PASADENA HILLS, Mo. -- “Lacee Scott?” the judge called. The 23-year-old rose from a hard black plastic chair, walked past the fireplace and stood before the table at the front of the living room.

From the outside, the house is barely distinguishable from others on the street -- brick, three bedrooms, built in 1948. Over the entrance, however, there is a sign identifying it as City Hall. Once a month, the living room, with its lamps, hardwood floors and clock on the mantle, becomes a courtroom. Those with business before the judge first check in with the clerk in the dining room before taking a seat among the rows of chairs set up in the family room.

Scott, a senior at Alabama A&M University, had lived in Pasadena Hills during high school. Her father, a former St. Louis County police officer, works for Walgreens. Her mother is the principal of a local elementary school. Last summer, when Scott was home visiting her family, a notice was placed on her car.

Parking had never been an issue in her quiet, suburban community. Pasadena Hills is small, with a population of less than 1,000. But the municipality had recently passed an ordinance requiring those parking overnight to display a $10 residential parking sticker on their vehicles. The notice ordered Scott to come to City Hall to obtain the sticker.

The city office has extemely limited business hours, however. The seven-hour drive from Huntsville, Alabama, back to Pasadena Hills also made it difficult for Scott to appear in person. Soon, the city began mailing her threatening letters.

“They sent me a letter and said there would be a warrant out for my arrest if I didn’t come back for this,” Scott told The Huffington Post of her court appearance. “For $10. For parking in front of my house.”

Such experiences are not uncommon in St. Louis County. According to a scathing report from the U.S. Department of Justice released this month, authorities in nearby Ferguson routinely abused the rights of residents, who were viewed "less as constituents to be protected than as potential offenders and sources of revenue." Attorney General Eric Holder said the Ferguson Police Department had essentially served as a “collection agency,” with officers competing to see who could issue the largest number of citations.

A number of Ferguson officials have resigned in the wake of the DOJ report, including the police chief, Thomas Jackson, and the municipal court judge, Ronald Brockmeyer. Yet the problems with municipal courts in St. Louis County extend far beyond Ferguson.

In dozens of interviews with The Huffington Post over the past several months, residents have called the system “out of control,” “inhumane,” "crazy,” “racist,” “unprofessional” and “sickening.” Some have told stories of being slapped with large fines for minor violations and threatened with jail if they couldn’t pay.

“Everyone’s got a horror story about the police," former St. Louis County Police Chief Tim Fitch told HuffPost in a recent interview. "And most of that horror story relates back to being ticketed for some minor violation."

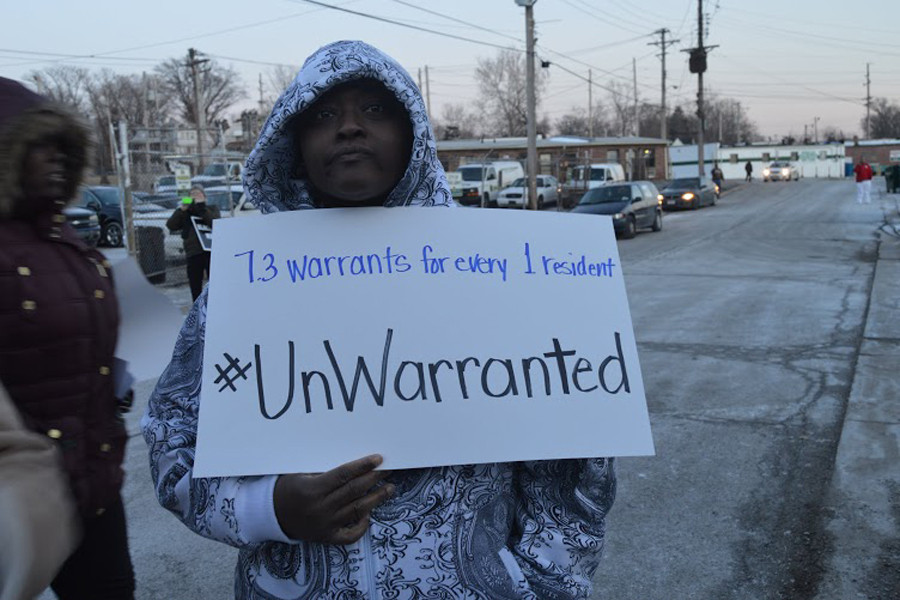

Even before the DOJ released its report, the need to change the way St. Louis County's many tiny municipalities operate had become a rallying cry among protesters, lawmakers and even members of law enforcement.

