An effective way to burnish your legacy as a public servant to is to rebut your critics before you’ve even left office. Eric Holder seems to be trying to do just that: negotiating multi-billion dollar bank settlements at a rapid pace, and promising tough action in interest rate and currency manipulation cases.

This, Holder seems to hope, will counter the standard argument that his inability to bring a single criminal case against an executive in connection to the financial crisis is, most charitably, hard to fathom.

But Holder's legacy of failure goes even deeper than that: What's more bizarre is his additional failure to adequately prosecute ubiquitous, run-of-the-mill mortgage fraud. Holder failed to land a single big charge against a high-level executive, but he also failed to strike back at the many smaller-bore prosecution opportunities the housing crisis left at his feet.

The Justice Department’s own audit of Holder-era mortgage investigations and prosecutions, released in March, is damning. Outwardly, the Justice Department declared mortgage fraud to be important. But, the report found, the department “did not uniformly ensure that mortgage fraud was prioritized at a level commensurate with its public statements.”

Record-keeping on mortgage cases was so poor that the “Department of Justice could not provide readily verifiable data related to its criminal and civil enforcement efforts.” FBI data that the auditors could make sense of showed that mortgage-fraud cases actually fell each year after the crisis. In 2009, the department opened 1,771 cases. In 2010, the number was 1,174. In 2011, it had fallen to 599.

In a speech at New York University in September, Holder said that, in fact, "the Justice Department has also taken aggressive action, nearly doubling the number of mortgage fraud indictments and criminal convictions between 2009 and 2010, then increasing them even further the following year."

FBI data in the audit show that in 2009, there were 555 mortgage fraud convictions, 1,087 in 2010, and 1,118 in 2011. With the context of the number of new cases opened, what these conviction numbers show are cases working their way through the courts. They are not proof of a increasing, or even sustained, focus on mortgage fraud prosecution.

A thousand convictions per year may sound like a lot, but consider the size of the pre-crisis mortgage market and the large role shady mortgage originators played in it. In 2007, Countrywide Financial alone originated $408 billion in mortgages and serviced 9 million individual mortgages worth a total of $1.5 trillion. This is the same company that failed to send the actual mortgages it originated to the people pooling them into securities, an incredible failure to perform their basic responsibilities. $600 billion in pay option adjustable rate mortgages – widely sold to people who couldn't handle them – were issued industrywide from 2005 to 2007.

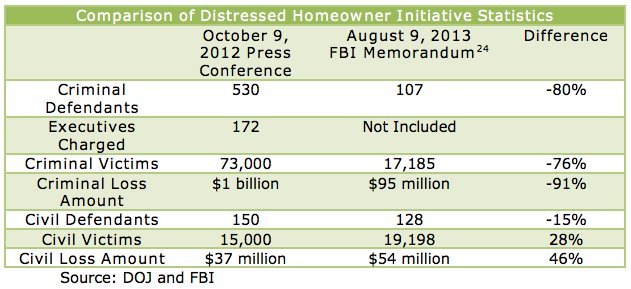

When the Justice Department did release data on its own, it could be glaringly misleading. Big splashy numbers thrown around in press conferences to announce enforcement actions often shrank in reality. Here’s a chart put together by the Justice Department's Inspector General showing the announced results of one enforcement program, compared to what it actually achieved:

Under Holder’s reign, there has been an increase in the number of cases brought against non-U.S. banks for things like money laundering for drug dealers and illegally doing business with Iran. But that’s about pursuing State Department aims, not redressing wrongs that contributed to the financial crisis. They are about bank regulation as a tool to conduct U.S. foreign policy.

Similarly, the cases against big banks for manipulating Libor, a key global interest rate benchmark, do include U.S. banks, but tilt mainly against foreign institutions. And Libor manipulation, like banking Iran, has nothing to do with the mortgage crisis.

When it came to prosecuting the mortgage crisis, Holder missed the big targets, and countless smaller ones as well.

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

It's Another Trump-Biden Showdown — And We Need Your Help

The Future Of Democracy Is At Stake

Our 2024 Coverage Needs You

Your Loyalty Means The World To Us

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

The 2024 election is heating up, and women's rights, health care, voting rights, and the very future of democracy are all at stake. Donald Trump will face Joe Biden in the most consequential vote of our time. And HuffPost will be there, covering every twist and turn. America's future hangs in the balance. Would you consider contributing to support our journalism and keep it free for all during this critical season?

HuffPost believes news should be accessible to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay for it. We rely on readers like you to help fund our work. Any contribution you can make — even as little as $2 — goes directly toward supporting the impactful journalism that we will continue to produce this year. Thank you for being part of our story.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

It's official: Donald Trump will face Joe Biden this fall in the presidential election. As we face the most consequential presidential election of our time, HuffPost is committed to bringing you up-to-date, accurate news about the 2024 race. While other outlets have retreated behind paywalls, you can trust our news will stay free.

But we can't do it without your help. Reader funding is one of the key ways we support our newsroom. Would you consider making a donation to help fund our news during this critical time? Your contributions are vital to supporting a free press.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our journalism free and accessible to all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Can't afford to donate? Support HuffPost by creating a free account and log in while you read.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you'll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.