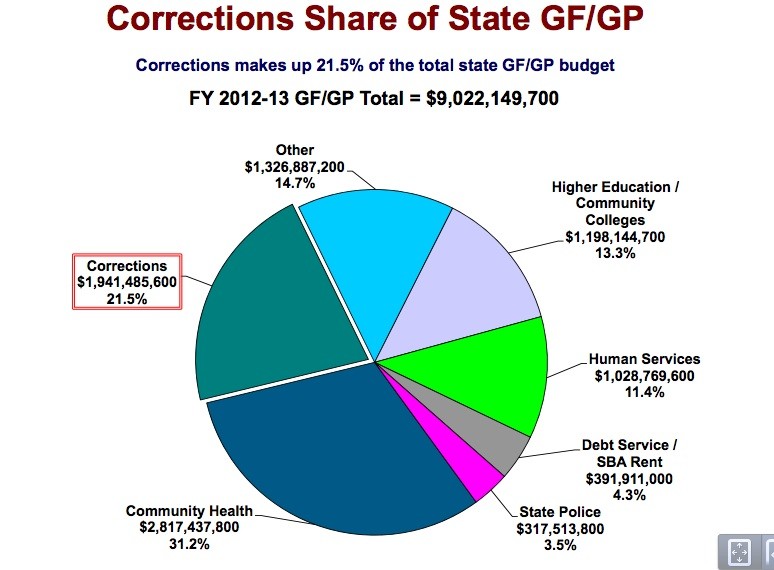

Looking to cut a corrections budget that accounts for nearly a quarter of the state's general fund each year, Michigan lawmakers have reopened the door to privatizing state prisons.

Prison systems constitute a major slice of state budgets across the country, prompting legislators to explore savings measures. Under legislation signed into law by Gov. Rick Snyder (R) this week, Michigan could send inmates to a troubled private prison or privatize other prisons as part of an effort to trim costs in the state's $1.9 billion corrections system.

The legislation is a potential boon for the GEO Group, the nation's second-largest for-profit prison operator, which owns a now-vacant youth prison in rural Baldwin, Mich. Ever since the state canceled its contract with GEO in 2005, company executives have unsuccessfully tried to find inmates to fill the 1,725 empty prison beds. The company boosted its spending on political lobbying in Michigan more than fivefold last year.

But the Baldwin prison has a checkered past. The state closed the facility, its only private prison, in 2005, following a series of audits and investigations that found high levels of assault, frequent staff vacancies and operating costs that exceeded those in comparable state prisons.

Civil rights and criminal justice policy groups argue Michigan cannot ignore its troubled history with privatization. "There's absolutely no reason to think that conditions will necessarily be better, or that problems like staff turnover will have been solved," said Barbara Levine, executive director of the Citizens Alliance on Prisons and Public Spending, a Michigan group that advocates for sentencing reform and reducing prison populations. "There are a lot of lessons to be learned."

Michigan's experience with privatization offers a case study of the challenges many states have faced in outsourcing public safety to for-profit corporations: Cost savings often don't materialize, and lower wages lead to high rates of turnover, which critics say compromises safety.

Private prison corporations such as the Florida-based GEO Group grew in the 1980s and '90s as state prison populations soared, and in more recent years as the federal government detained record numbers of undocumented immigrants. The companies have angled for growing shares of state and federal inmates, promising cost savings for governments struggling to balance budgets.

But those savings have often proven illusory, according to a series of reports by federal and state auditors. State reports in Arizona, where nearly a quarter of the prison system is privatized, have found that medium-security private prisons cost more than state prisons when factoring in medical care and other costs. Studies on Florida's private prisons have also shown minimal cost savings, despite state requirements that private facilities must produce savings of more than 7 percent.

Michigan state Sen. John Proos (R), who introduced the prisons bill last year, said the legislation is part of a broader effort to determine whether private contracting can bring down costs across the corrections system -- for food services, transportation and healthcare, in addition to outright management. Any contractor would be required to demonstrate a 10 percent cost savings.

"This is a colossal industry in the state of Michigan that requires constant and diligent management," Proos said. "The only way I could get my arms around the budget question of whether or not we are adequately using taxpayer dollars to provide those services was to ask the private sector to bid for those services."

Graphic courtesy of Michigan House Fiscal Agency

Proos said the new law does not mandate that any prison be privatized, but he expects the state to begin asking private companies to submit proposals. A spokesman for the Michigan Department of Corrections did not respond to requests seeking comment.

