Jehane Noujaim was meant to be in Tahrir Square on January 25, 2011, that momentous date when millions of Egyptian citizens took to the streets to protest for change in their country. She'd been filming in the city in the months running up to it, documenting the work of three women fighting for social justice in Cairo. She'd heard the rumblings, foretelling what would become one of the largest gatherings of civil resistance. But she didn't attend.

The well-known documentarian had been invited to Davos, better known as the home of the World Economic Forum, and was wooed by the prospect of being in sessions with global leaders -- more specifically, Arab leaders who'd likely also heard those same rumblings she had. So to Switzerland she went, with one eye on the planned demonstrations at home.

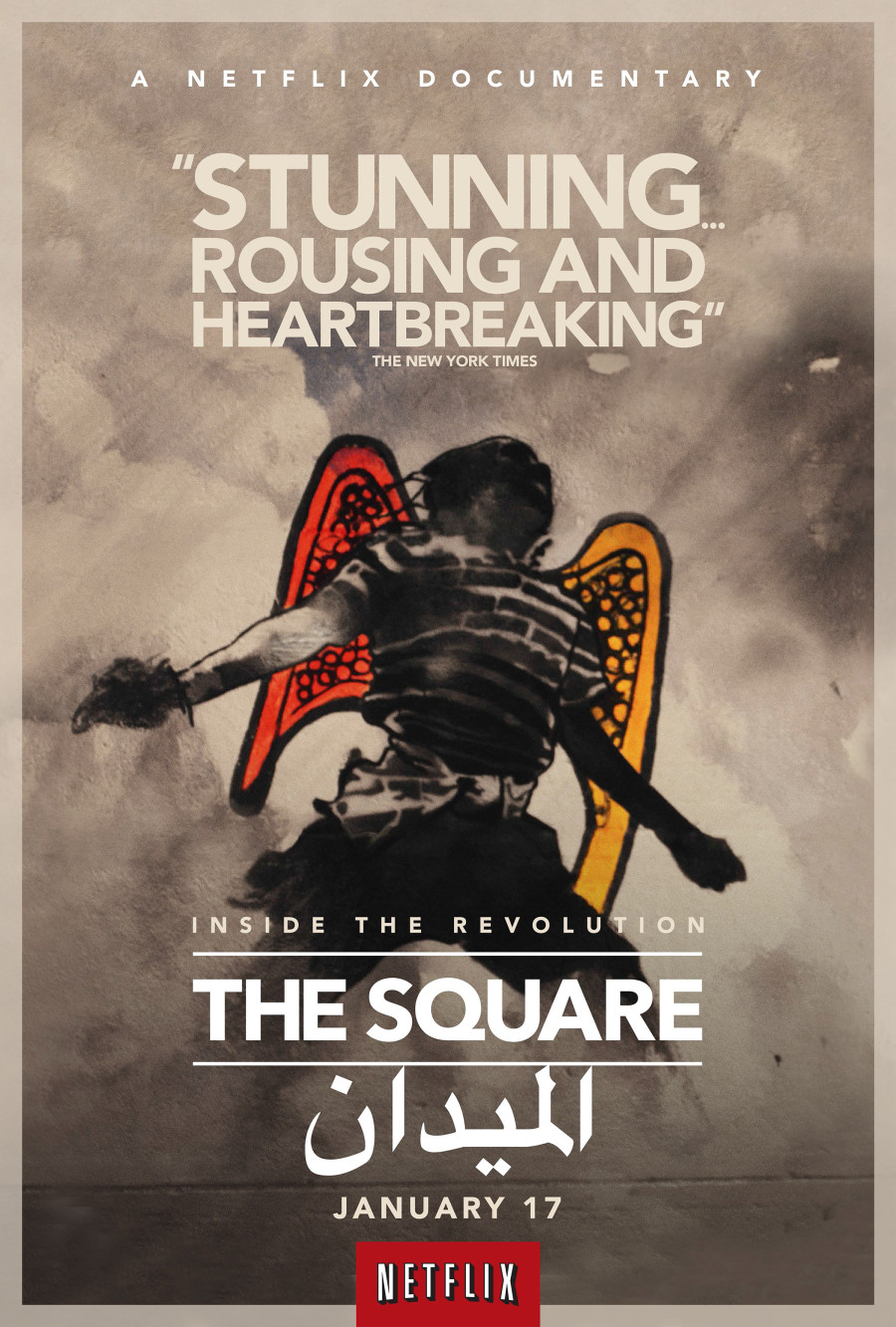

Ahmed Hassan in THE SQUARE. Photo credit: Netflix/Noujaim Films

And then the 25th happened. As predicted, throngs of Egyptians, namely young people, met in the Square, demanding not only the end of President Hosni Mubarak's regime, but also an end to corruption, economic injustice and human rights violations. "People were attacked by police like in other protests, but the difference here was that people went back in big numbers afterward," Noujaim explained. "And they kept coming. They marched toward the square, overtook it, and rejoiced with millions."

Of course, no one from the Egyptian government was in Davos and Noujaim, urged by friends on the ground at the protests, left for Cairo in a heartbeat. And so began "The Square," Noujaim's gripping portrayal of Egypt's revolutionaries, young men and women who occupied Tahrir Square from 2011 to 2013, determined to make their voices heard far and wide. Her story follows Ahmed, a street poet; Khalid, a famous actor; Magdy, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood; Ragia, a human rights lawyer; Ramy, a protest singer; and Aida, a filmmaker. From these various perspectives, Noujaim poignantly outlines the unity amongst Islamists, members of the army and Christians that marked the first months of protests, and later the schism between the Muslim Brotherhood, the military and the rest of the Square.

