Tim Burton has lost control of his public persona. It's almost as if he has become one of his own characters. His work has always been a study of the misunderstood, the suburban and the kitsch. Now, he is a misunderstood artist, who grew up in suburbia, spent years being "too dark" and ended up making the kitsch (or, at least, things people mass consume and some critics hate). Somehow the audience that loves Burton pushed him into the realm of critical mass, where he's treated as a cultural object that is either "too Tim Burton" or "not Tim Burton enough." As a Grantland profile of his career asked back around the release of “Dark Shadows:” “How did it all go wrong so fast?”

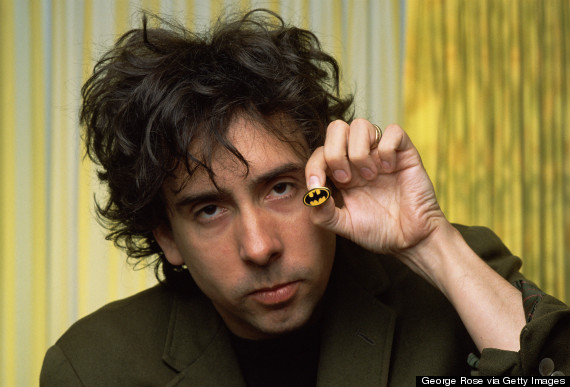

In person, during an interview with HuffPost Entertainment at the Park Hyatt in Manhattan, Burton is scatterbrained in the warmest way possible. He hops up from the couch to say hello, like a claymation figurine moved through stop-motion from sitting to standing with no poses manipulated in between. His Einstein-style hair frizzes out as an apparent extension of his overactive imagination. He has a strong handshake, and he smiles like he means it.

"If you’re lucky enough to have a few successes, then they see you as a ‘thing.’"

Burton is here to talk about “Big Eyes” -- a film that seems like a departure from the Burton canon in terms of scale, as well as relatively low levels of both visual effects and Johnny Depp. But in many ways, "Big Eyes" is thematically in line with his body of work. It tells the story of Margaret Keane, a marginalized artist, struggling to express herself amid twisted psychological abuse waged against her by Walter, her husband. Burton has often tried to ensure the misunderstood became understood. This time the misunderstood are plucked from real life.

Like many of his (fictional) characters before her, there is something of Burton in Keane. “There was a time, not long ago, starting out as an animator, people didn’t even know I could speak. I was very quiet and very non-verbal,” he said, as if mere months and not decades stand between him and that moment. "So, I understand that. That’s how she communicates. She communicated by her painting. ... That’s how I communicated. That’s how I explored my inner life.”

In terms of his recent career, what stands out most about "Big Eyes" is its decidedly low budget. The pure joy in Burton's voice when he talks about the excitement of having to move quickly and be resourceful on set is unbridled. If you weren’t sure he didn’t make “Big Eyes” for the money, you might have heard it in his voice.

Beneath the concept of Burton, there is an artist who is still genuinely and purely excited to make movies and to paint. It’s hard to imagine that person, though. He gets buried under the seemingly repetitive conventions of his own films, the way we define his work by "how Burton" it is, or just the fact that that weird dance at the end of “Alice In Wonderland” continues to exist. All of those ideas about Burton are something of which he is all too self-aware.

“When you start your career it’s more of a surprise. If you’re lucky enough to have a few successes, then they see you as a ‘thing,’ sort of as a commodity,” he said, staring out the window. “I find that a little disturbing, because I always struggled to be a human being.”

What does that mean? To be “a ‘thing’”? It contains so many potential definitions -- to be “a ‘thing’” is to be relevant, to be popular, and then to be so well-received you reach critical mass. Certainly, Burton has reached the ultimate level of “being a thing." Six of Burton's films have grossed more than $100 million in North America, with the aforementioned "Alice in Wonderland" a high water mark. It made $334 million in domestic theaters and more than $1 billion worldwide.

He explains it best. “When you’re a “thing” then there’s this dynamic that gets created. It’s like ‘Oh, it’s just like a Tim Burton movie,’ or, ‘Oh, it’s not like a Tim Burton movie.’ It always sounds negative!” he said. “Maybe I should leave the planet, because I don’t seem to be able to win at anything.”

The reaction to Burton’s work has always been unpredictable. “In some ways it’s quite grounding. That’s why I don’t really read reviews too closely,” he said. “I’ve worked on a lot of films where critics hate it but people love it or critics love it and people hate it!”

That reality truly settled in for Burton after his Museum of Modern Art exhibit. In many ways, that event was the quintessence example of who he is as a cultural object, rejected or accepted as a “thing.” “That MoMa show got so panned. Like completely panned. Worse than Keane!” he said. “At the same time, it had like the highest attendance rate since, like, a Picasso show.”

There lies the other recurring theme we see with “Big Eyes." As in “Ed Wood” before it, Burton has set out to explore what it means to be thought of as “the worst” in your artistic field. On some level, that’s what he’s been dealing with himself, probably since the mid-’90s.

"Critics hate it but people love it or critics love it and people hate it!"

It’s possible to interpret that MoMA quote along the lines of “the critics don’t like me, but who cares as long as the people do!” That’d be fascinating, because it becomes an infinite hall of mirrors: the man obsessed with the kitsch is obsessed with being kitsch. That’s not how he said it, though. He is just as perplexed by these reactions as anyone analyzing them might be.

On top of that, the reception to his work, both critical and public, has changed drastically over time. Many Burton films have become beloved years after their release.

“I learned that very early on with the films. ‘Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure’ and ‘Beetlejuice’ were on, like, the 10 Worst Films Of The Year Awards!” he said. “But then, after time, perceptions change. It’s very interesting because I’ve been through all of that and I go through all of that.”

The other element there is the way perceptions shift with the changing market. Look at his “Batman," created before the superhero franchise metastasized into the defining formula for box office hits. “It was too dark,” he said. “Now, 30 years later, it looks like a light-hearted romp. It’s still kind of in the same zone. So, I’ve been through all that kind of stuff and I go through all that stuff.”

Beyond that is the clear rise of the pop-macabre. Almost in line with “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” “Beetlejuice” and “Edward Scissorhands” was a mounting goth culture (and Hot Topic stores springing up in response). For every kid with a Jack Skellington tattoo was another looking to buy wristbands. There were consumerist trends and social trends far out of Burton’s control that pumped the once-magical elements of his imagination into the omnipresent mass they’ve become.

"I think the whole MoMa experience sort of heightened that dynamic that I feel in this film in terms of public perception."

Though excessively meta, it’s almost too easy to picture Burton directing a film about Burton. There something grotesque about the fact that the audience who devoured his work turned him kitsch and (even more) misunderstood. The dark irony and the torment is all there. Throw in the massive budget and visual effects and you’ve got a film that will be critically eviscerated but likely hit some record at the box office.

All Burton can do is keep being an artist. Somewhere hiding within the 56-year-old is a boy who knows what it’s like to be misunderstood and continues to be really, really excited about the opportunity to finally express himself.

“I think the whole MoMa experience sort of heightened that dynamic that I feel in this film in terms of public perception,” he said, as a Burton-esque smirk crawled across his face. “[But] it got me back into that mode of ‘Let’s make a movie!’”

"Big Eyes" is out in wide release Dec. 25.