Did you know Miami has a mom? It's true!

Julia DeForest Tuttle, the "Mother of Miami," is widely recognized as the only female founder of a major American city. The visionary widow from Ohio bought hundreds of acres at what is now Downtown Miami, moved down on a barge, and eventually convinced railroad man Henry Flagler to extend his new railway to the Miami River by sending him an unusual package.

"It may seem strange to you," she told a friend, "but it is the dream of my life to see this wilderness turned into a prosperous country."

"She believed that the area would become a great city, one that would become a center of trade for the United State with South America," according to the National Women's History Museum. (She also reportedly outlawed liquor sales in city limits, but no one's perfect.)

Mrs. Tuttle's visionary deal, however, didn't come cheap -- and she had some strong motivations of her own. To find out how a widow from Cleveland wound up creating the Magic City, check our Mother's Day salute to Mrs. Tuttle below:

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

South Florida was one of America's last frontiers just over 100 years ago. In the late 1890s there were fewer than 1,000 people living in Dade County, which stretched from the upper Keys all the way to Jupiter Inlet, north of Palm Beach.

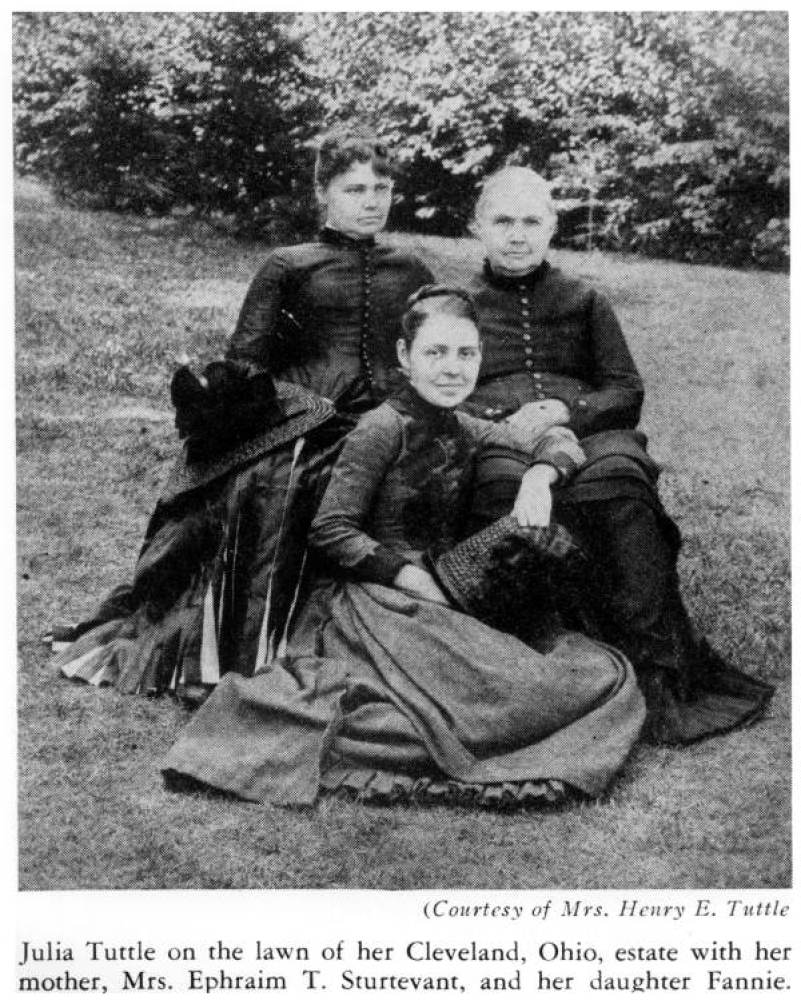

Julia Tuttle first laid eyes on what would become Miami as early as 1874 while visiting her father -- who had moved to the Lemon City area as a homesteader and become a county judge and state senator -- but returned to her husband and family in Cleveland. She had arrived by steamship, and liked what she saw.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

In 1886, Julia's husband Frederick Leonard Tuttle died, leaving her his iron foundry to operate.

