MIAMI -- Halfway through megapastor Joel Osteen’s sermon at Marlins Park stadium, seven frazzled people sitting in a press box overlooking the field realize they have a problem: The prayers aren’t going through.

“I can forward ‘prayer’ to ‘prayer request,’” volunteers a member of Osteen’s technical staff as a possible fix. He fiddles with the trackball of his BlackBerry as he tries his best to reassure Osteen’s marketing director, Jason Madding, that they can redirect people's emailed prayers to the proper place and prevent them from disappearing into the digital ether.

Hunched over a MacBook, Madding flips back and forth between a Skype chat and a page tracking traffic to Osteen’s sites. He coordinates with a remote team of developers as he monitors the popularity of Osteen's page to gauge whether the surge of visitors will overwhelm the servers and bring down the site.

On the field below, a musician blows two long blasts from a ram’s horn while drums thump in the background. “Every day has your name on it,” Osteen shouts to the crowd.

Osteen, a 50-year-old Texas native with an impeccable complexion, thick head of dark hair and a gleaming white smile, is the pastor of the largest church in America. On this April night in Miami, nearly 36,000 cheering people have gathered in the stands of the stadium to hear him speak. But for Madding, the crucial action is playing out on an iPad propped on a desk in front of him: He is watching the live stream of the pastor’s sermon as it appears to audiences who are tuning in from home -- a group numbering more than 138,000. They are absorbing Osteen’s “Night of Hope,” a gathering of evangelical Christians aimed at strengthening people's commitment to Christ, swaying non-believers and spreading Osteen's message of self-improvement through Christianity.

Madding’s iPad displays a ceaseless stream of comments from those taking part from their homes around the world -- people grappling with illness, joblessness, loneliness, despair and suicidal thoughts; people seeking comfort, prayer and fellowship here. These participants are not inside the stadium, but in an expanded gathering that connects the experience of those here in the flesh with those online.

Over the course of this night, Osteen’s team of social media consultants confronts the formidable task of making that synergy happen. They struggle to keep up with the relentless flood of digital interaction. In life, prayers may or may not be realized. But in the social media realm of the Night of Hope, all prayers must be answered.

Osteen's staff has instructed online congregants to post prayers to his Web site or phone prayers to a 1-800 number. They've also provided an email address -- prayer@joelosteen.com -- assuring digital participants that the church has dedicated prayer partners on hand who will field their missives and pray for them.

But at this moment, those emailed entreaties have no prayer of reaching anyone. The email address Osteen's helpers have supplied is the wrong one. It's an address that doesn't exist -- the staff was meant to offer up "prayerrequest@joelosteen.com." Thanks to the error, an automatically generated email reply is informing the faithful that delivery of their prayers has "failed permanently."

“It bounced back,” types one of the people in the chat room, who has tried to email from her home in Canada. “I need your prayers.”

She tersely summarizes her feelings about the situation: “=(.”

A man prays at the Night Of Hope in Miami.

A man prays at the Night Of Hope in Miami.

THE ORIGINAL SOCIAL MEDIA

Social networking sites, long celebrated as avenues for up-to-the-minute information from friends, pundits, celebrities and corporations, are now being deployed in the spirit of higher powers. They have emerged as vehicles for spiritual salvation.

Increasingly, the road to Damascus is a hyperlink and the Epistle is a tweet. In some sense, this seems inevitable. The Internet is effectively doing for present-day pastors what television once did for Jerry Falwell, Jimmy Swaggart and the rest of the so-called televangelists: helping them spread Christianity on a mass scale while liberating their congregations from the confines of the physical church.

Beyond the tens of millions of viewers who can be reached via television broadcasts, the Web has amplified the potential audience to the hundreds of millions, while transcending geographic boundaries. Pastors need not concern themselves with buying TV time in the appropriate markets. They can instead use tweets, streaming video, podcasts and Facebook status updates -- free, accessible anytime and widely shared -- to turn hearts and shepherd their flock. And while TV is a one-way form of communication, the Internet enables interaction, letting ministries converse with the people tuning in.

“Thirty years ago, televangelists used technology that did not exist before then to spread their message, and that is essentially what technology is allowing pastors and churches to do now,” said Todd Rhoades, the director of new media and technologies at the Leadership Network, which seeks to help churches master technical innovation. “But it’s on a much larger scale and in many ways it’s on a more individual scale -- it seems a lot more personal.”

