When President Barack Obama steps to the podium for Tuesday night's State of the Union address, nearly everyone expects him to lay out proposals to generate job growth.

But nearly everyone also expects Republicans in the House to oppose whatever the president proposes, citing the need to limit spending to close the federal budget deficit. It’s the dynamic that has ruled Washington for the last five years as both parties seek a response to the economic crisis: Should the government spend more money in the short-term to boost demand and reduce unemployment, or immediately tackle a budget deficit that until recently topped $1 trillion?

It seems at times as if the political debate has become divorced from the real-life needs of people.

"A lot of people out there in the real world are scratching their heads and wondering why Washington isn't doing more about jobs, as opposed to budget deficits," said Jared Bernstein, a former Obama administration economist who is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "I'm not saying it's easy, but that's the job of the leader: To explain to folks that we need to do both, and there's a sequencing to it."

Self-imposed deadlines such as the fiscal cliff and the so-called sequester at the end of this month, which would phase in $85 billion worth of cuts through September, have kept Congress laser-focused on the deficit. Obama's last major job-creation initiative, a $447-billion package introduced in September 2011, failed to overcome a Republican filibuster in the Senate.

But many economists argue that meaningful job creation must start with the types of programs put forth in that jobs bill -– for example, $175 billion in spending on new roads, modernizing public schools and community colleges and rehabilitating foreclosed homes and businesses.

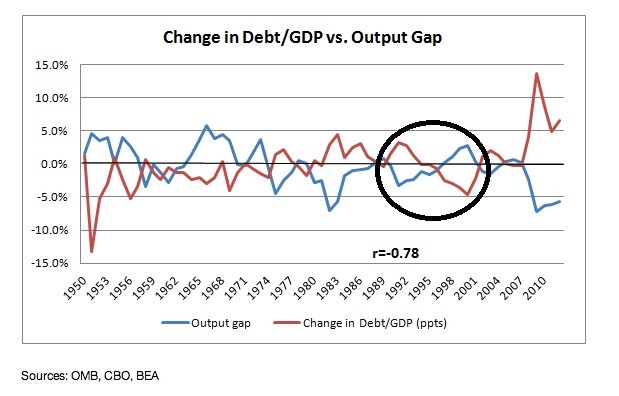

It's unlikely the dynamic in Congress will soon change. But economists point to the 1990s –- a time of rapid economic growth and declining budget deficits -– as an instructive example for the present. Deficits tend to decline after periods of economic growth, they argue.

Graphic courtesy of Jared Bernstein

"This idea that we're going to squeeze ourselves and in that way get a surplus -– you don't really find that in history," said Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. "We tend to think that cuts are painful, and therefore virtuous, like an athlete who endures pain. Well, cutting off your hand doesn't make you a good athlete."

Republicans have remained steadfast in pushing for deficit reduction. In a speech at the American Enterprise Institute last week, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-Va.) argued "there is no substitute for getting our fiscal house in order.

"There is no greater moral imperative than to reduce the mountain of debt facing us, our children and theirs," Cantor said. The agenda would focus on "creating the conditions for health, happiness and prosperity for more Americans and their families," and to "restrain Washington from interfering in those pursuits."

Other economists argue that months of budget brinkmanship came after Obama lost control of the message on how to best promote economic recovery.

"The president has not tried very hard, and I think he has been part of the problem," said Ross Eisenbrey, vice president of the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning Washington think tank. "He has given too much credence to the notion that we have to do something about the deficit now. Economically, that's completely wrong. The crisis in unemployment is a catastrophe for these families."

Economist Justin Wolfers, now at the University of Michigan, wrote in a blog last summer that he had "never seen the disjunction between the political debate about economics and the consensus of economists be as large as it is today." The disjunction, he wrote, "is incredibly damaging."

Economists said the debate needs to shift toward measures that will produce demand for jobs in the short term, leaving deficits for after unemployment is addressed.

Republicans have panned Obama's 2009 economic stimulus. Economists, however, generally agree that the plan successfully reduced unemployment. More than 90 percent of economists polled by the University of Chicago said the unemployment rate at the end of 2010 was lower because of the stimulus. More than half believed the benefit exceeded the cost, according to the poll.

"The fact is that temporary employment measures, ones that get into the system and get out, don't hurt you on the deficit," said Bernstein, of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. "There's nothing inconsistent with a plan that would help create jobs in 2013 and 2014, and then get out of the way."