Half of the 120,000 prisoners were children. It was the start of the War Years, the turning from 1941 to 1942. Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered 90 percent of America's ethnic Japanese from their homes in retaliation. For four years, they lived in bleak camps edged in barbed wire, deep inside deserts and swamps. Internees were allowed only what they could carry, including bedding and eating utensils. Upon arrival there were no chairs to sit on, no tables to eat at, no tools to build with or scissors with which to cut.

What do you tell someone who has lost everything? In Japan, there is actually a word for the occasion: "gaman," a quality both hard and soft. To practice gaman is to endure that which seems unendurable, with patience and grace.

To practice gaman is to make something from nothing. Interned men, for instance, used the boiler furnace to melt scrap metals -- old saws, car springs, butter knives. With this liquid, they fashioned their own tools. In a camp in Rowher, Arkansas, Akira Oye hammered out a pair of scissors so lovely they could be the mascot for scissors everywhere.

Collection of Ron and Michiko Oye and Family. Courtesy Bellevue Arts Museum.

Oye's scissors, Homei Iseyama's teapot, carved out of slate stone Iseyama, a gardener, found near his camp in Topaz, Utah: these and other ingenious relics make up an exhibit exploring a rarely seen side of the awful internment years. Titled The Art Of Gaman, the traveling show is the brainchild of Delphine Hirasuna, a San Francisco-based curator whose parents and siblings were imprisoned in Arkansas. Going through her mother's things one day, Hirasuna found a wooden bird. The trinket, her mother explained matter-of-factly, was personal -- made by her hands. What else was out there, Hirasuna wondered? How many gems crafted in the gloom of the barracks were secreted away in attics and forgotten?

Hirasuna explains in a video for the Smithsonian Institute how her decade-long hunt to answer that question led her to the title of the resulting exhibit. As she knocked on doors, picking up objects from former internees and their family members:

"Virtually every person I borrowed an object from said that this was their way to gaman. This was their way to grin and bear it."

Another piece by Oye, this one a cow made of pine and shellac. Collection of Ron and Michiko Oye and Family. Courtesy Bellevue Arts Museum.

The exhibit originated at the Smithsonian in 2010; it returns now to the U.S. after a stop in Japan. In a breathtaking essay inspired by the homecoming, Jen Graves at the Stranger notes the special significance of the show's current location. The Bellevue Arts Museum in Washington is "a stone's throw" from "vast tracts of strawberry farms [that] were leased and owned by Japanese Americans forced off to camps," according to Graves. The few who made it back were shunned "by the businessmen who snapped up the land where skyscrapers, the mall, and the museum itself stand today," she writes.

Along with the tools and everyday objects on display are woodcarvings, paintings, furniture and toys. While some were made by artists renowned today, like Ruth Asawa and Henry Sugimoto, most of the exhibit's items came from people simply making do, according to Hirasuna.

These shopkeepers, farmers and fisherman "did not have trained artistic skills, but they made amazing things from a variety of material," she says in the Smithsonian video. Oye, for instance, who made both the scissors and the pine cow above, was a farmer in Lodi, California before and after the war. While in Arkansas, he carved many familiar animal and birds. He never carved again after the camps closed.

Scroll down for more images from The Art Of Gaman, from a pair of elegant wooden cranes to Iseyama's slate teapot. All photos and captions provided by the Bellevue Arts Museum.

Teapot, by Homei Iseyama. A self-taught artist, Iseyama attended Waseda University in Tokyo before coming to America in 1914 with the hope of attending art school. He was forced instead to seek full-time employment as a gardener to survive. At Topaz, in addition to making slate carvings, he demonstrated his artistic range through watercolor paintings and tanka poems. A landscape gardener in Oakland, California, before and after the war, Iseyama was also a widely respected bonsai master. Collections of Carolyn Holden, Aiko Iseyama and Family, and Martha Perdue and Family.

Assigned to tend the boiler while interned at Minidoka, Idaho, Kametaro Matsumoto amused himself by whittling and carving things for his children. Using scrap wood, he carved this puzzle and hand-painted the blocks. The object of the game was to move the blocks without lifting them so that the fair maiden could escape the protective attention of her parents and servants and let herself be surrounded by the four eager suitors. Collection of Alice Ando and Jean Matsumoto.

Wood carving of little birds was a prevalent art form in all of the camps. A set of Audubon bird identification cards and an old National Geographic issue that featured birds were sources of research and inspiration for many carvers. To create them, artists sketched an outline on flat wood, carved and sanded it into a three-dimensional form, then painted it with realistic colors. The biggest challenge was the bird’s legs and feet, which had to look spindly, yet be sturdy enough to hang onto a “limb.” Many artists solved the problem by snipping the surplus off wire-mesh screens that had been slapped over barrack windows. The wire proved to be just the right thickness and strength to resemble bird legs. The final touch was to glue a safety pin onto the back of the carving so it could be worn as a brooch. These animal pins were crafted out of scrap wood by Himeko Fukuhara, Kazuko Matsumoto, Sadao Oka, and other unidentified artists interned at Amache, Colorado; Gila River, Arizona, and Poston, Arizona. Collection of Jewel Nishi Okawachi, Japanese American Citizens League, San Francisco, Collection of Sadao Oka Family.