Osteen during a 2012 interview with Matt Lauer on NBC News' Today show. (Photo by: Peter Kramer/NBC/NBC NewsWire via Getty Images)

Osteen during a 2012 interview with Matt Lauer on NBC News' Today show. (Photo by: Peter Kramer/NBC/NBC NewsWire via Getty Images)

Social media brand managers would pay dearly for fans as active as the followers that religious groups have attracted online. On social networking sites, megapastors’ fan bases are considerably smaller than those of pop stars or big brands, but church followers tend to be far more engaged and apt to spread the word of their preachers.

Religious groups regularly rank among the top five most-discussed fan pages on Facebook, according to PageData, a social media analytics firm. Rihanna, the most popular public figure on Facebook with over 70 million “likes,” averaged 41,000 interactions per Facebook post during the month of March, reported Quintly, an analytics firm that registers shares, comments and “likes” as individual interactions. Joel Osteen Ministries, with a relatively paltry 3.6 million “likes,” averaged 160,000 interactions per post, Quintly found -- nearly four times Rihanna’s average, three times Justin Bieber’s and almost sixteen times the White House’s.

Evangelical Christians and social media creators ultimately share something fundamental in common: Both are consumed with the nature of how information spreads, and both are intent on fashioning a sense of community out of individuals separated by time, space, language and culture. Both also passionately apply themselves to filling what they view as a void in the human experience.

“Religion is the original social media,” says Jonah Berger, author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On. “Even that phrase, ‘spreading the gospel.’ Religion is one of the original things that people shared to a good degree.”

'THE DIGIVANGELIST'

Osteen has long harbored aspirations of reaching enormous numbers of people. Early in his career, when he published his first book, Osteen's public relations team pitched him as “Billy Graham meets Tony Robbins.” His message of positive thinking and attaining personal prosperity through Christianity has attracted both devout followers and strident critics, who argue he preaches a watered down version of the Bible that overemphasizes material wealth. But his breed of self-empowerment evangelicalism -- “Be a victor, not a victim,” “[God] wants us to enjoy every single day of our lives” -- has proved so popular, Osteen delivers his song-filled sermons to traveling Night of Hope events held monthly in different cities around the world. He’s also authored several bestsellers and reaches 10 million homes a month via his weekly TV broadcast. He has a passion for television and doesn’t seem to have ever met a camera he didn't like. “TV is Joel’s heart,” notes Madding.

But seeing new opportunities to expand his following and spread his brand of inspiration, Osteen has lately sought to master a new field: digi-vangelism.

In his telling, social media enables him to “impact more people in a positive way” -- an impact he no doubt hopes will ultimately tether believers and non-believers closer to his congregation (and maybe even sell some of his books or DVDs along the way).

Other churches, like Oklahoma’s evangelical LifeChurch, have been more ambitious and creative with their approaches to technology, though none can yet rival Osteen’s reach.

And Osteen, born in an era where the dominant screen was a television, not a computer, is facing some of the same challenges other churches are confronting as he attempts to update his message for the Facebook era. Larger churches have traditionally been technology’s early adopters, and smaller congregations are likely to crib from Osteen’s social media strategy.

Here’s where devotees can currently find Osteen online: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, on podcasts, delivered to their email inboxes, as a blog on JoelOsteen.com, livestreamed via his website, in an iPad magazine and, coming soon, on two standalone iPhone apps. To handle the deluge of prayer requests posted to Osteen’s Facebook wall and phoned into his church, Joel Osteen Ministries has even launched a dedicated site, Pray Together, where people can post prayer requests for the ministry’s entire congregation to respond to. Just click “pray” to pray.

“It’s kind of like -- are you familiar with Reddit or Digg?” asks Brian Boyd, the chief executive of Media Connect Partners (or MCP), a social media consultancy that assists Joel Osteen Ministries with their with day-to-day online outreach efforts, as well as their Night of Hope events. “You can vote a prayer request up or down, and actually pray.”

Some evangelical Christians view these developments with alarm, decrying what they portray as an insincere reach for souls with social media and a trend that could undermine the draw of in-person gatherings of people in one place. Evangelical Christian pastor John MacArthur railed against “flat screen preachers” in a 2011 interview with Christianity.com, declaring their form of ministry an “aberration” that moved “away from the core of sound doctrine.” But Osteen’s social media consultants maintain they have witnessed the faithful finding real fellowship and solace in a virtual setting.

“You don’t have to sign up for an email, you don’t have to go to church, and you don’t have to go out and find it: you can literally log onto your computer or your phone, and you can get the encouragement or inspiration that you need,” says Kelly Vo, a twenty-something social media analyst manager with MCP who helps Osteen, along with other Christian figures, on his web strategy. “People share things on social media, with Joel, that I don’t think people would even share with their pastor in person.”

