend it at a higher rate to struggling rural businesses, with the idea that the groups would use the profits to pay operational costs and relend principal that borrowers had paid back.

When LaRoque won his seat in the General Assembly in 2002, representing North Carolina’s 10th District, a local reporter with the Morning Star of Wilmington, N.C. accompanied him on a drive to see some of the homes that had gone up thanks to ECDC loans to a local developer. Hurricanes had recently caused flooding in the area, and 13 displaced families had taken up residence inside the brick-and-vinyl homes.

“A flooded-out family moved into that one,” LaRoque said, slowly driving by the buildings, “and a group of about six older people on Social Security who were flooded by [Hurricane] Floyd live in that one.”

LaRoque told the reporter that he planned not only to bring fiscal discipline to the statehouse, but also to make sure the state actively promoted economic development in his district, which had lost six percent of its residents during the 1990s due to flooding and a lack of jobs — even as the state saw 21 percent population growth during that period. LaRoque’s relative open-mindedness had even earned him the support of some local Democrats.

“Let me put it this way: This state, county and nation are in a crisis situation, economically,” Lenoir County Commissioner Oscar Herring, a Democrat, told the reporter in 2002. “We’ve got to do something about it, and Stephen was a man with ideas. He impressed me.”

In January 2003, disaster struck LaRoque’s district again when an explosion destroyed a pharmaceutical plant, killing six people and injuring 36 in the town of Kinston. That February, LaRoque championed a bill to make sure surviving workers would receive unemployment compensation because their jobs had been lost.

“The folks in Kinston really need this,” LaRoque told reporters, according to the Associated Press. “They’ve got rent to pay the 1st of March and they’ve got grocery bills.”

By 2011, however, well into the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression, many Republicans at the state and federal levels had grown tired of treating unemployment as a disaster. In North Carolina, when it came time to pass a law so the state’s long-term jobless could continue receiving federal unemployment insurance, Republicans there saw an opportunity.

They tried to use the benefits as leverage to extract major budget cuts from Democratic Gov. Bev Perdue. But Perdue didn’t give in, and tens of thousands of jobless workers became collateral damage as Republicans held up their benefits in a legislative standoff that dragged on for weeks. Treadway claimed in her email to LaRoque that her family had lost its home to foreclosure during the impasse.

Perdue eventually defied Republicans with an executive order that unilaterally reinstated the benefits. She cited unnecessary eviction notices in her order. “The people I hear from say they can’t keep the lights on,” Perdue said. “Banks are ready to foreclose.”

For Republicans like LaRoque, the issue was a philosophical one. Unemployment was at least partly a failure of personal responsibility, rather than solely an economic problem beyond the control of individual workers.

But for North Carolina’s long-term unemployed, the battle over jobless benefits was personal.

“You and your party promised to represent us when we needed you and you have failed miserably,” Treadway said to LaRoque in their email exchange. “I sincerely hope karma comes around to bite you in the butt when election time comes.”

A FIGHTIN’ MAN

However collaborative and appealing to Democrats LaRoque had been when he first ran for office, by 2010 a more combative side started to show. He had been voted out of office in 2006, but by 2010 wanted his seat back from Democrat Van Braxton.

Braxton played hardball, distributing campaign flyers that alleged LaRoque, through his rural lending operation, screwed the proprietor of a barbecue restaurant through irresponsible lending that ended in foreclosure.

“LaRoque stole my business,” Bruce Patterson, the business owner, said in the flyer. “He stole my home.”

Patterson had borrowed $379,900 from the East Carolina Development Company in the late ‘90s, but fell behind on payments in 2006, leading ECDC to foreclose on both the restaurant and Patterson’s home upstairs. Patterson claimed LaRoque pushed the financing on him, then wouldn’t negotiate a modification when times got tough.

LaRoque insisted he hadn’t done anything improper, and then sued Braxton for defamation, continuing the case even after he’d won back his state seat. Braxton’s legal team began requesting documentation from LaRoque. The lawyers had uncovered an audit by the USDA’s Office of the Inspector General questioning LaRoque’s business practices and suggesting, as Braxton’s attorney put it to the Kinston Free Press, “that LaRoque may owe $4.5 million back to the government for making loans in violation of the program under which he was operating.”

LaRoque stonewalled, refusing to cough up documents and finding himself in contempt of court — all for an election he’d already won. It wasn’t the only unnecessary fight he picked.

In May of 2011, two weeks before he met Kathryn Treadway, LaRoque took offense to a press release from the local NAACP that said Republican obstruction of unemployment insurance would harm the state’s African-American population. LaRoque called the NAACP “racist.” He told local TV station WRAL, “I’m sick of getting these race-baiting, racist-type action alerts, e-mails, whatever you want to call them.”

In the midst of all of this, Treadway pulled into LaRoque’s driveway last year, ready to take on the job he’d offered. LaRoque greeted her politely, according to both of their accounts at the time, and began fulfilling his promise to give her work. He got her started pulling dead tomato and bell pepper plants out of pots, then pouring the soil into a big container so he and his wife, Susan, could reuse it later. After that, he asked her to clear some fallen tree limbs from the yard.

