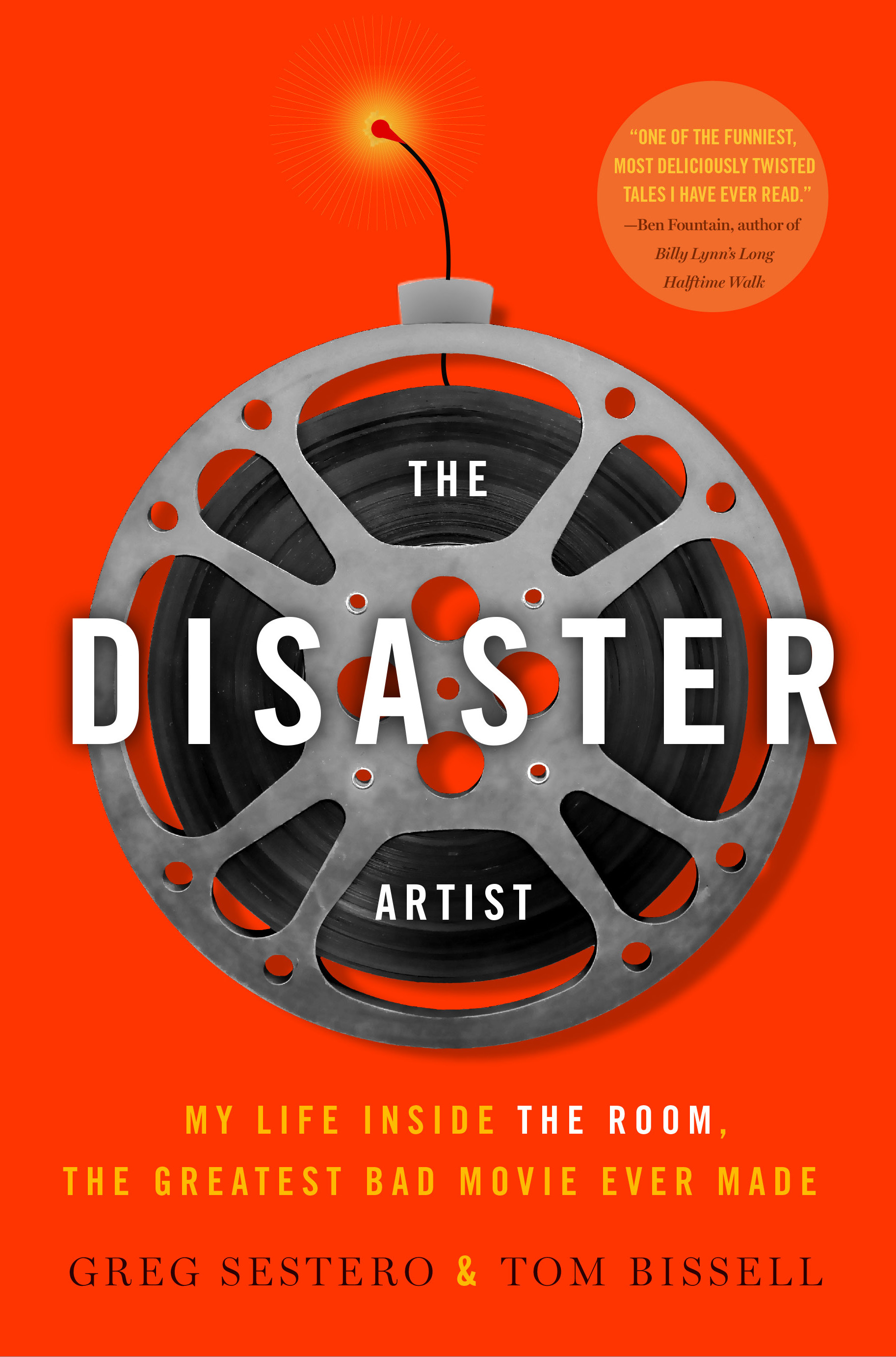

The book we've all been waiting for was released this week. Thanks to Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell, all of our "The Room" questions will finally be answered. Below, enjoy an excerpt where Sestero details the grueling three hours and thirty-two takes it took to get Tommy Wiseau's infamous entrance onto the rooftop. He did not hit her, he did nawwwwwt.