'I SPEAK JOEL'

It's just after noon on Saturday, more than six hours before the Night of Hope is set to begin, and already a gaggle of web gurus have arranged themselves at a long desk in the empty press box at Marlins Park. They are seated elbow-to-elbow, MacBook-to-MacBook, as they prepare for the intense activity ahead. The room is silent, save for the growl of planes flying overhead and the occasional twang from an electric guitarist rehearsing on the black stage below.

For the Night of Hope, Boyd's MCP has rallied a team of 10 to run social media, with most of the moderators here in Miami and others working from their homes scattered from Las Vegas to Charlotte. Joel Osteen Ministries has tapped another 11 people, including Madding's marketing staff and a group of developers, to be sure Osteen's site doesn't collapse under the weight of its online congregation. In Texas, Osteen has seven prayer partners, made up of Lakewood Church staff and volunteers, on hand to pray via email and on the phone.

The mission for this sizable social media operation is to transpose and transmit the real-life experience of Osteen’s Night of Hope sermon -- a rock concert-like production where thousands pray, sing, shout, stand, stomp, hug, clap, cry and convert -- to people sitting alone, in darkened rooms, before the glow of computer screen.

“I want it to be real, interactive,” says Boyd. “I want them to feel like they’re sitting in the stadium.”

MCP will update Joel Osteen Ministries’ social accounts throughout the night in an effort to drive people to the main attraction: the live, online video stream of the Night of Hope and the public chat room that sits alongside it on the screen. Osteen's chat room will be open to all comers as a place where they can message with other followers or with the team of MCP moderators on hand to offer encouragement, share information on local churches and answer questions posed by the virtual attendees. A separate section of the screen will allow participants to post prayer requests for all to see and answer.

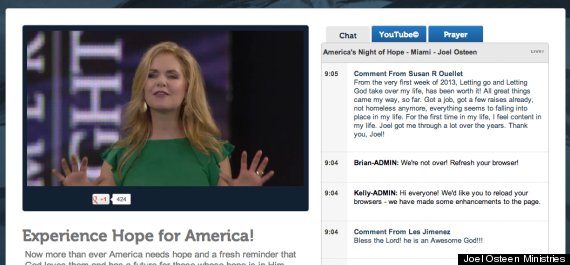

Osteen's wife, Victoria Osteen, as seen during the Night of Hope live stream on Osteen's site the night of the event.

Osteen's wife, Victoria Osteen, as seen during the Night of Hope live stream on Osteen's site the night of the event.

Vo, a slim brunette dressed in purple pants, a lavender collared shirt, and black pumps, works on putting together a list of pastors to follow on Twitter. Peering into her laptop, she shifts between Twitter, Facebook, a custom-made scheduler listing outgoing posts and the Instagram app on her iPhone.

Though this is Vo’s first Night of Hope, she has worked smaller Osteen events, and she has a sense of what’s in store. She has warned her colleague to steel himself for a virtual stampede.

“There are thousands of comments a second,” she tells another team member. “It’s just a massive undertaking. It’s exciting because his fans are excited, and so nice, and they’re so happy to be a part of it and they’re so enthusiastic.”

That deluge of comments is the most stressful part of the night for Boyd, who notes it's simply impossible to interact personally with every virtual attendee -- though that's the aim.

"We really do want to try to reach everyone," he explains. "If someone asks a question, we want to get an answer to them. If someone has a concern or wants to give a praise report, we want to be able to talk to them, and you just can’t do it. Even with 10 people, with that kind of volume, you're unable to get to every single person."

A former literary editor who studied creative writing at Arizona State University, Vo knows Osteen’s fans better than most. She’s helped manage Osteen’s social profiles for six months, and spends an hour or two every day responding to his followers’ comments or drafting status updates to send from the pastor’s accounts. The posts, based on lines from Osteen’s sermons and books, are each screened by Joel Osteen Ministries’ media relations chief, Andrea Davis, before they're published. Osteen is against personal updates and insists on short, motivational phrases: "It's hope, it's inspiration, it's stuff that they can use," the pastor explains. "That has helped us be effective." Though Osteen doesn’t tweet himself, he has a separate, private Twitter account from which he monitors his official feed. If Osteen sees a tweet go out that doesn’t sound true to him, Davis can expect a call.

“I eat, breathe and sleep Joel at times,” says Vo. “I speak Joel now … You pick up the voice and it’s like, ‘Oh, God bless you’ and ‘Would love to pray for you.’”

And yet, much like the majority of the congregants who will gather here tonight via social media, Vo knows Osteen primarily as a digital experience: She has met him in person only once -- the day before.

