Have geologists just discovered a new layer of Earth's interior?

A new study suggests that a previously unknown rocky layer may be lurking about 930 miles beneath our feet -- and evidence suggests that it's significantly stiffer than similar layers, which could help explain earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

“The Earth has many layers, like an onion,” study co-author Dr. Lowell Miyagi, an assistant professor of geology and geophysics at the University of Utah, said in a written statement. “Most layers are defined by the minerals that are present. Essentially, we have discovered a new layer in the Earth. This layer isn’t defined by the minerals present, but by the strength of these minerals.”

The pressure is on. For the study, the researchers used a device known as a diamond anvil to simulate how the mineral ferropericlase reacts to high pressure. Ferropericlase is abundant in the Earth's mantle, the layer that's sandwiched between our planet's core and the thin crust on which we live.

(Story continues below image.)

Miyagi holding a press that houses the diamond anvil, in which minerals can be squeezed at pressures akin to those deep within the Earth.

What did the researchers find? The stiffness, or viscosity, of the mineral increased threefold by the time it was subjected to pressure equal to what's found in the lower mantle (930 miles below Earth's surface) compared to the pressure at the boundary of the upper and lower mantle (410 miles beneath the surface). When the researchers mixed ferropericlase with bridgmanite (another mineral found in the lower mantle), the simulation showed that its stiffness at 930 miles was 300 times greater than at 410 miles.

The viscosity increase came as a surprise, since it was previously thought that viscosity varied only slightly at different pressures and temperatures in the planet’s interior.

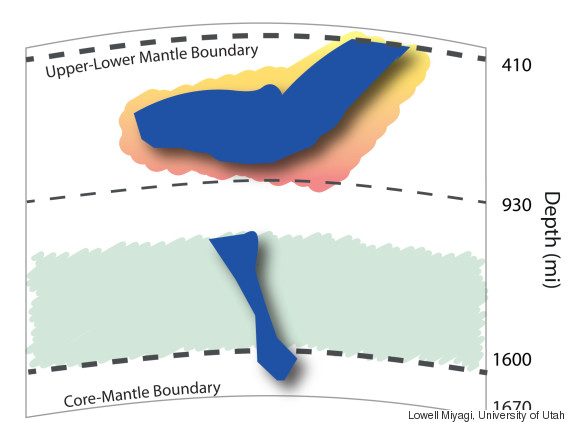

The earthquake connection. The new finding may help explain why many slabs of rock that move and shift beneath Earth's surface stall or temporarily get stuck at around 930 miles underground -- a phenomenon thought to cause earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, The Salt Lake Tribune reported.

“The result was exciting,” Miyagi said in the statement. “In fact, previous seismic images show that many slabs appear to ‘pool’ around 930 miles, including under Indonesia and South America’s Pacific coast. This observation has puzzled seismologists for quite some time, but in the last year, there is new consensus from seismologists that most slabs pool.”

An illustration of a slab of rock sinking through the upper mantle above, through the boundary between the upper and lower mantle at 410 miles depth, then stalling and pooling at a depth of 930 miles.

The finding also suggests that the Earth's interior is hotter than previously believed at that depth below the planet's surface. Miyagi said in the statement that he had calculated that the average temperature at the boundary of the upper and lower mantle is about 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit -- and a scorching 3,900 degrees F at the deeper, more viscous layer.

"If you decrease the ability of the rock in the mantle to mix, it’s also harder for heat to get out of the Earth, which could mean Earth’s interior is hotter than we think," he said.

The study was published online in the journal Nature Geoscience on March 23, 2015.

What else lurks below our feet in Earth's interior? Check out the "Talk Nerdy To Me" video below.