You can purchase The Disaster Artist here.

We filmed the first part of Tommy’s and my scene—Johnny making his dramatic entrance onto the Rooftop—last. To shoot him doing this, the crew had to rearrange the Rooftop walls and push into place the tiny, tin-roofed outhouse that was doubling as the Rooftop’s access door.

Since the outhouse was so small, there was no room inside to cre- ate the illusion of continued movement. This meant that anyone being filmed exiting it had to stand perfectly still while waiting until action was called. Coming out of that thing, you stumbled into your scene.

In the original draft of the Room script, the stage direction reads: “JOHNNY OPENS THE DOOR TO THE ROOF ACCESS. MARK IS SITTING THERE.” Tommy had decided this wasn’t dramatic or emotional enough, especially now that he’d rewritten his script to include scenes in which Lisa claims to others that Johnny has abused her. To establish that Johnny is incapable of abuse, Tommy con- cocted a new opening for this scene, in which Johnny steps onto the Rooftop saying, “It’s not true! I did not hit her! It’s bullshit! I did not.” After which comes this: “Oh, hi, Mark.” There are seventeen words in this sequence. Eleven of them are nonrecurring; only one carries the burden of a second syllable. In other words, these are not terribly dif- ficult lines to learn.

Sandy had blocked the scene so that Tommy would emerge from the outhouse; hit his mark on the second “I did not”; look up; nail his eyeline; say, “Oh, hi, Mark”; and walk off camera to where we, the audience, imagine Mark to be sitting. Most school plays contain scenes that pose bigger technical acting challenges.

Tommy couldn’t remember his lines. He couldn’t hit his mark. He couldn’t say “Mark.” He couldn’t walk. He couldn’t find his eye- line. He would emerge from the outhouse mumbling, lost, and dis- oriented. He looked directly into the camera. He swore. He exploded at a crew member for farting: “Please don’t do this ridiculous stuff. It’s disgusting like hell.” Sandy stood there so openmouthed that it looked as if he were waiting for someone to lob something nutritive at him.

Finally Tommy commanded me to sit off camera, hoping that my becoming his living eye line would help him. It didn’t. Everything be- came infectiously not-funny funny. People were turning away from the set, their faces constipated with laughter they dared not release. Tommy didn’t notice any of this. He was locked into a scene and a moment he couldn’t bring to life. It was as horrifyingly transfixing as watching a baby crawl across the 405 freeway. We were all waiting for a miracle.

It took Tommy thirty minutes to feel comfortable enough to walk down the outhouse’s two steps without staring at his feet. It took an- other thirty minutes for him to take those two steps while also remem- bering his lines. With time, and effort, he got the walking-talking aspect of the performance down, but doing all this while hitting his mark and looking at me remained a grand fantasy. Sandy kept saying, “Now you need to look up when you say hi to Mark.” Tommy would nod. Yes. In- deed. Exactly what he needed to do. He would try, and try again.

Tommy/Johnny: “I did not.” Sandy: “Look up!” Tommy/Johnny: “Oh, hi, Mark.”

Sandy: “Up! Up!”

Sandy stopped everything and took Tommy aside. He tried to reason with him, as though Tommy’s understanding and not Tommy’s ability were the real problem. “You have to look at Mark when you say the line, okay? Because right now you’re looking down.”

“Okay,” Tommy said.

He’d rehearsed this moment for half the day and this was the result. Soon the cameraman was laughing so hard that his camera started to shake during takes.