Last year, Missouri’s attorney general filed suit against several municipalities for violating state law regarding the collection of revenue through traffic fines.

In December, St. Louis Metropolitan Police Chief Sam Dotson said he believed some municipalities “victimize those whom they are designed to protect.” In February, St. Louis County Police Chief Jon Belmar called some of the current practices "immoral."

"If you think that taxation of our citizens through traffic enforcement in St. Louis County is bad, you have no idea how bad it is," Belmar said.

There are 90 separate municipalities in all, home to 11 percent of Missouri's total population. The largest is Florissant, an area of 12 square miles with over 52,000 residents. The smallest, the village of Champ, has just six houses. Population: 13.

Police are an overwhelming presence in St. Louis County. Nationally, the United States has roughly 2.4 police officers for every 1,000 residents, according to FBI statistics. In many parts of St. Louis County, the ratio is much higher. Beverly Hills, Missouri, with fewer than 600 people covering just 13 blocks, has 14 officers on its police force.

As in Ferguson, many of these police departments and local courts generate massive amounts of revenue for city coffers. Municipalities in St. Louis County took in $45 million in fines and fees in 2013 -- 34 percent of the amount collected statewide -- according to Better Together St. Louis, a nonprofit working to improve municipal government in the St. Louis region.

The municipal courts lie at the heart of this system. There are 81 in all. Some are housed in government buildings that were built for public use. Others, like the ones in Pasadena Hills or nearby Country Club Hills, have been set up in buildings designed as residential homes. Kinloch holds court in the cafeteria of an abandoned elementary school. In Beverly Hills, the police department and court share a building with a pharmacy. There’s an ATM in the lobby, and a payday loan outlet is conveniently located next door.

The reach of these courts extends beyond traffic and parking violations. Some municipalities require occupancy permits for those who live in their jurisdictions, which in practice means people can be fined for sleeping over at their boyfriend or girlfriend's house. In some municipalities, overgrown grass or failing to subscribe to a designated trash collection service are offenses that can ultimately lead to an arrest record.

Even clothing choices can be a target. Pine Lawn has a municipal code that bans saggy pants. One man received a $50 fine in 2012 for wearing pants that were too big for his waist, according to court documents. After he missed two court dates associated with his fashion crime, he was slapped with two additional $125 fines, and for a time, there was a warrant out for his arrest.

The ways in which St. Louis County's municipal courts have abused their authority have united a bipartisan coalition of state legislators, activists and law enforcement officials who agree on the need for reform.

Last month, the state Senate passed legislation that would crack down on municipalities that use their courts to generate revenue. That legislation is currently being debated in the state House. The state Supreme Court has also stepped in to help fix the municipal court in Ferguson. Federal civil rights lawsuits have been filed against some municipalities. And the Justice Department has said that municipalities across St. Louis County should take its report on Ferguson as a warning.

“There are many other municipalities in the state of Missouri, and in fact in the country at large, that are engaged in the same kind of practices,” one DOJ official told reporters this month. "They are now on notice."

On payment docket night in Jennings a few months ago, more than one hundred people, almost all of them black, made their way slowly into the courthouse. After passing through the metal detectors, they filled row after row of courtroom seats, waiting their turn to give the city money.

Not long after court officially began, the doors were locked behind them. Those who arrived late were not let inside. Arrest warrants would be issued for the late-comers and those who failed to show for any reason.

First, court officials called for those who could afford to pay more than $75 toward their outstanding fines to step forward. Next, they called for those who could pay more than $50. Then $40. Then $30. Then $25.

If you owe the city money and can afford to pay $100 or more per month, you can skip this whole process and mail in your payment or pay in person any other time during the month. But the poor must sit through this ordeal for hours, the doors opened occasionally only so that smokers can take a cigarette break. Those who can afford the least are forced to stay the longest.