The work just became the first Egyptian-made film to be nominated for an Oscar, only nine days before the three-year anniversary of the protest's first breath. While it has yet to see its uncensored debut in Egypt, the documentary hits Netflix on Friday, January 17, bringing "The Square" to over 40 million global subscribers. In the run up to its release, we got the chance to speak to Noujaim and "The Square" producer Karim Amer. Here's what the duo had to say about revolution, social media and the fate of democracy in their country.

Your film begins in January 2011, just as the protests in Egypt kicked off. When did you arrive in Cairo?

Jehane Noujaim: I was in Egypt at the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011, filming “Egypt We Are Watching You,” about three women who were fighting for human rights and social justice before their time. There was talk of people going down to Tahrir Square on [January] 25th, and these women were like, “I think it’s going to big.” But I had also been invited to Davos, and I thought it could be quite interesting. So I went. After the protests in the Square broke out, I polled friends on the ground, and they said, “Get to Cairo.”

But they warned me that camera equipment was being confiscated at the airport. The government didn’t want journalists coming in and filming. So I arrived at the [Egyptian] airport just when the army had taken to streets, and -- as my friends had predicted -- all my cameras were confiscated except my small Canon DSLR. I was taken aside to be questioned, and I was just shocked to see this person was going through my things -- in plain clothes. This was all very new to me. And then they started asking me if I had ever made films in the country. The thing was, I had never put my name on the film I had done -- “Egypt We Are Watching You." I had used a pseudonym because my family still lives in Cairo, and my dad was sick, so I didn’t want problems coming into the country. Well, it turns out, the BBC had given me copies of the film -- one of which was in my car -- and was an Arabic-translated copy that, for some reason, had my real name on it. So I was taken in for questioning, seeing people outside being led into rooms and blindfolded, and at a certain point I thought, “I have to get rid of this DVD.”

