For decades, the U.S. government had a simple message on diet: To avoid chronic illnesses like diabetes, obesity and heart disease, Americans should cut back on saturated fat, cholesterol, sugar and sodium. Yet today, we're sicker than ever.

More than 29 million adults in the U.S. -- about 9 percent of the population -- currently have diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The obesity rate has more than doubled since 1980 and now hovers between 31 percent and 35 percent. About a half-million Americans die of heart disease every year, accounting for one in every four deaths.

Clearly, we need to change the way we think about food.

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services took a major step toward addressing the public health crisis by dramatically overhauling dietary guidelines. They replaced the familiar food pyramid that had informed Americans' eating habits for almost two decades with a new "food plate" that, for the first time, encouraged people to make fruits and vegetables half of their diet, while emphasizing smaller portions overall.

"This is a quick, simple reminder for all of us to be more mindful of the foods that we’re eating," first lady Michelle Obama said when she officially unveiled the plate in 2011.

But many experts say these recommendations didn't go far enough to address the major health issues facing Americans. Now, the government's Dietary Guidelines for Americans, or DGAs, are being scrutinized once again, as part of a review that takes place every five years. For the 2015 guidelines, scientists and nutritionists are calling on the USDA and HHS to go further -- to be unequivocal in condemning highly processed junk food, and more specific about which foods to eat or avoid.

"I’d like to see the guidelines move away from nutrient targets and … toward true, food-based evidence," said Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, dean of Tufts University's Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy.

In other words: Eat this, not that.

The first dietary guidelines in 1980 were designed specifically to combat heart disease, at the time public health enemy number one. Landmark epidemiological studies, beginning as far back as the 1940s and '50s, linked heart disease to sodium, cholesterol, saturated fats and trans fats. The solution appeared clear: Cut down on the butter, whole milk, hamburgers and steaks.

As consumers zeroed in on low-fat foods, however, they didn't necessarily adopt healthy diets overall. "It's not as if we're suddenly eating a lot of lentils and kale," said Dr. David Katz, a clinical instructor at the Yale School of Medicine and the founding director of Yale's Prevention Research Center. "We replaced the fat with low-fat junk food."

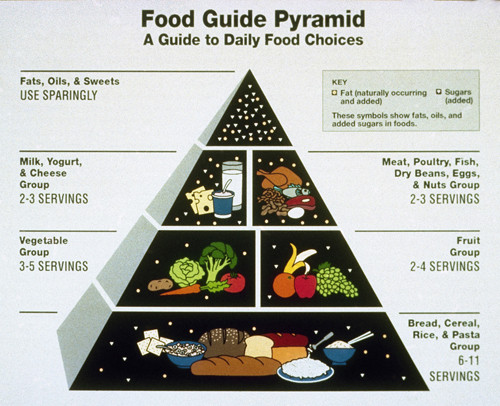

The government tacitly endorsed such products when it unveiled the food pyramid in 1992. Foods like bread, cereal, rice and pasta formed the base of the pyramid, suggesting that carbs should make up the majority of one's diet.

Companies rushed to create products that were low in fat, but high in sugars, starches and carbs. The year the food pyramid debuted, Nabisco introduced its line of low-fat and nonfat SnackWell's cookies, which proved so popular that grocery stores could barely keep them in stock. Similar products soon followed.

“It’s true that the focus on reducing fat in the DGAs implicitly led to higher carbs,” said Dr. Walter Willett, chair of the department of nutrition at Harvard’s School of Public Health. “And that became problematic, because the vast majority of carbs in the U.S. are refined and bad for you."

Studies have linked refined carbohydrates to obesity and diabetes, and since the first dietary guidelines were introduced, rates of those illnesses have skyrocketed. Meanwhile, heart disease -- the original impetus for the guidelines -- has remained the number one killer in the U.S.

Of course, the guidelines alone aren't responsible for America's current health problems. The food industry's unbridled promotion of junk food and sugary sodas has also played a major role. Socioeconomic factors make it difficult for many people to access healthy food. And people often simply ignore the advice on healthy eating. Still, scientists say it's no coincidence that diabetes and obesity rates shot up during an era in which we focused so intensely on removing fat from our diets.

The 2010 dietary guidelines represented the government's first major attempt to tackle these issues. Most significantly, the USDA and HHS attempted to correct Americans' overindulgence in carbs by emphasizing the importance of fruits and vegetables.

While the food pyramid had called on Americans to eat six to 11 servings of carbohydrates a day, the new food plate provides a simpler measure: When you fill your plate, grains and starch should occupy just one-quarter of it. Fruits and vegetables should take up half the plate, with protein making up the rest.

"People were eating much more than recommended, because we tend to underestimate portions," Stephanie Dunbar, director of clinical affairs at the American Diabetes Association, said of the old guidelines. "We underestimate our portion sizes and didn't really understand what the six-11 meant." The plate, she said, makes it much easier to eat sensibly.

"They took huge steps forward in 2010 from 2005," said Dr. Susan Levin, a dietician and the director of nutrition education at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, which advocates a vegan diet. "They acknowledge in [the guidelines] that plant-based diets are the healthiest way to eat, and if we could get people eating more like that, then we'd have less prevalence of these chronic diseases."

