Every job candidate lives in fear that a Google search could reveal incriminating indiscretions from a distant past. But a new study examining racial bias in the wording of online ads suggests that Google's advertising algorithms may be unfairly associating some individuals with wrongdoing they didn’t commit.

After learning that a Google search for her own name surfaced an ad for a background check service hinting that she’d been arrested, Harvard University professor Latanya Sweeney set out to investigate whether race shaped online ad results. She searched over 2,000 “racially associated names” to determine if names "previously identified by others as being assigned at birth to more black or white babies" turned up ad results that indicated a criminal record. Specifically, she focused on ads purchased by companies that provide background checks used by employers.

Sweeney concluded that so-called black-identifying names were significantly more likely to be accompanied by text suggesting that person had an arrest record, regardless of whether a criminal record existed or not.

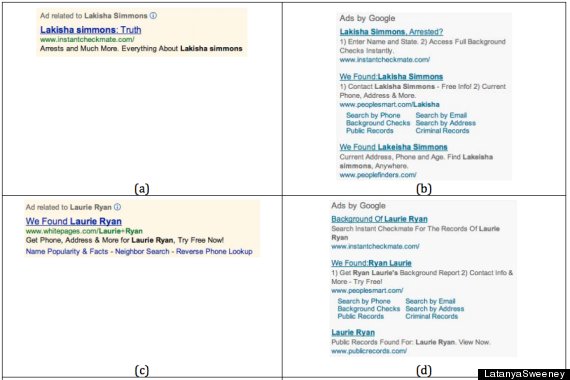

On the left, ads delivered for full name searches on Google.com, according to Sweeney's study. On the right, ads delivered for full name searches done via Reuters.com, which offers Google results. Via Latanya Sweeney.

On the left, ads delivered for full name searches on Google.com, according to Sweeney's study. On the right, ads delivered for full name searches done via Reuters.com, which offers Google results. Via Latanya Sweeney.

“There is discrimination in delivery of these ads,” Sweeney writes in her report. “Notice that racism can result, even if not intentional, and that online activity may be so ubiquitous and intimately entwined with technology design that technologists may now have to think about societal consequences like structural racism in the technology they design.”

As Sweeney notes, ads linking a person’s name with criminal activity risk harming his or her reputation by suggesting wrongdoing when there is none. She asks readers to imagine that they’re being evaluated by a potential employer, who’s told to read up on their arrests when he or she searchers their name. “Worse,” writes Sweeney, “The ads don't appear for your competitors."

To test her hypothesis, Sweeney used existing research to find names considered either black- or white-identifying, then used those to compile more than 2,000 first and last name combinations belonging to real people. She queried those full names on Google.com and Reuters.com, both of which rely on Google’s AdSense for online ad delivery, and recorded the language of the sponsored posts that appeared. Her own name, for example, included an ad from InstantCheckmate.com that read, “Latanya Sweeney, Arrested?” and “Check Latanya Sweeney’s Arrests.”

On Reuters.com, a “black-identifying name was 25 percent more likely to get an ad suggestive of an arrest record,” Sweeney found. On Google, 92 percent of ads appearing next to black-identifying names suggested a criminal record, compared to 80 percent of white-identifying names. In fact, white individuals accounted for nearly seventy percent of all arrests and black individuals 28.4 percent of arrests, according to FBI crime statistics from 2011, the most recent year data is available.

Sweeney offers several potential explanations for the discriminatory ad copy. It may be that Instant Checkmate, which had the most online ads of any company tracked in the study, chose to link black-identifying names with ad templates suggesting a criminal record. However, Sweeney notes Instant Checkmate told her that it gave Google the same ad text to run with groups of last names, and did not vary ad templates according to first names.

In response to the study, a spokeswoman for Instant Checkmate said the company "would like to state unequivocally that it has never engaged in racial profiling in Google AdWords."

"We have absolutely no technology in place to even connect a name with a race and have never made any attempt to do so. The very idea is contrary to our company's most deeply held principles and values," the spokeswoman wrote in an email to HuffPost.

Google could be at fault, writes Sweeney, though a Google spokesman told The Huffington Post that the company does not target its users based on race, noting that advertisers are free to choose the terms against which their ads will appear.

“AdWords does not conduct any racial profiling,” the spokesman wrote in an email. “We also have an ‘anti’ and violence policy which states that we will not allow ads that advocate against an organization, person or group of people. It is up to individual advertisers to decide which keywords they want to choose to trigger their ads.”

It might also be that Google users are to blame: when an advertiser first chooses ad copy, all options are equally weighted and have an equal probability of being shown in the search results. Yet over time, as certain templates are clicked more frequently than others, Google will attempt to optimize its customer’s ad by more frequently showing the ad that garners the most clicks.

“Did Instant Checkmate provide ad templates suggestive of arrest disproportionately to black-identifying names?" Sweeney asks. "Or, did Instant Checkmate provide roughly the same templates evenly across racially associated names but society clicked ads suggestive of arrest more often for black identifying names?”

Some of the ad copy suggesting arrests that Sweeney had documented in her report did not appear when those names were queried by The Huffington Post, using Chrome's incognito mode, a week after her findings were released. In The Huffington Post's tests, searches for "Latonya Evans," "Latisha Smith" and "Lakisha Simmons" no longer displayed ads encouraging users to search their arrest record." However, Sweeney has told The Huffington Post that in her tests -- which involved navigating to Reuters.com, clearing the browser's cache and cookies and entering the names -- she found that the arrest language is still circulating in the ads.

"Online advertising is dynamic and easy to change, but as of today, ads suggestive of arrest continue to appear for names of real people even in cases where the company has no arrest record for the name in their database," wrote Sweeney in an email to The Huffington Post. "The best way to see these ads is to search for a name on a site that hosts Ads By Google, such as Reuters.com, one of the sites used in the study. You can view sample ads from the study on foreverdata.org."

This story has been updated with comments from an Instant Checkmate spokeswoman and a statement from Sweeney.