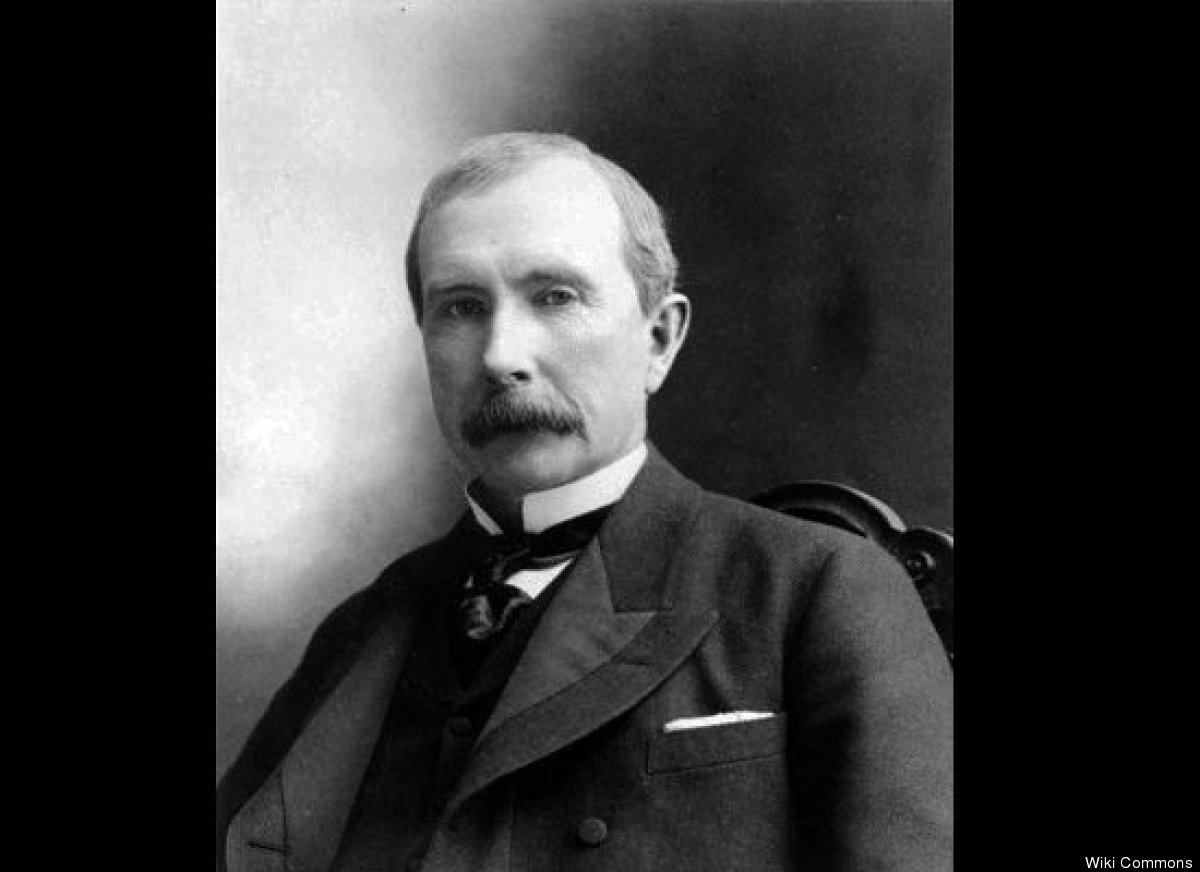

"I shall need to do something to increase my income somewhat and I have been thinking of getting something to do for a part of the year in a more genial climate," she wrote to her longtime friend from Cleveland, Standard Oil industrialist John D. Rockefeller. "...I could not do what would confine me constantly indoors or at a desk."

She also told Rockefeller that her daughter Fannie was "not quite as well as I wish she was" and thought a "milder climate" would help.

Wikimedia Commons

Julia's father-in-law had been Rockefeller's first boss, and she and Rockefeller (above) had attended a Baptist church together for years in Cleveland. One of his Standard Oil partners was railroad magnate Henry Flagler, who was extending his tracks down the east coast of Florida and developing towns and hotels along the way.

Julia, an obvious go-getter, wrote Rockefeller to ask for a favor:

Now if you think I am equal to such an undertaking I think I would like the position of housekeeper with the new hotel Mr. Flagler is building at St. Augustine and if you would be good enough to recommend me to Mr. Flagler I am sure your good word would do much to induce him to give me a trial... Of course you may not think this is a feasible project at all, but you can easily say so. As I understand it the building will not be completed until next season but I thought if one was going to get the position it was time to be moving in the matter.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

Rockefeller did indeed meet with Flagler and ask about the job, but fortunately for Miami it seemed the position had already been filled by the hotel's manager. But as historian Edward N. Akin writes, her letters indicate Tuttle was by then very much intrigued with investing in Florida.