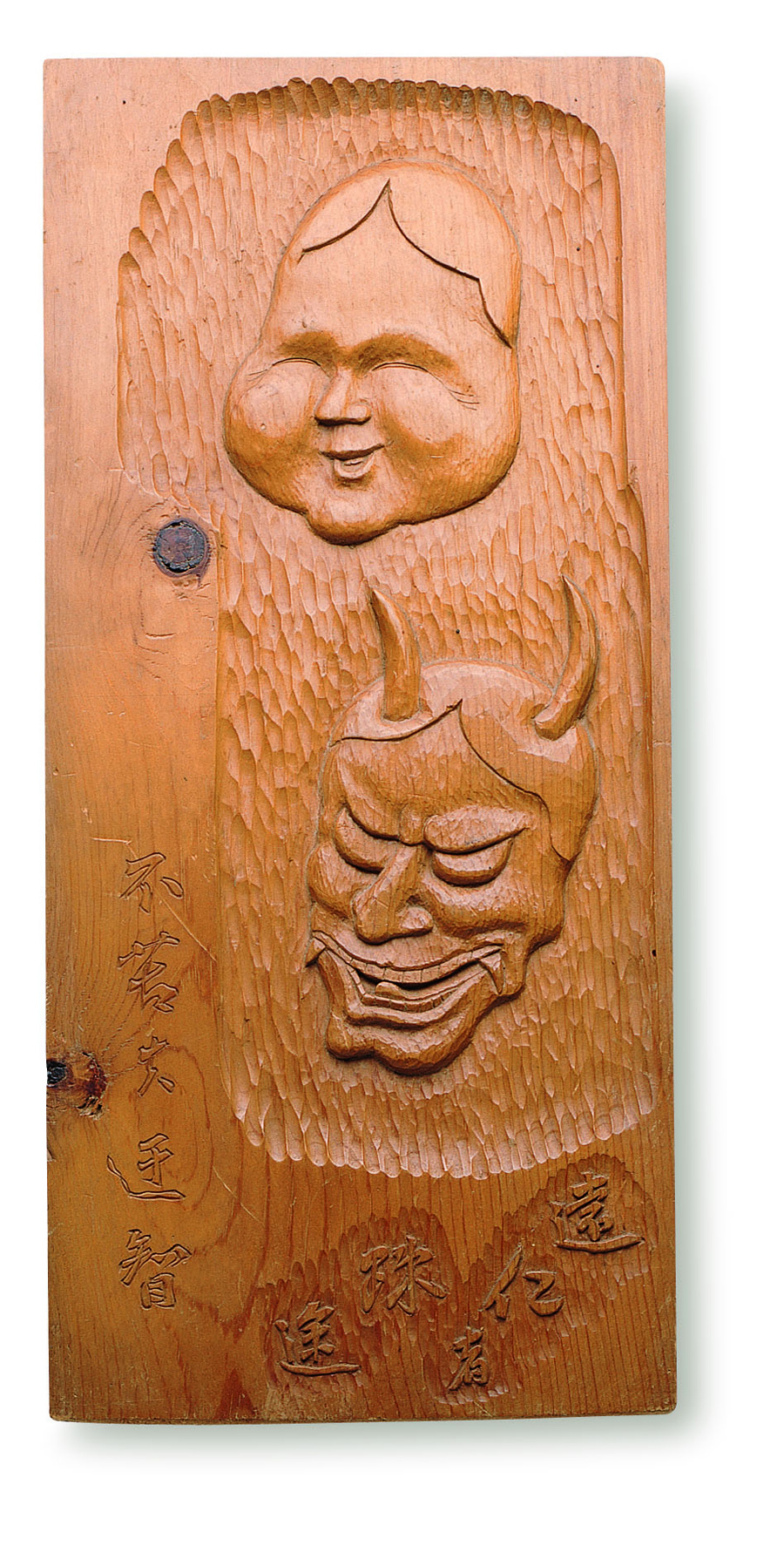

While interned at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, Kameichi Yamaichi made his own tools to carve this classical Noh mask panel. By heating worn triangular files -- which were sought after material for their durability -- in the coal-burning potbellied stove in his barrack quarters, he was able to pound out the metal to form a chisel. He then used a stone to sharpen it. Collection of the Japanese American Museum of San Jose.

Before the war, Kinoe Adachi and her husband owned a Chinese restaurant in Oakland, which they lost during the internment. A creative person, she had always sewn clothes and made quilts. This exquisite samurai is one of several pieces that she made at Topaz, Utah, out of shells. When she left camp, she took her jars of sorted shells with her. She and her husband bought a home in Berkeley upon their return, where she took care of him after he suffered a stroke. Collection of Dennis Katayama and Family.

Jitsuro Hiramoto, a farmer in Lodi, California, was 55 years old when he was arrested by the FBI the day after Pearl Harbor and sent to the Santa Fe Detention Center in New Mexico. He was later transferred to Rohwer, Arkansas, to join his family. He made this pair of cranes while in Santa Fe, out of mesquite and scrap lumber. During the war, Hiramoto's son served overseas in the U.S. Army. Collection of Edward Hiramoto and Family.

Related

Before You Go