For all the potential dangers of football, ice hockey also has worrisome concussion rates, particularly for women players. And according to a new study by Virginia Tech's influential helmet-testing department, the helmets that hockey players strap on before they hit the ice leave much to be desired when it comes to player safety.

Virginia Tech researchers on Monday released the findings of a three-year look into the ability of 32 popular hockey helmets to protect against concussions -- the school's first investigation of hockey helmets. To put it mildly, the results are worrisome.

4 stars, or “very good”: 0

3 stars, or “good”: 1

2 stars, or “adequate”: 6

1 star, or “marginal”: 16

The researchers, who used a five-star system to grade the helmets, found none safe enough to receive four or five stars, and only one worthy of three stars. Six received two stars, 16 received one star and nine received no stars. (Researchers suggest no one use a helmet that receives zero stars.)

By comparison, football helmets appear significantly safer. Twenty of the 26 football helmets most recently tested by the same Virginia Tech department received ratings of four or five stars, according to ESPN.

Of course, football helmet manufacturers had a head start. Virginia Tech released its first football helmet rankings in 2011, and helmet manufacturers have responded with significant improvements since then.

But even four years ago, football helmets fared better in the rankings than hockey helmets do today, with six of them receiving four or five stars.

Researchers explainscience behind their new hockey helmet rankings.

Stefan Duma, head of Virginia Tech’s Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics, told The Huffington Post over the phone that the hockey helmets’ poor showing compared with football helmets didn’t surprise him.

The sport of football, Duma said, has generally made greater efforts than hockey in recent years to improve helmets’ ability to protect against concussion-inducing hits. But if the tests are any indication, it’s time for hockey to start catching up.

“We expect companies to manufacture [hockey] helmets that can perform better,” Duma said. “And that’s going to mean they’re going to have to be a little larger.”

The research, led by Duma, assistant professor Steven Rowson and doctoral student Bethany Rowson, was published in the Annals of Biomedical Engineering. The Virginia Tech team, which spent more than three years and $500,000 on the rankings, did not accept money from helmet manufacturers.

“We don’t really care what helmet comes out well,” Duma said. “We’re very independent. Our goal is to just help the manufacturers make better helmets.”

To assess the safety of each helmet, researchers created a test that simulates the number and magnitude of hits registered on a typical hockey player.

From a Virginia Tech press release:

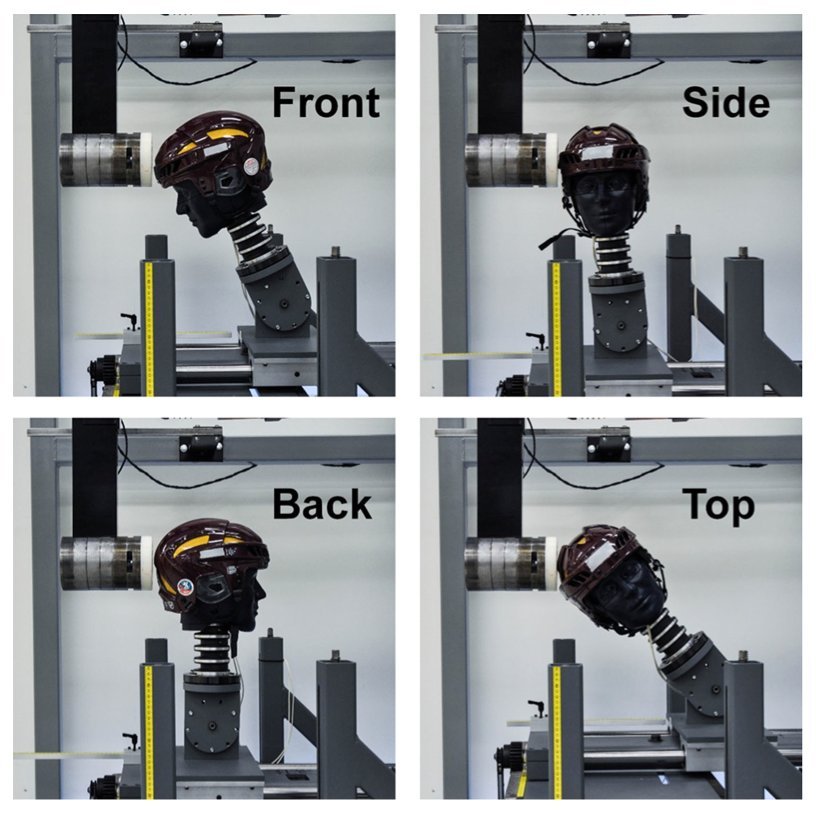

Researchers tested each helmet in four directions at three energy levels twice -- a total 48 tests per model. The entire evaluation process included more than 2,000 impact tests done both on an ice rink and inside a laboratory.

A laboratory dedicated to testing hockey helmets.

The price of a hockey helmet “had no impact” on its ability to fight off concussive hits, according to the release. The “Warrior Krown 360,” which costs $79.98, was the most effective of the 32 helmets surveyed, including some costing many times more. As ESPN notes, the two priciest helmets garnered one star each.

The complete rankings can be found on the Virginia Tech’s Department of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics site.

The Virginia Tech safety rankings have faced some criticism since their release altered the football world four years ago. While they remain highly influential, some critics have questioned whether the tests oversimplify the complicated world of concussion science.

All of the helmets tested for the study had previously been deemed safe by the Hockey Equipment Certification Council. The organization president, Dr. Alan Ashare, told “Outside the Lines” that the results of the study concerned him.

The researchers emphasized in a press release accompanying the study that no helmet is perfect, and the risks associated with any one player depend on a variety of factors, including injury history and genetic predisposition. Nevertheless, they said they hope helmet manufacturers realize there is significant room for improvement.

“Our focus is to improve the safety of the sport,” Duma said in a release. “Our hope is to see new helmets come into the market with improved performance.”