"The time that you're in court is directly related to the amount of money you can pay. So if you can pay more money, you get out faster,” said Thomas Harvey of ArchCity Defenders, a pro bono legal group that has crusaded against the practices of St. Louis County’s network of municipal courts, where they represent poor clients. “You're effectively being punished for being poor.”

Yvonne Fulsom was one of those who had to wait until the bitter end. She had come to the court to make a $25 payment on a $1,000 debt to the city because she let her pitbull urinate in her own yard without a leash. At that rate, she would have to appear in court on the designated night every month for more than three years to pay off the full amount. Miss a night, and she could face arrest.

The threat of incarceration is a brutally effective tool for ensuring that municipal court payments are prioritized in a poor person’s monthly budget. Ferguson was using arrest warrants “almost exclusively for the purpose of compelling payment through the threat of incarceration,” according to the Justice Department report. The practice is common across St. Louis County.

At least the Jennings courtroom is easy to find. That’s not the case in Kinloch, which became one of the first cities incorporated by African-Americans in St. Louis County in the late 19th century. Today, it's a virtual ghost town, home to around 300 residents who mostly live on the edge of the city bordering Ferguson. Phone calls to the number listed for the municipal court online go unanswered, and the address for the court takes you to an abandoned lot.

If you drive around enough amid the burned-down buildings and blocks of abandoned trash, you’ll eventually see a playground full of overgrown weeds and a boarded-up elementary school with a line of people outside. One small sign refers to it as the city hall and the police department.

A University of Missouri–St. Louis student accompanying her boyfriend to court told The Huffington Post that they were “lost and scared” trying to find their way around the nearly abandoned town on a recent court night. Luckily they stumbled upon the right location. Her boyfriend was accused of rolling through a stop sign. An officer banned her and a reporter from the courtroom, in violation of the Missouri constitution. “If your name is not on the docket, you are not allowed in the courtroom," the officer said.

Over in St. Ann, one of the most notorious speed traps in St. Louis County, defendants in municipal court appear before Sean O’Hagan, a prosecutor in the St. Louis Circuit Attorney's Office who serves as a part-time municipal judge. On one night in November, defendant after defendant went before O’Hagan, agreeing to make partial payments or explaining why they couldn’t afford to make good on their outstanding debt.

O'Hagan ordered one defendant with a skullcap on his head to take his “rag” off. He told a woman holding her infant child to find a babysitter for her next court date, despite a warning from a St. Louis County circuit judge last year pointing out that banning children from municipal courts is also a violation of the state constitution.

After one defendant said he didn’t have money to make a payment, O’Hagan told him to “get a job” and noted that retail stores would be hiring seasonal workers “like crazy” for the holidays. He refused a lawyer’s request to allow his client to pay off a fine over two years, saying 18 months was the best he could do. “If it’s not paid, it’s going to be revoked,” he said of the defendant’s drivers license.

Municipal judges are often evaluated by city leaders according to how much revenue they bring in. The DOJ report showed that complaints about how former Ferguson Municipal Court Judge Brockmeyer was doing his job were set aside by the city council and manager. The city, they said, could not “afford to lose any efficiency in our Courts, nor experience any decrease in our Fines and Forfeitures.”

In an interview with HuffPost, O’Hagan denied that his motivation was to bring in money for the city. “I’m not getting into that. That’s not my purview,” he said. “I’m not interested in revenue.”

Today, many municipalities in the northern part of St. Louis County are predominantly black. However, many of them were originally formed in the first half of the 20th century as white enclaves designed to keep blacks out.

After the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the use of racially restrictive covenants in property deeds in 1948, white leaders turned to ostensibly race-neutral means to maintain housing segregation. They passed zoning laws that allowed for only single-family residences and prohibited public housing and apartment complexes. As real-estate developers pushed into new areas, they often formally designated new municipalities.

“We have extremely easy laws of incorporation. We can practically have a couple city blocks and if you have the right paperwork, you can incorporate as a city,” said Robert A. Cohn, the author of The History and Growth of St. Louis County, Missouri.