Somehow I was allowed to leave the interrogation room, and I ran to my car [parked outside] and broke up the DVD and shoved it down a toilet drain. I went back into the interrogation room and three minutes later, a guy who had been cleaning toilets came in holding a piece of the DVD in the air. It sounds like something out of a movie. I had a lump in my throat and fear in my stomach. I choked on my words. I started admitting that I had made films before... the last one I made was with three incredible women. "We all know we need change," I said, "and I intend to go to the square after you let me go." Something broke and I just thought, I’m going to say exactly what I feel. After that, I went directly to the square. I saw people of all religions, joined by so many people who wanted to take things into their own hands and change things.

How did you begin the actual filming?

JN: I quickly began to look for characters -- the film is character driven -- to appeal to people. I was looking for characters that people were going to relate to. I met them in the first couple of weeks of being there. And entire crew that worked with me. We were all sleeping together on cardboard.

Khalid Abdalla (L) and Aida El Kashef (R) in THE SQUARE. Photo credit: Netflix/Noujaim Films

What was your -- and your characters' -- perception of Mubarak before the protests?

JN: I moved to Egypt as a really little kid when he came to power. For me, Mubarak was always the president. He represented a very far away figure, somebody who’s worst crime was taking away the opportunity of a whole young generation. For my family working in Egypt, conversations around the dinner table revolved around how this project or that project could happen only because so-and-so is involved, related or attached in some way to the president. It was cronyism. There was this feeling of being trapped.

Kamir Amer: Seventy percent of people in Egypt are under the age of 40. So for most, Mubarak was the only face of rule. Egypt is the land of the pharaoh, you know, it’s the the way we’ve always been governed. What happened in that Square was that the pyramid was flipped upside down. Individuals finally had power.

"Youth" became a common descriptor for the people gathering in Tahrir Square, and media outlets were keen to focus on the fact that young people were present at the demonstrations. What were the advantages and disadvantages -- for the revolutionaries -- of being referred to as youth?

JN: The advantages were that for many people -- because they knew 70% of Egypt’s population was under the age of 40 -- a youth movement was important.

KA: You know how people use the word millennial in the United States? All the marketing and television shows that center on that word. It’s one of those things. The problem is that the youth were never involved as they should have been. The presence of youth gave legitimacy to the protesting groups, but the groups never put youth in decision-making positions. For example, the youth taking part in the original 18 days with the Brotherhood -- their participation gave agency to the Brotherhood. They challenged the non-democratic, top-down perception of the Brotherhood.

But it’s always a battle of narrative. One of the overlooked parts of the situation is that the youth has a lot more in common with each other, on generational lines. Whether a young person came from the side of the Brotherhood or the military. And for young people the older generations were stuck in past.

Ahmed Hassan in THE SQUARE. Photo credit: Netflix/Noujaim Films

Social media obviously plays a part in the generational divides.

KA: Yes. The use of social media and citizen journalism is an attempt to show people that there is another narrative. History will not just be written by the victors. One person taking a photo can make an impact. When an image of a body being dragged makes its way to national media outlets, and then the Egyptian media is forced to address it, it makes a difference. Not only will people be killed but that’s the way the fight is taking place.

We are also dealing with an archaic generation of military and police able to act with impunity. There’s a scene in the outtakes of the film, when Ahmed had filmed an officer shooting bullets out of a gun at a protester. He filmed it with a cell phone camera and brought it into a news station, which then brought in a general to be interviewed about it. They played the footage four times before the general admited that bullets were coming out of the gun. “[The armed officer] must have brought his own weapon,” the general said. “We did not provide weapons like that.”

But slowly, because of the use of social media, television stations were showing this and questioning. Demanding that the government be accountable.

Surveillance became an obsession for both the military and the revolutionaries, as the latter began to use footage of protests and clashes as “evidence” against the former. You’re documentarians who were simultaneously collecting footage yourself, so what was your sense of the need or desire for surveillance?