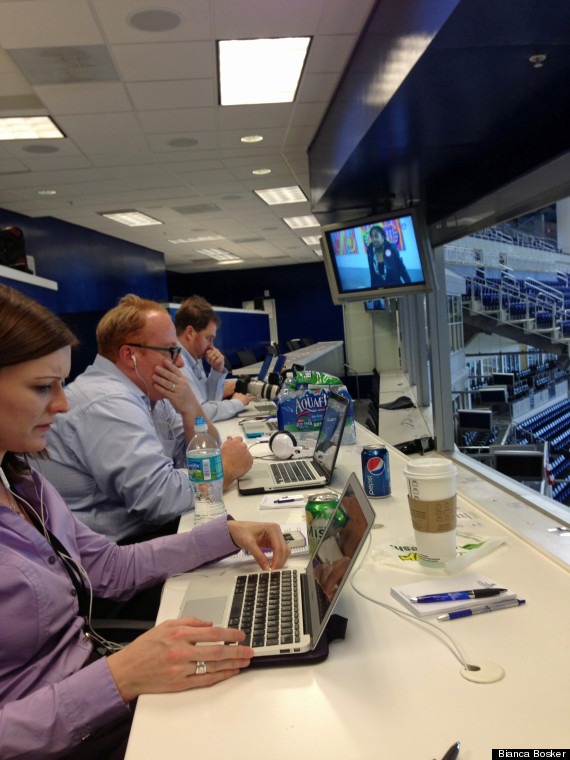

The MCP Web moderators in the Marlins Park press box, dubbed "Social Central JOM" (short for "Joel Osteen Ministries").

The MCP Web moderators in the Marlins Park press box, dubbed "Social Central JOM" (short for "Joel Osteen Ministries").

Osteen's Facebook and Twitter posts are relatively standard fare, but their reception is anything but typical. A tweet sent earlier that morning advised his 1.6 million followers, “Today, find something to be grateful for. Every day is a gift from God.” That message has been retweeted over 6,000 times, about average for Osteen, who takes a personal interest in his retweets. By contrast, Whole Foods, which boasts twice as many followers as Osteen and in 2012 was named the most influential brand on Twitter, is lucky to see one of its tweets retweeted a dozen times.

Retweeting and "liking" on Facebook amount to an effective way to convey the Word, as believers disseminate Osteen’s message through their genuine social networks.

“It opens up the doors for a lot of unbelievers,” says Alisha Brooks, one of the in-person attendees at the Night of Hope who follows Osteen closely online. “Through social media, I might have a whole bunch of people who follow me that may not be into the Word or anything like that. So if I see something [Osteen] tweets and I retweet it, now it has access to an extra 100, 200 or 300 people that didn’t have access to that or didn’t see it. And it might help.”

Vo breaks from her Twitter work to scan through the 400-odd comments on Osteen’s most recent Facebook post, systematically “liking” some and answering questions about the Night of Hope. That personal attention, says Vo, helps endear Joel to people by assuring them he’s hearing their prayers and praise -- even if it’s from the “JOM Team,” not Osteen himself.

“Joel is there. He’s touchable, he’s interactive. You don’t feel like he’s just a TV,” she says. “The followers know he’s there, he’s listening, he’s a pastor and he’s watching, so they get the interaction.”

'I NEED A PRAYER'

About twenty minutes before the Night of Hope is scheduled to begin, Vo resettles herself in front of her computer. In addition to updating Facebook and Twitter, she’s been assigned the role of “greeter,” meaning she will be welcoming people to the Night of Hope chat room. So-called "URL pushers" will answer queries with pre-written blocks of text that direct people to everything from Osteen’s Twitter account to local churches. Two others from the group will screen each incoming comment before publishing it to the public forum, and someone else will run giveaways (the prizes: free copies of Osteen’s books)

In the Night of Hope chat room, people waiting for Osteen to take the stage banter about where they’re from and where they’re watching the stream: Israel, Canada, Hawaii, North Carolina. Shortly after 7 p.m., Osteen’s big, pearly grin flashes onto the screen.

Prayer requests begin to flow into the chat room. Elsewhere on the Internet, people tend to present themselves in the best light. Here, people bare all, sharing stories about depression and abuse, seizures and strokes, infertility and lost children.

“Hey everyone I need prayer,” writes a woman, who identifies herself in the chat as “Lisa Elliott.” “I am dealing with Brain Cancer and dealing with abuse in my life and asking for some prayers in this I feel like I cant keep going with the way my life is going.”

Vo writes back to Elliott assuring her Osteen ministries "would love to stand with you in prayer." She advises her to share her prayer request online, or by phoning into a 1-800 line, where volunteer prayer partners will join callers in prayer and offer them scripture.