“If you had six houses and some stationery, you could call yourself a town,” said Colin Gordon, a historian at the University of Iowa who has written about the development of St. Louis area.

Some municipalities pool together to offer certain government services. The Normandy School District, for example, serves students living in 24 different municipalities. But elected leaders in many of the small cities have resisted merging with their neighbors.

The hodgepodge of small municipalities with their very own governments has long caused problems. In 1966, a law professor called Missouri's municipal courts the "misshapen stepchildren of our judicial system" and accused them of overusing arrest warrants.

But the current situation began to take shape after 1980, when an amendment to the state constitution made it more difficult to raise taxes. As property values declined and businesses went under, many of the small cities started looking for other ways to keep themselves afloat.

St. Ann is a community of less than 13,000 people that sits on just over three square miles right near the Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. A decade ago, it was home to Northwest Plaza, then one of the largest shopping malls in the state, which provided a steady stream of sales tax revenue that subsidized the city government. But the mall suffered when new shopping centers were built in the area. The competition, along with repair costs, forced it to close in 2010.

St. Ann officials managed to make up for the mall's absence, at least when it came to the city’s budget. Between 2005 and 2013, the city lost roughly $1.3 million in annual sales tax revenue. In that same time frame, revenue from the city’s municipal court jumped from less than half a million annually to more than $3 million. City budget documents show that court fines and fees have been the single highest source of revenue for St. Ann in recent years.

For Eric Schmitt, a Republican state senator in Missouri whose grandmother lives in St. Ann, the city is a perfect example of what he calls "taxation by citation."

Schmitt is the driving force behind the proposed legislation to crack down on municipalities that use their courts to generate revenue. Current state law puts a 30-percent cap on the amount of a municipality’s budget that can come from traffic enforcement. Schmitt’s bill would lower that cap to 10 percent.

It would also give the law teeth. If some smaller municipalities failed to transfer their overages to the public school district that serves their residents, they would face an automatic ballot initiative asking their residents if the town should be dissolved.

Schmitt has amassed a bipartisan coalition of supporters, including Ferguson activists, the American Civil Liberties Union and local tea party leaders. The chief justice of the Missouri Supreme Court has also expressed support for reforming the municipal courts.

“I’m not sure I’ve worked on an issue where there is such intensity of support from the entire political spectrum, from conservatives to liberals,” said Schmitt. “I think that this is an issue that unites the political spectrum because they see what’s happening and it’s wrong.”

Bill Hennessy, co-founder of the St. Louis Tea Party, said that the situation in Ferguson opened his eyes to the abuses of the municipal courts.

“If a police force seems like its primary mission is to extract fees from poor people in the neighborhood, and a court system has tricks to compound those fees into very large paydays for themselves, if that isn’t an assault on liberty, what is?” he said.

Schmitt's legislation passed the state Senate last month and is currently being debated in the state House. Its chief sponsor there is Republican state Rep. Paul Curtman, who agrees that many St. Louis County municipal courts have become alternative methods of taxation. Both lawmakers represent parts of the greater St. Louis region.

Curtman is also sponsoring a bill that would ban law enforcement agencies from placing ticket quotas on their officers. “People wear the uniform, they carry guns, they get in harm’s way, and if they’re put under pressure to generate revenue for the city rather than to protect and serve, I think that puts them in a very precarious situation,” he said.

Fitch, the former St. Louis County police chief, said that officials commonly lean on their municipal police departments to write tickets and help keep up court revenue, just as the Justice Department documented in Ferguson.

“I’ve never blamed it on police. I’ve always blamed it on the municipal officials who force their police to do that in order to allow them to keep their jobs or get pay raises or whatever they want to use their revenue for,” Fitch said. “You want a raise? Write more tickets. That’s what police officers are being told. It’s from the top down.”

Schmitt agrees. “The law enforcement professionals that I’ve spoken to, they did not go to the police academy to write tickets all day long,” he said.