Sandy decided to watch some VHS playbacks, to see if there was anything—anything at all—usable. I was still sitting off camera, feel- ing as though I’d been dosed with something potent. Tommy came over to me, looking worried. “How am I doing?” he asked. “Give me the feedback. Something.”

It was a genuine request. I felt sorry for him at that moment. I knew how hard he was trying. I also knew that being a dramatic actor was the most important thing to Tommy. Everything he’d done in life was to get to this point. How could I help him? I had no idea.

“You’re doing great,” I said.

But the obvious peril Tommy was in—that the whole production was now in—had broken through his vanity. For once Tommy wanted something more than chummy assurance. “How,” Tommy asked again, more insistently, “am I doing? Don’t pull my legs!”

I looked around, thinking, Props, because props always helped Tommy; they took his mind off trying to act. I saw a nearby water bottle and grabbed it. “Here,” I said, handing the bottle to Tommy. “Use this. You know what you’re supposed to do, right? So do it. What do you always tell me? Show some emotion.”

Tommy smiled in pure, holy relief. “Why didn’t you tell me emotion? My God! That’s easy part! Now you see why I need you here? These other people don’t care.” He immediately started peeling off the water bottle’s sticker, because nothing scared Tommy more than hav- ing to pay someone for permission to use a logo. Tommy is probably the world’s single most copyright-obsessed human being who does not also have a law degree.

Sandy joined us on the side of the Rooftop set. He looked for a long time at Tommy’s water bottle before speaking.

“What’s this?”

“Water bottle,” Tommy said.

Sandy took in a lungful of deep, calming breath. “Yes,” he said. “I know. What are we doing with it?”

“I need to throw something, dammit. During scene.”

Sandy turned away, removed his glasses, sat down, and rubbed his eyes.

Tommy headed back to the outhouse, his water bottle in hand and his script hidden in his breast pocket. I sat down. Sandy stood by the monitor. “Action!” The door flew open and there was Tommy hold- ing his water bottle and stepping out of the outhouse and hitting his head on the doorjamb so hard that it took twenty minutes to ice the bump and conceal it with makeup. I heard one of the cameramen say, desperately, “How are we ever going to get this? It’s impossible. We’ll be here forever.”

Then, just for comic relief, Don and Brianna arrived on set to pick up their checks. Tommy, sitting in the makeup chair while Amy iced his forehead down, ignored them at first. Brianna talked to Juliette as Don ginned up the courage to approach Tommy. Their brief, chilly exchange ended with Tommy signing two $1,500 checks. Don, I could tell, was a little relieved not to be doing The Room. Really, he was surprisingly decent about the whole thing, even telling me that someday we’d be able to laugh about this. Tommy had deigned to acknowledge Don, but he wouldn’t, for whatever reason, talk to or even look at Brianna.

I gave Brianna her check. “Look at him,” she said, holding it as though about to rip it in half. Tommy was still sitting in makeup, press- ing an ice pack to his forehead. “He won’t even acknowledge me. He’s such a pussy.”

Tommy noticed me idling too long with Brianna and called me over. “Greg! I need you here!” He wanted to continue running his lines. It was hopeless. He still couldn’t remember them—and now, to make things worse, it was possible he had a concussion.

Sandy and I huddled together and came up with a handy formula for Tommy to remember. When I returned to Tommy I said this: “Okay, so here’s what you do: ‘I did not,’ mad, mad, mad, throw the water bottle, stop, notice me, look up.” Tommy asked that I repeat the formula. Several times. “Show me once more,” Tommy said. By now his bruise had been buried beneath a beige snowdrift of concealer. He was, finally, ready. He took a breath, returned to the outhouse, and did the scene. At long last we got the shot. It took three hours and thirty-two takes, but we got the shot.

If you can, I implore you to watch this scene. It’s seven seconds long. Three hours. Thirty-two takes. And it was only the second day of filming.

From THE DISASTER ARTIST by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell.

Copyright © 2013 by Greg Sestero and Thomas Carlisle Bissell. Reprinted

by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.