Then, 30 minutes later:

8:05 p.m. Comment From Lisa Elliott: siting here in tears

8:14 p.m. Comment From Lisa Elliott: I hatmy life my abusive boy friend is drunk sleeping if he wakes up I get beat

“Lisa, We are standing with you during this time,” types one of the moderators, called “Matt-ADMIN.” He directs Elliott to a prayer site and to the erroneous email address, prayer@joelosteen.com. “Our prayer team would love to pray with you.”

Another woman in the chat room, someone not part of the Osteen team, tells Elliott: “my prayers are with you, I was in your situation nine yrs ago, there is a way to get help, call your local womans help center as I did.”

“Can I have the number so I can call them now,” Elliott asks. Then, “crying over this I have never had something like this.”

“Enjoy the experience, Lisa!” a moderator answers cheerily.

Another half hour passes.

9:00 p.m. Comment From Lisa Elliott: please pray for me toight that nothig happens9:00 p.m. Comment From Kelly-ADMIN: Lisa, we are standing with you in prayer and faith.

9:03 p.m. Comment From Lisa Elliott: I know he will beat me tonight

Another moderator is congratulating Elliott. Apparently, she has just won a free copy of Osteen’s newest book.

The MCP team is having trouble keeping up. The room grows quiet, save for the frantic tap of fingers clicking on keys. An unpublished queue of comments speaks to the agitation of people waiting for answers: “CAN YOU SEE ME???” one person has typed. A moderator sends a private message to a particularly frustrated user, assuring him they’re doing their best.

As tens of thousands of people absorb the live stream, the video is stalling, spurring even more gripes in the chat room and on Osteen’s Facebook wall.

“You’ve got thirty complaints on your Facebook page that the servers are down,” the wife of one of Osteen’s photographers informs Vo.

Vo clenches her jaw. The audience is diminishing, with the number of concurrent online viewers down to 34,000 from over 41,000 earlier in the night. People have spent an average of 48 minutes watching the Night of Hope, but the video's hiccups seem to be costing Osteen his viewers. Boyd tells Vo to post a link to the live stream on Facebook. Now.

“It’s frozen, my thing is frozen,” Vo answers through gritted teeth. “It’s literally frozen.”

A view of the Marlins Park stadium on the Night of Hope.

A view of the Marlins Park stadium on the Night of Hope.

In Rapid City, South Dakota, Janice Heigh, 53, logs on to the chat room to seek help. She and her husband have been overwhelmed by the work of caring for their three grandchildren. She feels distance and isolation seeping into her marriage.

She also feels removed from a community of people grappling with similar troubles. Though she attends weekly services and teaches Sunday school at a local Rapid City church, Heigh has struggled to find a Bible studies group for people in her predicament. There are meetings for parents with young children -- populated by people decades her junior -- and meetings for people in her age group, who generally have other worries. She has had trouble arranging her schedule around that of her local church.

But on the Web, church services are always happening, and support groups are to be found at every hour of the day. Heigh has tapped into them via Facebook, Prayer.com, and at sites like the one for Osteen’s Night of Hope. In this way, she has found other grandparents tending to their own grandchildren. She has taken comfort in seeing that other people’s lives are imperfect, too. Unlike in person, these online exchanges spare Heigh from feeling like she's a burden: The people she chats with online are there because they want to be. She takes refuge in the anonymity of this interaction.

“At midnight, I can go to the computer, pull it up and there’s someone on there somewhere who can give you insights, a kind word,” she says. “They’re thinking about you, praying about it and it’s like, ‘I’m OK. I’m all right. It broadened my horizons spiritually because I was able to feel connected, even though I knew there was no way I could make it to this or that.”

On this night, in the chat room at the Night of Hope, she begins typing.

“Iwill be maried 34years tomorrow," she writes. "My husband and I have had many years of trials and triumphs. We are now raising our daughters 2 girls. I feel that my husband and I have grown far apart since we took on the resposibility of these GOD given children."

“Please pray that we can come together after all these years.” Heigh continues. “We have had the girls for 7 years so it is not a new situation but seems I am a single parent.”

Vo answers a minute later.

“Janice, thank you for sharing your story and your heart with us,” she types back. “We are standing with you in prayer and faith. May God's goodness and mercy shine upon you.”

From Miami to South Dakota, this message makes its way, arriving with the affirmation intended.

“It makes you feel validated,” Heigh explains later. “The Internet, to me, it has brought a whole situation to God.”

This story appears in the Issue 52 of our weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, in the iTunes App store, available Friday, June 7.