Treadway quit after one hour.

“It was just too much. I’m not used to doing manual labor, and the crap he wanted me to do was something two men would do,” she told The Huffington Post at the time, adding that she thought LaRoque deliberately tried to humiliate her. “I’m used to making $22 an hour. I’m not gonna sit there for $8 an hour and come home having a stroke.”

LaRoque paid her $8 in cash, and she drove home.

“If people need a job, they need to go looking for a job, and they need to take what they can get until they can find something better,” LaRoque told HuffPost after the incident, vindicated in his view of joblessness. “I still think that a lot of those people are not actively looking for work.”

The online community reacted strongly to a Huffington Post story in May 2011 about Treadway’s fight with LaRoque. Online commenters criticized LaRoque and posted his email address and phone number at the North Carolina General Assembly.

LaRoque jumped into the article’s comment thread to defend himself, leaving more than 100 spirited comments over two days. Most of them calmly answered other commenters’ questions, but in a few he let his exasperation show.

“Sir you just called my deceased mother a Bitch,” LaRoque wrote in one comment. “I dare say you wouldn’t do that to my face...You are a real ASS!”

“So you want to get rid of the state legislature?” he said in another. “That’s a real bright idea...Did you come up with that one on your own?”

In response to claims that he’d been a cheap boss, LaRoque contended that he himself made very little money from his part-time job as a state legislator. His annual statehouse salary of $13,950, divided by the number of hours he worked, he said, amounted to an hourly wage of $6.71.

“If I were to make $8 an hour that would be a 19% increase and I don’t think the taxpayers of North Carolina would appreciate the legislature giving itself a 19% wage increase,” he wrote. “My net pay each month is $44 and change. That equals about $1.50 a day or about 19 cents an hour.”

But being a state rep wasn’t, of course, LaRoque’s only gig. His online antagonists quickly started seeking more information. Several readers looked up the East Carolina Development Company’s tax forms online and discovered that LaRoque earned a low six-figure salary from that organization alone. They emailed the documents to journalists, including Sarah Ovaska, a reporter who had been covering the unemployment standoff at the statehouse for N.C. Policy Watch, a local, left-leaning think tank.

After receiving the tip, Ovaska began digging deeper. Over the course of a two-month investigation, she discovered that LaRoque had paid himself hefty salaries for a decade, mainly from ECDC, and that he loaned federal money to friends and political allies. He put his wife and brother on his two nonprofit companies’ boards of directors, and kept other board members uninformed about his pay. (Having family members on a board isn’t illegal, but it’s frowned upon by the IRS for conflict-of-interest reasons.)

Ovaska also found the same USDA audit criticizing LaRoque’s use of the Intermediary Relending Program that Braxton’s lawyers had used in their court battle. LaRoque, Ovaska noted in her story, had a record of “questionable management and financial dealings.”

Shortly after Ovaska’s story came out in August 2011, LaRoque called a press conference to denounce her findings. He called N.C. Policy Watch a “liberal propaganda tabloid” and claimed that his compensation at the non-profits was commensurate with the assets he managed.

LaRoque also said his salary at the non-profits came from interest on loans that borrowers paid back, not from taxpayer dollars. Moreover, he noted, Ovaska’s article had been an act of retaliation — the head of the NAACP’s North Carolina chapter sat on the board of a group affiliated with N.C. Policy Watch, which published Ovaska’s article, and Laroque pointed out that he had once criticized the chapter head as a racist.

LaRoque’s press conference failed to clear his name.

A DIFFERENT PERSON

In September 2011, shortly after the N.C. Policy Watch story came out, state and federal authorities subpoenaed LaRoque as part of a joint investigation into ECDC’s activities as a non-profit.

In July of this year, the investigation — which included the Internal Revenue Service, the USDA, the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation — produced a 72-page grand jury indictment charging LaRoque with four counts of theft and four counts of fraud. If found guilty on all counts, LaRoque faces 80 years in prison.

The timing of the subpoenas led most local reporters to conclude that Ovaska’s journalism had sparked the investigation, but it’s possible authorities had already been looking into LaRoque because of the defamation case. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of North Carolina, which announced the indictment, declined to comment on the investigation.

John Archie, Van Braxton’s lawyer, said he figured authorities would jump on LaRoque based on what he’d uncovered in the discovery process for the defamation suit. “We got to the point where everybody was fairly comfortable that something was going to happen with the feds so we settled the lawsuit.”

LaRoque dropped the defamation case last November — after he’d been subpoenaed in the federal investigation — and paid $17,250 in contempt fines.

Whether it was his foray into an Internet comment section or his lawsuit against an already-defeated opponent that led to LaRoque’s downfall, there’s no question that his willingness to jump into battle also played a role.

“He’s just a different person,” said Braxton, when asked why LaRoque is so combative in court and online. Braxton said he grew up in Kinston but only knew LaRoque from the campaign. “I think he’s got strong convictions and he’s willing to go out of the norm and defend his positions and himself. It’s probably an attribute most politicians and elected officials would not do.”