The bills in the Missouri legislature build on a number of other efforts currently underway to improve the St. Louis County municipal court system. The Ferguson Commission, appointed by Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon (D), has directed a municipal court task force to propose reforms. The Missouri Attorney General’s Office and the State Auditor's Office are looking into violations, and lawsuits filed by private litigants against a handful of municipalities are ongoing. The St. Louis County Municipal Court Improvement Committee, lead by longtime municipal court judge Frank Vatterott, is encouraging the courts to voluntarily implement changes, such as letting defendants choose community service instead of fines and offering legal advisers to help people navigate the system.

Critics say that mere reforms are not enough, however, and that the entire municipal court system needs to be replaced with full-time, professionally operated courts that cannot be so easily pressured by law enforcement and city officials.

Brendan Roediger, a Saint Louis University School of Law professor heavily involved in efforts to reform the courts, worries that minor changes will leave local authorities with far too much power to continue abusive practices.

“There really is local control, at least when it comes to oppressing folks,” he said.

Alec Karakatsanis, a lawyer with Equal Justice Under Law, one of the organizations suing Ferguson and Jennings for essentially running debtors prisons, agreed.

“We don’t just need a few small tinkering reforms to St. Louis municipal courts,” he said.

Despite the acknowledgement from law enforcement and a wide range of political interests that change must come, reform still has many powerful foes in St. Louis County.

The Missouri Municipal League, which advocates for municipalities, has come out strongly in opposition to the House version of Schmitt's legislation. One might reflexively note that the league’s board of directors is overwhelmingly white. But that doesn’t mean the opposition to municipal court reform is equally so.

Ferguson has presented a battle along racial lines, pitting an overwhelmingly white police force and city leadership against a majority black population. In many other municipalities in St. Louis County, however, the officials are black, too. It’s those black officials who are the face of the movement to fight reform.

In December, a group of mainly black mayors from 21 municipalities characterized the state attorney general's lawsuit and other criticism of municipal courts as an “attack on mostly African-American municipalities that are led by African-Americans who were elected by the voting public.” Many of them lined up to testify in opposition to the Schmitt-backed legislation.

"It's not a money grab when you post in your city 'Don't Speed,'” said Viola Murphy, mayor of Cool Valley, a city of just over 1,000 people that obtains nearly 30 percent of its revenue from fines and fees. She further testified that sometimes people “have to be held accountable” for what they do.

Monica Huddleston, mayor of tiny Greendale, population under 700, told lawmakers that she resented how municipal officials were being portrayed as “kings and queens of some fiefdom.” Her focus, she said, was on public safety.

“It’s about enforcing the law, because we deserve for our resident to be protected,” Huddleston said.

Many cities with black leaders will be heavily impacted by efforts to limit municipal court revenue. Without the ability to subsidize their budgets through aggressive ticketing, some may even need to dissolve.

Anthony Gray is an example of how complicated the fight for reform in St. Louis County has become. Gray is a familiar face to Ferguson protesters and news consumers around the world, having served as a lawyer for the family of Michael Brown after the teen’s death. He appeared frequently on television to discuss the shooting. He called for Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot Brown, to be indicted. And he criticized the way St. Louis County’s prosecuting attorney handled the grand jury process.

But in Pine Lawn, which brings in more revenue from fines and fees per capita than any other municipality in St. Louis County, Gray has played a much different role. About a decade ago, he became the municipal court judge. Then he became the prosecuting attorney for about seven years. In 2013, he took the job of police chief. Recently he returned to the role of prosecutor.

Gray and other lawyers working with the Brown family touted the findings of the Justice Department report on Ferguson after it was released. But at the press conference this month, they sidestepped the question of the report's implications for other municipalities in the county.

“This press conference is not about the city of Pine Lawn,” said attorney Daryl Parks.

Still, the fallout from the DOJ report has been swift, and reformers believe it's only a matter of time before more changes are made, however piecemeal they may be. The Missouri Supreme Court transferred an appellate judge to take over hearings on municipal violations in Ferguson for the foreseeable future. Municipalities engaged in the same types of practices may be driven to re-examine their operations before state officials, civil rights attorneys or the federal government steps in.

And the voices of those who have suffered under the current structure, marginalized for so long, are now front and center.