JN: Yeah, who is watching who, right? When I made the film “Egypt We Are Watching You,” as I was making it, I noticed that every time I would leave from interviews with the women, they would get a call from the secret police. “Hey, I thought you said the filmmakers were gone,” they would say. Somehow I was being watched during filming. I’d be standing in a square, and I’d look to my left or my right, and I’d find someone with a cellphone camera. They would look a little suspicious -- wearing a suit and filming you. And you just know you’re going in some kind of hard drive.

A few characters from the film, they found files of themselves in a security building. Some of the protesters had stormed the state security building because they knew a lot of the documents were going to be burned, and they wanted to save documents because they felt there would evidence there that could be used later. You know, it was all about protecting the narrative. They went in, stormed the building, and they found files on themselves. Not just photographs of many of the activists in the square, but surveillance from years earlier, just having dinner. It was fascinating.

KA: In Egypt you’re still watched physically.

Also, in one the deleted scenes of the documentary, we were interviewing one of the military’s generals, and we were talking about the security state and how ridiculous it was that surveillance was still happening. “You think Egypt is the only country doing this?” he asked. “The U.S., the land of freedom and democracy, has files on everybody. At least we don’t claim to have freedom and democracy.”

Khalid Abdalla (L) and Ahmed Hassan (R) in THE SQUARE. Photo credit: Netflix/Noujaim Films

Your film shows the unity that prevailed at the beginning of the protests and the divide that occurred after rumors surfaced that the Muslim Brotherhood made concessions to the military. What is your sense of the current relationship between the Muslim Brotherhood and the other revolutionaries?

KA: The revolutionaries really feel betrayed by the Brotherhood. We stood side by side in the square, and understood that this was a collective mission. And then we have this election -- an election between the one who killed us and the one who betrayed us. When Mohamed Morsi did come to power, there was this feeling of betrayal. The first freely elected president used the tools of democracy and religion to create another dictatorship.

There was outrage. It was almost worse than what was before, because this person was elected. After going through this taste of democracy, it was such a slap in the face. You could hear the doubters, saying Egyptians were not ready for democracy.

Of course the revolutionaries do not agree with what’s happened in terms of the force used against Brotherhood protesters or assaults of the Brotherhood in the past or making them illegal. But their actions really cost the country a lot. It made a lot of people exhausted with the democratic process already.

Was this the first time you were this close to demonstrations of this scale, with the violence that did end up occurring?

JN: Yes. Yes. You know, if you asked me a few years ago if I would have put myself in these situations, I would’ve said you’re crazy. But if you think about it, if all the people you loved were in one square, being arrested and shot at for no reason, there’s an incredible feeling that comes with that. A lack of fear that comes, and a desire to fight for what you believe. I learned a dedication to principles from the people I followed. I was forever changed by this experience, by being in the Square. It changed my understanding of possibility.

THE SQUARE director Jehane Noujaim. Photo credit: Ahmed Hassan

Have you witnessed any backlash against the film and the way that it portrays individuals?

KA: A lot of people aren’t used to documentary films that are character-driven. They assume a documentary will give a more historical, narrated account of all the events that occurred in a period of history. That’s very different than what we set out to do. No one owns this narrative, people will be making movies and writing about this for years. We wanted to make an emotional, character-driven film, a slice of what it was like to be those people. That’s what we set out to do. This film is really about capturing the fight for human rights and democracy in the 21st century and the tools used to do it. Whether it’s Kiev or Athens, we’re all part of a global movement to hold people accountable.

JN: This film is about exposing human rights abuses and giving voice to this narrative of kids fighting for social change and justice and freedom in Egypt. It’s so crucial for us to have the opportunity to get this film out across the states and Egypt. It creates a type of witnessing, awareness of the people who are still fighting on the ground. It creates protection. The international community is watching, because it’s all interconnected. Human rights abuses in one area will mean human rights abuses in other areas. It’s a human struggle no matter what.

KA: Right now, the army is trying to white-wash history. The reigning government could stop our film, but what they don’t understand is that it makes people want to see it even more. There have been underground screenings, and watching the film has become a subversive act.