It turned out the defamation case and Ovaska’s investigation uncovered only part of the story. For a decade, the indictment alleges, LaRoque overpaid himself from his non-profits and stole federal loan money to, essentially, go shopping.

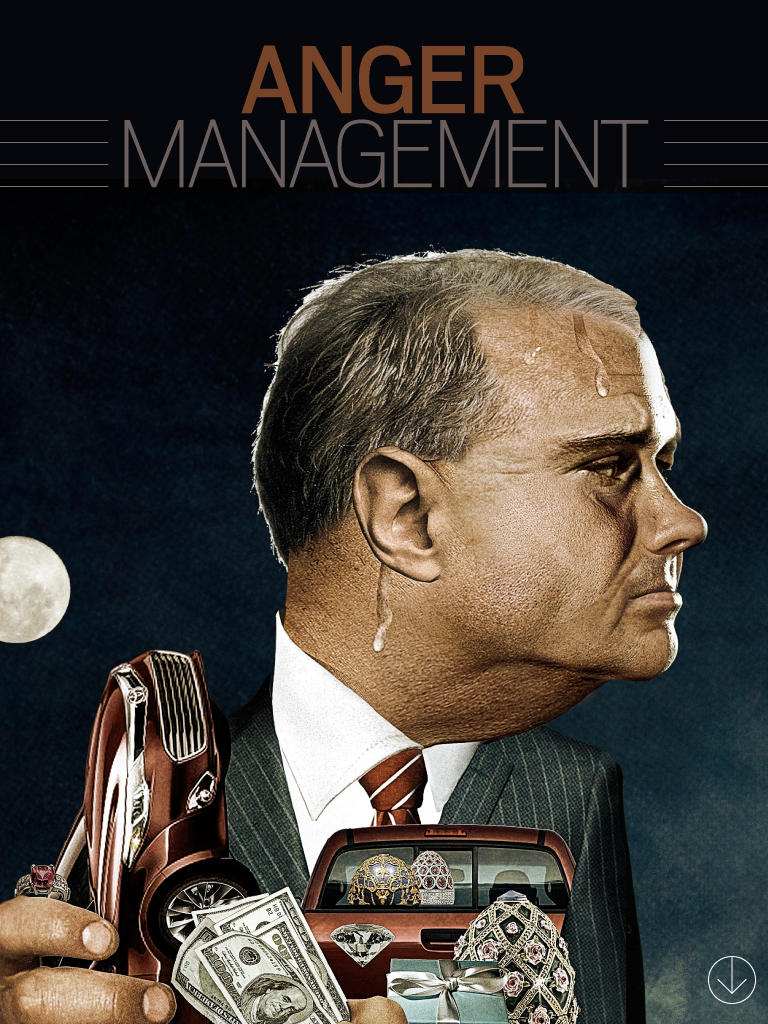

According to the indictment, in 2005, LaRoque used taxpayer dollars to buy himself a new Toyota Avalon for $37,729. In 2007, he did it again to buy a slightly used Toyota Tacoma for $21,958. A week before his wife’s birthday in February 2008, he spent nearly $10,000 on jewelry, including two Faberge-style eggs. In December 2008, LaRoque allegedly used company money to buy more than $15,000 worth of Faberge-like eggs and Faberge egg-themed jewelry, including a necklace and earrings.

The jewelry was allegedly for LaRoque’s wife, Susan, whom the indictment suggests LaRoque met through his business. In 2001, the ECDC lent $150,000 to a company called Susan’s Carpet and Interiors, which Susan Eatman owned, at a lower interest rate than other ECDC borrowers received. Later that year, Susan’s Carpet installed carpet in LaRoque’s home, which LaRoque again paid for with ECDC funds. Shortly thereafter, Eatman (described in the indictment either as “Susan’s Carpet Owner” or “LaRoque’s Wife”) joined the ECDC board. LaRoque married her in 2007.

In January 2009, Susan LaRoque sold her carpet business in hopes of buying an ice skating rink in Greenville, N.C., according to the indictment. Later that year, with yet more funds from ECDC, she bought Bladez on Ice for a few hundred thousand dollars. ECDC money also was used to buy a new zamboni. In 2010, the indictment alleges, LaRoque and his wife also illegally used taxpayer dollars to buy a house for her daughter to rent.

LaRoque’s lawyer told the North Carolina News & Observer that LaRoque will be vindicated in court. His Republican colleagues in North Carolina’s General Assembly seem less supportive. After the grand jury indicted LaRoque in July, State House Speaker

Thom Tillis asked LaRoque to resign.

LaRoque obliged.

“I do not want my continued presence in the General Assembly to be politicized or to distract from the important work that still needs to be done there,” he wrote in a letter to Tillis. The trial will start early next year.

LaRoque’s days as a lawmaker might have been numbered anyway. He lost a close primary contest in May. Ahead of the election, he explained to a local reporter how he evaluated himself as a lawmaker.

“I tell folks my greatest accomplishment’s when I can help a constituent, and my worst failure’s when I can’t,” he said.

This story originally appeared in Huffington, in the iTunes App store.