Disturbing details about the botched execution of Oklahoma inmate Clayton Lockett have sparked a new debate on the death penalty.

Lockett died of a massive heart attack on April 29, after prison officials administered drugs in a new lethal injection combination that left him writhing and clenching his teeth on the gurney, though it's unclear if the drugs were to blame. Lockett and another death row inmate, Charles Warner, previously had sued the state for refusing to disclose details about the execution drugs, including where they were obtained.

But the uncertainty about the new drug cocktail isn't the only reason people should be skeptical of the death penalty ...

The death penalty is likely taking the lives of innocent people.

According to a new statistical study appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, almost 4 percent of U.S. capital punishment sentences are wrongful convictions, meaning about 1 in 25 people who are sentenced to death are likely innocent. This could mean that approximately 120 of the roughly 3,000 inmates currently on death row in America might not be guilty, and at least several of the 1,320 defendants executed since 1977 were innocent.

Executions can take longer than they should.

Prison officials told The Associated Press that, of the last 19 executions in Oklahoma, the average length was 6 to 12 minutes. Lockett was pronounced dead 45 minutes after his execution began due to complications with the lethal injection procedure.

But Lockett's not the only one to suffer on the gurney: On Jan. 16, Ohio executed convicted rapist and murderer Dennis McGuire by lethal injection with an untested combination of drugs including the sedative midazolam and the painkiller hydromorphone. It took him 25 minutes to die.

In 2006, it took Joseph Lewis Clark, who was executed by lethal injection, 86 minutes to die.

Executions are often botched.

Amherst law professor Austin Sarat examined every execution from 1890 to 2010 and found that 3 percent of all executions during those years did not go according to protocol. Though Sarat says these botched executions included decapitations at hangings and defendants catching fire in electric chairs, he also notes the percentage of executions not done properly hasn't gone down with the adoption of lethal injection.

"Botched executions have not disappeared since America has adopted the current state-of-the art method of lethal injection," Sarat wrote in a Boston Globe op-ed. "In fact, executions by lethal injection are botched at a higher rate than any of the other methods employed since the late 19th century, 7 percent."

An attempted execution in 2009 was so botched that inmate Romell Broom actually lived. Broom's execution was stopped after an execution team tried for two hours to find a suitable vein, sticking him with needles at least 18 times with pain so excruciating he cried and screamed.

The people being executed often feel discomfort or pain.

Michael Lee Wilson, who was executed by lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in January, told prison officials he could feel the combination of execution drugs just before his death.

"I feel my whole body burning," Wilson said before succumbing to the drugs.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice maintains a website devoted to executed offenders, which includes each inmate's last statement. Many of the statements contain phrases like "it's burning"; "I feel it"; "I'm feeling it"; "I can feel it, taste it"; and "this stuff stings."

"My left arm is killing me. It hurts bad," said Jonathan Green, executed in October 2012.

Sarat noted that pain may be inevitable in executions.

"A close look at executions in America suggests that despite our best efforts, pain and potential for error are inseparable from the process through which the state extinguishes life -- and that the conversation about capital punishment needs to take that fact into consideration," Sarat wrote.

Death penalty trials are expensive.

Death penalty trials can cost millions more than non-death-penalty trials -- a cost that's placed on taxpayers. The Economist reports:

An execution itself is not expensive, but the years of appeals that precede it are. Defendants facing death tend to have more, better and costlier lawyers. Death-row inmates are more expensive to incarcerate, too: they usually have their own cells, with meals brought to them and multiple guards present for every visit. “It’s because of this myth that these people will be executed in a couple of months,” explains Richard Dieter of the Death Penalty Information Centre.

The price of execution drugs became 15 times higher from 2011 to 2012, costing nearly $1,300.

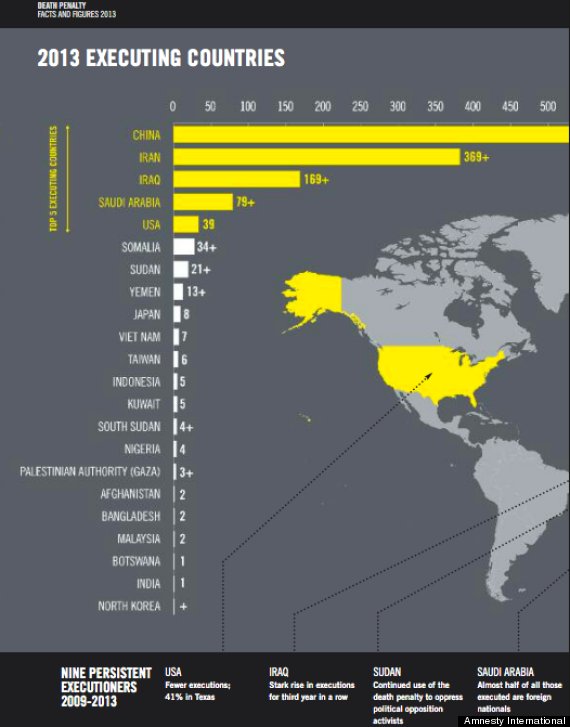

Very few countries perform executions, and we're in some questionable company with the ones that do.

The United States was 1 of 22 countries to report executions in 2013, and it is the only country in the Americas to have carried out executions that year, according to Amnesty International. Japan and the U.S. were the only countries in the G-8 to have carried out executions that year.

We're considering lowering our standards for how to execute people, rather than re-considering the idea itself.

A short supply of lethal injection drugs have led states to consider other methods of execution, including the new drug combination that left Lockett writhing on the gurney in the execution chamber.

Aside from sedatives and heart-stopping drugs, some lawmakers are considering execution methods of the past, including firing squads, electrocutions and gas chambers. Missouri state Rep. Rick Brattin (R), who in January proposed firing squads as an option for executions in his state, said his suggestion wasn't an attempt to "time-warp."

"It's just that I foresee a problem, and I'm trying to come up with a solution that will be the most humane yet most economical for our state," Brattin said, noting he thinks it's unfair for relatives of murder victims to wait years, even decades, to see justice served.

Nick Wing contributed to this report.

Before You Go