Earlier versions of the prison privatization bill focused specifically on authorizing the state to contract again with the GEO Group facility in Baldwin. The current legislation addresses prison privatization more broadly, and it contains language that allows the GEO facility to house Michigan adult prisoners.

A GEO Group spokesman, Pablo Paez, wrote in an email that the company has a policy of not commenting on legislative matters or competitive bids.

The Baldwin prison dates back to the late 1990s, when the state was looking for a private contractor to run a new prison for young males who were convicted of serious adult crimes. GEO, which was then called Wackenhut Corrections Corporation, opened the North Lake Correctional Facility in 1999, and problems started to emerge soon after.

A local newspaper, The Grand Rapids Press, published an investigative series in 2000 that found high rates of serious incidents, such as assaults and attempted suicides, at the youth prison. Such incidents were occurring at three times the rate of the state's maximum-security prisons, according to the findings.

A state audit in 2005 concluded that a high rate of staff turnover at the private facility was another serious problem, one that could "negatively impact the safety and security" of the prison, according to the audit.

The audit also found that the prison wasn't saving the state any money, and that inmates could be transferred to existing state facilities at lower costs.

Paez, the GEO spokesman, did not respond directly to questions about the operational issues at the Baldwin prison, saying only that the company is "proud of its long-standing partnerships," including with government officials in Michigan. He wrote in an email that the prison is a "state-of-the-art facility" that abided by the state's contractual requirements and "adhered to the highest national standards."

In 2005, then-Gov. Jennifer Granholm (D) vetoed additional funding for the youth facility, over protests of Republicans in the legislature, a decision that saved the state $18 million. GEO Group and local governments near the prison sued, claiming a breach of contract, but the courts sided with the state.

After Michigan canceled the contract in 2005, GEO Group continued to try to fill the prison and recoup costs. Beginning in 2008, the company embarked on a $60 million plan to expand the prison from 500 beds to more than 1,700 -- even though there were no prisoners.

The speculative prison expansion was needed to attract new government customers and achieve the proper "economies of scale for our prospective clients," GEO chief executive George Zoley said in a 2008 investor conference call. The company tried marketing to the federal Bureau of Prisons to house criminal undocumented immigrants, but cost cutting at the bureau halted any new contracts.

In 2010, California signed a deal with GEO to send more than 2,500 prisoners to the Michigan facility. But less than a year later, the state reversed course and asked for its inmates back -- part of a California prison realignment plan that brought out-of-state inmates home.

Beginning in late 2011, legislators in Michigan started introducing bills that would allow the GEO Group to house state prisoners again. According to state lobbying records, the GEO Group spent nearly $30,000 lobbying during the first half of last year, a more than tenfold increase from the same time period a year before. One of the company's lobbyists is Rick Johnson, a former speaker of the Michigan House.

Proos, the senator who sponsored the prison bill, said any past problems with the GEO Group in Michigan or other states should be taken into account when state officials evaluate any contract proposals.

"You want to make sure that you're spending these tax dollars wisely, and for good benefit," he said. "What we can't do is sit by and allow the costs to continue to skyrocket."

Staffing is the most expensive cost in any prison system, and wages tend to be lower at private prisons, where correctional officers are generally not unionized. Michigan lawmakers passed the prison privatization bill during a lame-duck legislative session last month, alongside right-to-work legislation that is expected to dampen the power of unions in the state.

Critics of privatization argue the most substantial cost savings would come from broader reforms in sentencing and parole laws, not through lower-paid staff at a private facility. A report released by the Pew Center on the States last summer found that Michigan had the longest average length of stay for prisoners out of 34 states analyzed.

The study found that significant numbers of non-violent offenders were being released after long sentences, and that Michigan could reduce its average daily prison population by 3,300 without any impact on public safety -- for an estimated savings of $92 million a year.

Discussion around reopening the Baldwin prison also comes despite a decline in Michigan's prison population in recent years. Several state-owned prisons are also empty, prompting questions about why Michigan would need to reopen a private prison and force a major realignment of the system.

Natalie Holbrook, a co-director of the Michigan criminal justice program at the American Friends Service Committee, a justice reform group, said the state should be thinking about long-term impacts when considering ways to trim costs.

"You save money if you close down a prison, not open a new one," she said.