Hobby Lobby's overt Christianity shocked Charity Carney when she started working at a Texas outpost of the crafts chain a few years ago. Most staff meetings began with a prayer, Carney learned. You could always find a Bible in the break room, she said.

“It was just assumed that you would be a believer if you worked there,” said Carney who left the company after a few months and is now a historian, studying the rise of megachurches at Western Governors University. “I don’t think anybody would be persecuted for not believing, but there was an assumption in place.” She said she eventually got used to it.

Hobby Lobby's religious bent was thrown into the spotlight this week when the Oklahoma City-based crafts chain argued its case against Obamacare's so-called contraception mandate before the Supreme Court. The company, which employs 16,000 workers in its more than 550 stores, maintains that the law's requirement that health insurance cover IUDs and morning-after pills violates its religious rights.

Hobby Lobby's founders leave the Supreme Court after oral arguments Tuesday. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Though the idea of a company with an overt religious commitment -- and the belief that contraception is a religious issue -- may seem surprising in 2014, there's a long-standing American tradition of mixing religion and work going back more than 100 years.

“Religion has been a part of corporate America for quite some time,” said Darren Grem, a historian at the University of Mississippi who studies the intersection of business, religion and politics. The Hobby Lobby case “is a new conflict over a relatively old issue.”

In the early 20th century, Southern textile mills built churches and hired pastors in company-built towns. Employees heard sermons on the value of working, abstaining from alcohol, and marital fidelity. Companies believed these so-called Christian values would help maintain a stable workforce in several ways.

“As you might expect, the company preacher preached the line that encouraged employees not to join unions,” said Jarod Roll, also a history professor at the University of Mississippi and the author of Spirit of Rebellion: Labor and Religion in the New Cotton South.

A late 19th century mill located in Columbus, Ga.

As the Evangelical right wing movement started to take shape in the latter half of the century, religious entrepreneurship became more common. “There’s a long history of Evangelicals using workplaces as a place where they preach,” said Grem.

Indeed, when Southern Baptist Cecil B. Day originally founded Days Inn in the 1970s, he banned the sale of alcohol in the hotel’s rooms and put a Bible in each one. He also encouraged in-office voluntary prayer meetings.

Even Walmart’s workplace culture incorporates a certain sense of “Christian duty serviceship," said Jarod Roll, a history professor at the University of Mississippi. The company “has an economic base in communities that are religious, and the workforce is deeply religious,” he said.

An open Bible in a Days Inn in Mississippi. Flickr/damian entwistle

There were times in history that a religious dynamic worked against management. During fights for better wages and working conditions throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, employees often wielded Bible phrases and religious notions of morality, Roll said.

The fact that Hobby Lobby and other religious companies likely employ some workers who don’t believe is part of the reason asserting religion at work has suddenly become so controversial, Roll said. That's a marked change from the past: The textile mills of the early 20th century were staffed by an almost 100 percent Protestant workforce; big factories in Detroit or Chicago during the same period were also largely staffed by Catholics, he said.

Today, it's much less likely that a secular business would have employees of all the same religion. In addition, an increased government focus on preventing discrimination as a result of the civil rights movement has produced a body of legal rulings that protect employees' religious rights at work.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits secular businesses from discriminating on the basis of religion. Before that, “if you were a Protestant and you didn’t want to hire or promote a Catholic there was little legal recourse for that Catholic employee,” said Grem.

Those rules are largely enforced through employee complaints or lawsuits.

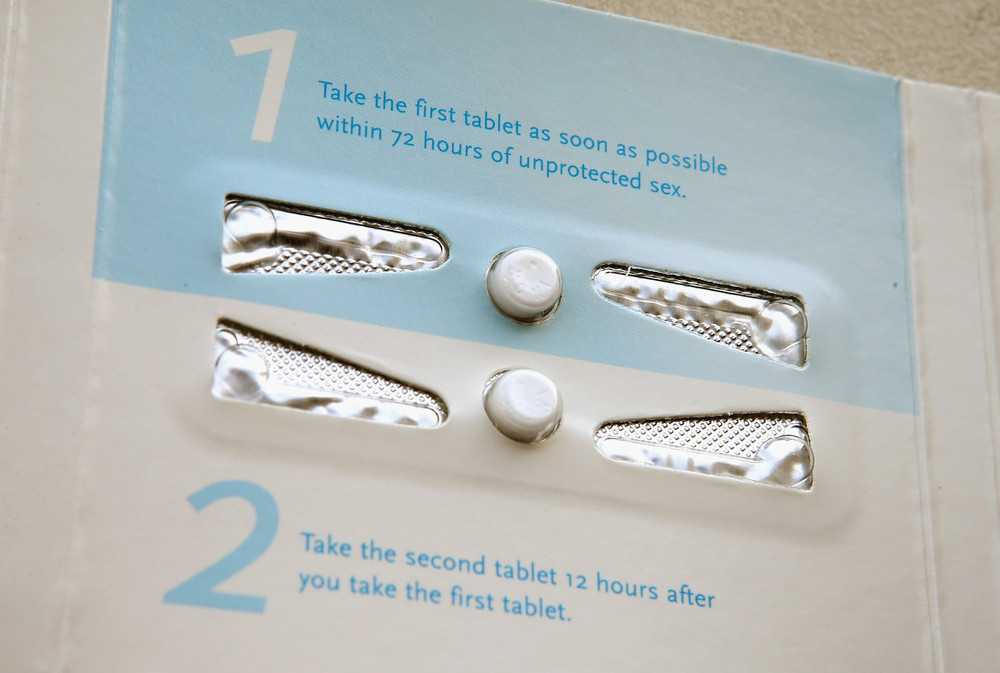

At issue in the Hobby Lobby case, however, is whether complying with a new law, Obamacare, gets in the way of the company's owners expressing their religious beliefs. The high court will decide whether the Green family, the Southern Baptist owners of Hobby Lobby, can refuse on religious grounds to cover certain contraceptive devices for their employees as mandated by the Affordable Care Act. The company is targeting intrauterine devices (IUDs) and the Plan B pill.

Plan B pills. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Carney said that in her experience at Hobby Lobby, workers who didn't believe in the company's Christian values had reason to just take it in stride. Part of Hobby Lobby’s Christian corporate culture also means that the company pays its workers more money than similar retail jobs.

The company starts workers at nearly double the minimum wage, according to the Associated Press. Hobby Lobby also offers employees health, dental and retirement benefits. The company did not respond to a request for comment.

“They pay good wages,” said Carney, who was with Hobby Lobby only for a few months before she quit the store because she felt her manager forced her to work too many hours one day. Carney said she was only able to leave Hobby Lobby because she had already scored her current gig in academia.

“Everybody was glad to have the job, we wanted to keep the job so we didn’t rock the boat.”