"I think Fla. will become my headquarters," she wrote Rockefeller two years later, in 1888.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

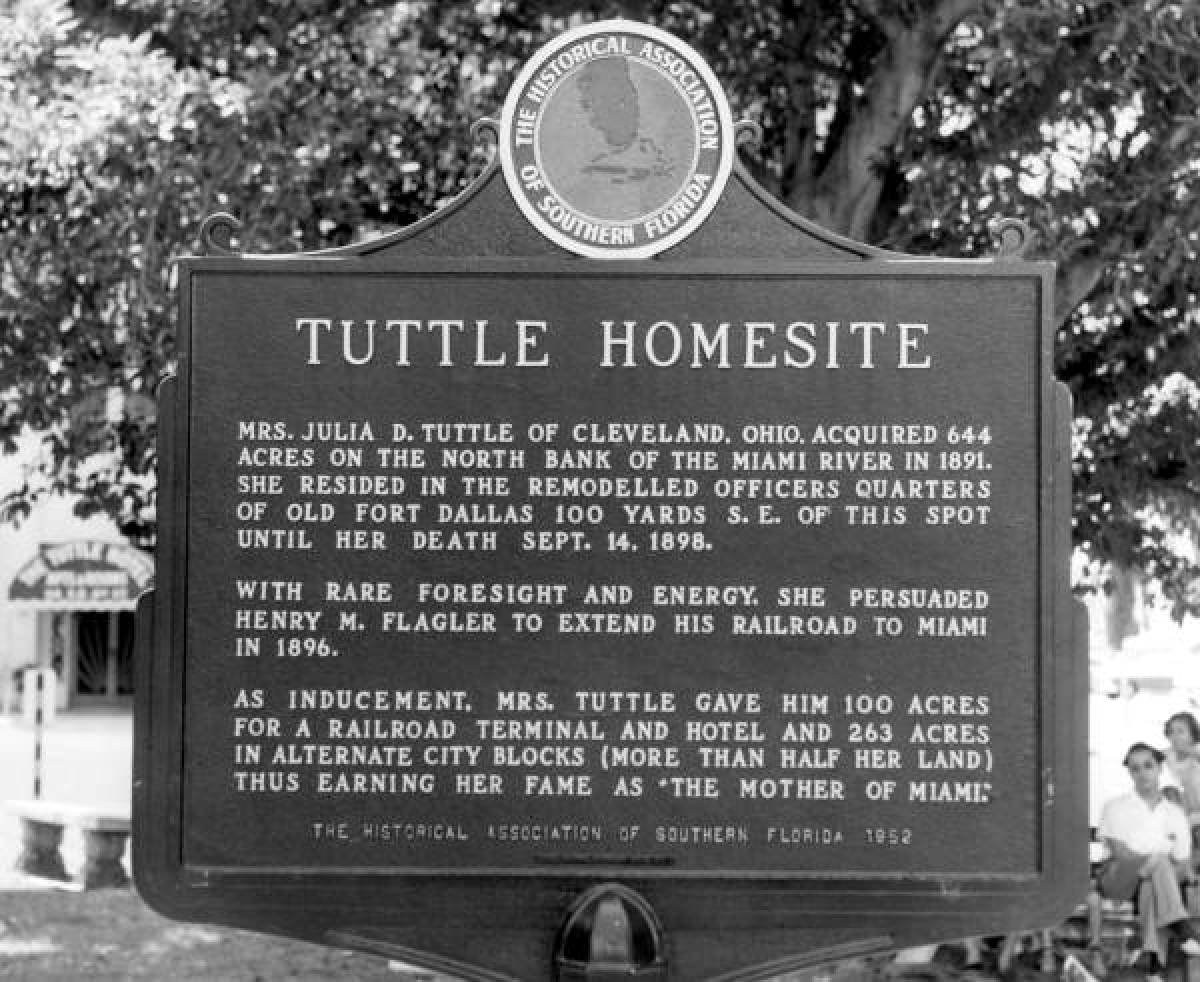

When Tuttle's father died and left her his Florida land in 1891, she permanently moved to the shores of Biscayne Bay. Her neighbors across the river were William and Mary Brickell, fellow early and influential pioneers. She purchased some 640 acres of land including Fort Dallas, a military installation from the Seminole Wars on the north bank of the Miami River, and moved right in.

