Middlebrow is a recap of the week in entertainment, celebrity and television news that provides a comprehensive look at the state of pop culture. From the rock bottom to highfalutin, Middlebrow is your accessible guidebook to the world of entertainment. Sign up to receive it in your inbox here.

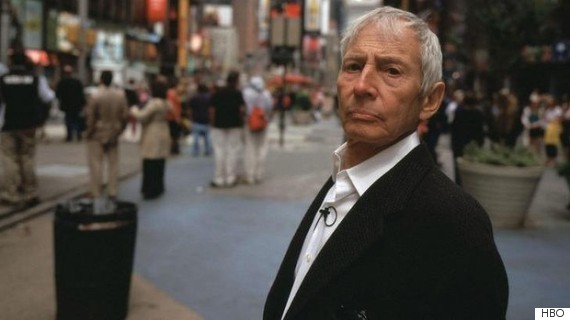

"What did I do? Killed them all, of course," Robert Durst says in the final moments of "The Jinx." His voice -- with a cadence that is an an eerie mix of Heath Ledger's Joker and Woody Allen -- bumps over his hot mic between burps and flushes in the restroom. That chilling last episode of the HBO docu-series aired hours after Durst's arrest for the murder of Susan Berman (one of three alleged Durst murders "The Jinx" depicts). With his subject's arrest, director Andrew Jarecki's years of research came to fruition in real time as the ultimate anxiety-based voyeurism: scandal at just the right distance, combined with the reassurance that the bad guys will get caught.

Sources close to the Los Angeles Police Department told the L.A. Times that "The Jinx" "played a role" in Durst's arrest. And it's not the first time a documentary has had such tangible real-life ramifications. In a follow-up piece, the paper pointed to Errol Morris' "Thin Blue Line," which led to the exoneration of Randall Adams in 1989. In 2011, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky's "Paradise Lost" aided in the release of the three Arkansas men known as the West Memphis Three.

The documentary genre has the potential to impact cases in this way because of its inherent and presumed journalistic ethics. And yet, as entertainment, the form falls under the danger of breaching that code of conduct in the push for sensationalization. When the content is working to convict a suspect rather than free the wrongfully accused, that inherent possibility is much more problematic.

With "The Jinx," Jarecki has ushered the typically pulpy tonality of true crime into the realm of prestige television. True crime has typically fallen into the category of guilty pleasure. (Consider that cop shows like "America's Most Wanted" were the first transition of the documentary into the reality TV.) The HBO mini-series marks a move back to the respectability of the documentary format with true crime content. Its resulting interest and popularity will likely change the future of sub-genre. But what does that shift mean for its subjects?

Problems with "The Jinx" emerged almost as quickly as its rise. Once the news of Durst pulsed into virality, "The Jinx" timeline grew murky. Jarecki failed to answer simple questions about how things proceeded with The New York Times and canceled all future media appearances. Now, it is speculated that Jarecki held on to evidence for several years before handing it over to the police. "The way these events are presented on the show, it looks like Durst’s arrest gave Jarecki leverage in his quest to get more time with his subject," Leon Neyfakh and Jay Deshpande wrote in one potential explanation at Slate. "In reality, it seems like the arrest may have happened more than a year after he conducted his explosive second interview with Durst."

This does not alter Durst's potential guilt. It does call Jarecki's motives into question. As Kate Aurthur wrote at BuzzFeed, "It’s unfortunate that Jarecki’s on-camera statement that its No. 1 goal is to 'get justice' might end up being another of its fictional re-enactments." It's useless to speculate over whether Jarecki deliberately muddled things or why, though it's inarguable that altering the timeline could not align with his priority to "get justice." Really, a film's No. 1 goal can never be to "get justice." A film's No. 1 goal is to entertain. Regardless of good intentions, its impossible for that not to interfere with the ethical obligations inherent in journalism and the justice system.

And where does that leave us? We have a man muttering a possible murder confession to himself while peeing. It might be inadmissible in a court of law, but all that really matters for "The Jinx" is that it's good TV.

Follow Lauren Duca on Twitter: @laurenduca