The new message may be doing some good. A recent Gallup survey found an that an increasing number of Americans said they were consuming more fruits and veggies than in previous years -- and a great deal more said they were avoiding soda and added sugars. Of course, it's not clear whether Americans really have changed their diets for the better. But at the very least, they appear to be more aware of what healthy eating habits look like.

Still, experts caution that the government still has room to make significant strides.

The 2010 guidelines, for example, advise that between 45 percent and 65 percent of calories should come from carbohydrates, a recommendation that some scientists say is overly vague and confusing. As if serving and portion sizes weren't confusing enough, Americans are now left to try to calculate how many calories are in a bowl of cereal or a slice of toast.

New research also suggests that our demonization of fat may need to be reconsidered. The 2010 dietary guidelines committee found strong evidence linking saturated fat with high cholesterol and increased risk of heart disease and Type 2 diabetes, the form of the disease associated with obesity and inactivity. But recent studies suggest that, in our eagerness to avoid the negative effects of fat, we may be missing out on health benefits.

For example, the dietary guidelines recommend fat-free milk to satisfy calcium requirements, while staying below limits on saturated fat. But some studies show that whole milk may play a role in reducing diabetes risk.

One of the subcommittees working on the 2015 guidelines plans to investigate the issue of saturated fat before September, when the group will present its findings. "There is an intention to look at the more current evidence," said Trish Britten, a nutritionist with the USDA's Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion who helped manage the 2010 guidelines and is involved in the 2015 process as well.

Other researchers argue that the guidelines' emphasis on specific nutrients misses the larger issue of how food is processed. “It’s much more important for the meat you eat to be unprocessed than what its fat content is,” said Mozaffarian. “That’s pretty meaningless, actually. What’s much more important [is] how much it's been processed, sodium, how you cook it. I’d really like the guidelines to move away from [their] focus on single nutrients and fat.”

Britten said the 2010 guidelines began a food-focused approach that will continue in the future.

Of course, recommending that Americans eat wholesome, organic, well-balanced meals might seem to ignore people at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum, who don't have a neighborhood Whole Foods, or the time or money to prepare home-cooked meals. But dietary guidelines that promote healthier foods will improve the diets of the poor as well.

"The DGAs are important because they inform a host of institutional and governmental nutrition programs, including school lunches, SNAP guidelines and meals in the military," said Willett.

Still, coming up with national recommendations for something as individualized as health is a challenge. Browse the latest research on nutrition and health and you’ll find studies and interventions for every ethnic group, age range and medical need. Yet aside from recommendations on sodium intake that are broken down by age, race and medical history, the government's dietary guidelines offer only one-size-fits-all suggestions.

Making specific recommendations about which foods are healthy and unhealthy also may pit the government against the powerful food industry.

Food-based guidelines are "too politically fraught," said Dr. Marion Nestle, professor of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University and author of several books on food industry politics.

"No industry wants the government telling people to eat less of its products," Nestle told HuffPost. "That’s why the 'eat more' recommendations refer to foods, but the 'eat less' refer to nutrients."

"While the new guidelines talk freely about foods to encourage, foods to limit are buried deep in the 95-page report," Caroline Scott-Thomas, a journalist covering the food industry, wrote after the 2010 guidelines were unveiled. "Instead, they focus on SoFAS -- solid fats and added sugars -- an unhelpful euphemism for many of the unhealthy foods in our diets."

The USDA disputed the notion that its guidelines are subject to outside pressure.

"There was no influence in the course of time we were involved in 20 months," said Dr. Linda Van Horn, a professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine who served on the 2010 DGA committee. "Any interest whatsoever that came forward from industry was completely redirected, and none of the members of the committee had anything to do with the food industry."

Yet the food industry has shown it is more than willing to fight regulations it views as threatening. In 2011, it launched an intense campaign to defeat voluntary nutrition guidelines for foods marketed to children, an effort that is still ongoing. And in 2009, the American Beverage Association, Coca-Cola Co., and PepsiCo spent a combined $37 million on lobbying to help kill a proposed federal excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages.

Some health advocates said they worry that the new government dietary guidelines -- however improved they may be -- will do little to benefit Americans' overall health, given the outsized influence of the food industry.

"I've never seen a government tell people to eat more processed food. The dietary guidelines never told people to drink more soda and eat more cookies," said Dunbar. "There are many determinants of obesity, and it's not just a matter of carbohydrates and fat. You have sociological issues, the food that is available in communities, and billions of dollars promoting sugary drinks.

"It's very hard for public health advocates to counter the information produced from that industry," she said.

Still, experts said they hope the 2015 guidelines will help drive home the message about healthy eating habits.

“If they change anything, I hope it’s a more explicit emphasis on 'here are the dietary patterns that make people healthy,' 'here are the foods that populate those dietary patterns,'" said Katz. “That would really be the answer -- because if you eat wholesome foods in sensible combinations, you win.”

CLARIFICATION: Trish Britten's statement about the USDA's food-focused approach in its guidelines was previously misattributed to a USDA spokeswoman.