In the photo above, Fort Dallas' barracks are on the left, and two stone buildings known as officers' quarters are on the right. According to the State Archives of Florida, Julia Tuttle occupied these buildings as her home in November 1891.

Think Mrs. Tuttle chose her site well? This is the mouth of the Miami River today.

Getty Images

From Gene M. Burnett's book "Florida's Past: People and Events That Shaped the State:"

Speaking in the 1950s, an aging [Miami pioneer banker] J.E. Lummus recalled the time he visited her and asked her point blank, "Do you really think this place has a future?" She replied, "Mr. Lummus, if you live your natural lifetime you will see one hundred thousand people in this city." He did see them, many times over. It was a visionary's understatement.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

Another view of quarters at Fort Dallas remodeled into a home by Julia Tuttle.

"She arrived with her adult children, furniture and cows by barge, cutting through the dense brush to land," according to Coral Gables Memory.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

The Miami Hotel "was the city's first hotel," according to the State Archives of Florida. "It was built by Julia Tuttle as a bunkhouse. She had the building jacked up, set on a brick foundation and enlarged. It burned down in 1899."

Tuttle had realized the area would never prosper unless it was reached by the railroads, and began an aggressive campaign to convince Henry Flagler to continue his tracks to Fort Dallas -- even offering to give up hundreds of acres of her land.

Above: men on the porch of Julia Tuttle's hotel, 1896. State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

Tuttle first tried convincing transportation mogul Henry B. Plant to bring trains to Miami from his railroad's terminus in Tampa, but after the firm conducted a study they deemed it impractical.

Neither did she have any luck convincing Flagler to extend his railroad via letters, and even paid a fruitless visit to the magnate in person in St. Augustine. But nature stepped in to help: the three Great Freezes of 1894-1895 devastated orange groves and vegetable farms in central and northern Florida, wiping out citrus and fortunes alike.

When Tuttle smartly sent Flagler a package of flowers or foliage -- some say it was fragrant and enticing orange blossoms -- she proved her Miami River properties were below the frost line. Flager, unhappy to see settlers moving back north and his fruit shipping business dwindle, recognizing the obvious financial opportunities and gave in. He agreed to lay 60 miles of track to Miami from his railroad's end in Palm Beach.

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

For Julia, who convinced neighbors Mary and William Brickell to also throw acreage at Flagler, the deal didn't come cheap. The railroad man agreed to build a large hotel and lay the foundations of a city on either side of the Miami River in exchange for splitting the rest of her 640 acres.

The first train entered Miami on April 13, 1896. In a month of the its arrival -- with a mail coach, baggage car, day coaches and a chair car -- Miami had its first newspaper, the Miami Metropolis, and bank, The Bank of Bay Biscayne, up and running.

Miami was officially incorporated as a city in a pool hall meeting days later on July 28, 1896. Its first laundry, first bakery and the first dairy were reportedly started by Mrs. Tuttle.

Wikimedia Commons

When it opened in January 1897, Flagler's Royal Palm Hotel became a popular resort for Gilded Age bluebloods including Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and the Vanderbilt family.

"She is at the very moment of ensuring the foundation of the city by offering Henry Flagler proof that orange blossoms grow here and were not destroyed in the freezes," said sculptor Rob Firmin, who created the above likeness of Tuttle in Miami's Bayfront Park. "She is looking to the future."

State Archives of Florida/FloridaMemory.com

In dedicating a plaque to Julia Tuttle in 1952, U.S. Senator Scott M. Loftin reportedly pointed out that

such astute and far-sighted business men as John Egan, Richard Fitzpatrick, William F. English, Dr. J. V. Harris and members of the Biscayne Bay Company had purchased one after another the property on which Miami now stands, yet failed to realize that they held the site of a future city in their hands.

"It remained," said the senator, "for a wise and remarkable woman to envision its possibilities."

Mrs. Tuttle died two years later on September 14, 1898, at age 49. Her name adorns the Julia Tuttle Causeway of Interstate 195 to Miami Beach, and her statue remains in Bayfront Park near the children's playground.

"Flagler had the money, but Julia Tuttle got the push," said Mariano Cruz, a mail carrier who attended the statue's unveiling in 2010. "Had it not been for her, Miami would still be the alligators playing in the swamp."

According to History Miami, there were nearly 1,000 subdivisions under construction in the Miami area by 1925.