Jeremy Shatan met his future wife, Karen Capucilli, when he was just 16 years old. She was his sister's friend and had come over for a visit. It was love at first sight.

"You wouldn't believe these things can happen," Shatan told The Huffington Post. "But they can."

The pair went to the same college, graduating in the mid-1980s within a year of each other. They were married soon after. But they waited nearly a decade before trying for a baby, instead working hard to establish themselves as freelance editorial and commercial photographers in New York City. Eventually, they felt ready. Capucilli got pregnant in 1996, and in 1997, their son Jacob was born.

The pregnancy and birth were normal and healthy -- "just a beautiful experience," said Shatan. He and Capucilli were devoted, if slightly bumbling, first-time parents.

"Jacob was the most perfect first child you can imagine," Shatan recalled. "We'd be fumbling around trying to figure everything out -- it would take us an hour to just run a bath -- and he would just look up at us peacefully. He was delightful."

Then, on an otherwise typical March morning in 1998, Jacob -- who was 14 months old at the time -- woke up and seemed somehow off. He was fussy and clingy. He threw up. Capucilli made an appointment with their pediatrician and the couple went on with their lives, but days later Jacob appeared lethargic, so she rushed him to the emergency room. After hours of waiting and testing, it became clear that the problem was life-threatening.

"Who knew that children get brain tumors?" said Shatan. By 10 p.m. that night, however, the shellshocked parents listened as Jacob's doctors said that very thing. "They thought it had probably been growing for three months," Shatan said.

"The devastation," he said, "you can't even imagine. Talk about innocence lost."

Within 24 hours of being diagnosed, Jacob underwent surgery to remove what is known as a primitive neuroectodermal tumor. The procedure was long and difficult -- one of the bloodiest the surgeon had ever done, Shatan said -- but ultimately successful.

The young family then settled into something resembling a routine, albeit one dominated by doctors, interventions and nervous waiting. Jacob endured six cycles of chemotherapy, during which he was regularly gripped by sudden fevers. Shatan and Capucilli grew accustomed to rushing him to the hospital to have the fever knocked out. He had a stem cell transplant, which wiped out his immune system and rebuilt it using his own stem cells.

In between, the family found time to come together over meals in their apartment in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan, and Capucilli and Shatan continued to work as photographers. They tried for another baby, and Capucilli soon got pregnant with their daughter, Hannah.

"We felt like we rose to the occasion," Shatan said. "We had normalized this horrible situation."

Their son also thrived as best as he could. Many young children emerge from such grueling cancer treatments in a weakened state, but Jacob seemed strong, almost more himself than ever before. Capucilli and Shatan felt hopeful, even confident, that their son would survive.

But in March 1999, almost a year after his original diagnosis, Jacob's cancer came back.

"One of the worst parts was that the doctors were surprised -- they were shocked," Shatan said. "They really thought they had dealt this thing a death blow."

Instead, the doctors told Jacob's parents he had only a few months to live.

Capucilli and Shatan decided, at that moment, to treat their son like he was a little guest, visiting New York City -- where he had in fact lived his whole life -- for just a short while. They did all of the things tourists do, in an effort to make the most of their final months together. They went to museums and cheered at a Knicks game. Shatan, a music enthusiast, took his son to one of the sprawling Virgin Megastores then found in the city, where Jacob picked out a few albums he liked, and his father picked out a few artists he really wanted his son to hear.

"The ones that really took off for him were Lucinda Williams and Massive Attack -- he went to some other zone when he was listening to those," said Shatan. "But his favorite was Leon Parker, the percussionist."

On June 8, 1999, after a stretch of several wonderful, if bittersweet, months for his parents, Jacob died. He was 2 and a half years old.

"You go through that experience, and you feel just about 1,000 years old," said Shatan, who is now 49. "And then nothing is the same."

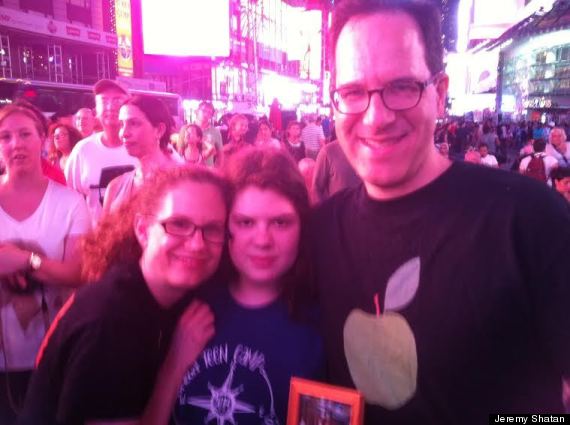

But he and his wife wasted little time in starting the long, slow process of trying to rebuild themselves. They held a memorial for Jacob, attended by Leon Parker, the percussionist to whose music Jacob had taken a liking. Six months before Jacob's death, Hannah was born -- a healthy, happy baby -- and soon after Jacob died they had another son, Noah.

The couple resumed working full-time a few months after Jacob's death as well. For Shatan, however, photography had "lost its flavor."

"You're satisfying yourself by doing creative work, but I also found myself saying, 'What does it mean? Why did I go through this with Jacob? What is the point?'" he said. "You think these big thoughts."

In 2000, he was thrown what he called an unexpected lifeline after he and Capucilli began volunteering for the nonprofit Children's Brain Tumor Foundation. Shatan, who had never done more than attend a bake sale, found himself organizing fundraisers, eventually bringing in thousands of dollars through comedy nights and other events. When his main contact at the foundation sent an email saying she was giving her two weeks' notice, Shatan turned to his wife and said, "I can do that job" -- despite the fact that he had virtually no related experience.

Shatan was offered the role, a mix of public relations and development that was a world removed from his photography career. Not only was the field entirely foreign to him, but it was also the first time Shatan, a longtime freelancer, had felt professionally beholden to a specific entity.

"It was the school of hard knocks, but it was just the right thing for me," he said. "At that point, I was pretty much sold on the nonprofit field. I wanted to help children with cancer."

For four years, Shatan worked for the foundation helping raise money and draw attention to its efforts. Then, in 2005, he took a position with the Columbia University Medical Center, helping run Hope and Heroes, a nonprofit that provides funding to the center's division of pediatric hematology, oncology and stem cell transplantation. Shatan wanted to work in a hospital setting in order to honor the experience his own family had with Jacob's medical team (which was not at Columbia). Shatan never forgot that the surgeons, oncologists and nurses who treated Jacob became some of the most important people in his son's brief life.

Above all, the career change has helped give Shatan's life a sense of meaning he was searching for in the days, weeks and months after Jacob's death -- a renewed sense of purpose he is not sure he would have discovered otherwise.

"When it comes right down to it, it feels like I'm working for him -- for Jacob," said Shatan, who has been employed by Columbia since 2005 and is now the senior director of development at Hope and Heroes.

Early on, Shatan thought constantly about Jacob while at work. Now, after more than a decade working for childhood cancer nonprofits, he is less apt to connect every single spreadsheet that crosses his desk, or every dollar he and his colleagues raise, directly with the memory of his son.

But Jacob is never far from his thoughts.

"The thing about Jacob that we always say is that he was a whole person. He wasn't a baby. I mean, he was a toddler when he died, but we just felt like it was all there, his personality. It just never had the chance to fully express itself," Shatan said.

"Even though I can't save Jacob's life at this point, I can help other families so that they won't have to go what we went through," he continued. "Jacob can't be here with us, but other people will be."