WASHINGTON -- Around 6:30 p.m. on Wednesday, 150 or so people gathered in an otherwise empty National Press Club in downtown D.C.

Hours earlier, in the room down the hall, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) had drawn throngs of press during an appearance before the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. Now, none remained. Instead, attendees still in their work attire sat around tables sipping wine and eating moderately moist chicken dinners, waiting to hear from the guest of the night, a doctor from the Boston Children's Hospital whom few in D.C. -- outside those walls -- knew of.

Dr. Frederick Alt, a 66-year-old Harvard professor of genetics, is responsible for some of the most consequential breakthroughs in cancer research. Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.), the keynote speaker who preceded Alt onstage, described him as a "luminary in the constellation of cancer fighters."

That night, Alt was receiving the Szent-Györgyi Prize from the National Foundation for Cancer Research for a twofold breakthrough. Decades ago, Alt upended conventional wisdom of human genome behavior when he discovered that cancer cells had the capacity to genetically amplify themselves, allowing them to spread, become more dangerous and resist treatments. From there, he discovered how chromosomes recognize the "machinery" that keeps their genomes stable -- a machinery that cancer cells lack. That led to a better understanding of how to protect DNA from the sort of critical damage caused by many cancers. It was research that another speaker called "foundational."

Now on the downward arc of his four-decade career, Alt could have been excused if, on Wednesday, he enjoyed a glass or two of wine and took his award in stride: the compliments of an organization whose mission aligns with his research. But the undertone of the evening's affair was more political, and more dour, than that.

Alt isn't just invested in understanding the genetics of cancer. He's preoccupied by the idea that the next generation of American scientists might not be there to take the baton he's passing.

"I think now is the worst I have ever seen it," he told The Huffington Post of the funding climate, hours before the award ceremony. "The biggest worry is that science as we’ve known it for the past many decades, where we are the leaders -- it is going to disappear if this keeps going.”

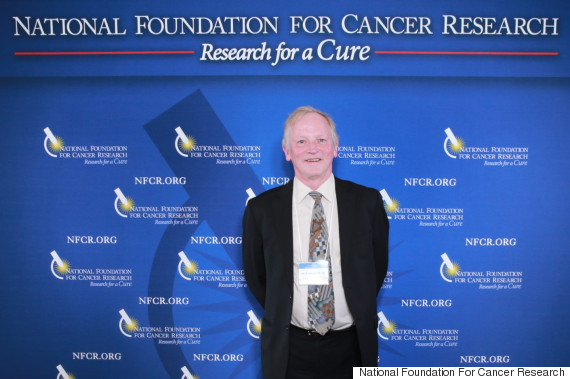

Dr. Alt received the Szent-Györgyi Prize from the National Foundation for Cancer Research Wednesday night.

Funding for the National Institutes of Health, the main federal spigot for biomedical research like Alt's, has bipartisan support among lawmakers. In recent weeks, a number of high-profile conservatives have called for investments in the NIH to be dramatically increased, and for Congress not to fret about cutting spending elsewhere to pay for it. But most people expect that when appropriators fund the government this fall, biomedical research will remain under-addressed.

This, advocates say, would prove catastrophic. Already, the NIH's spending capacity has dropped more than 20 percent over the past decade as the budget lines have failed to keep up with inflation or been reduced by policies like sequestration. The success rates for applicants has sunk into the teens, and the average age of first-time grant recipients has risen to 43 years old. Had the landscape been this bad when he was first pursuing his studies, Alt said, the possibility of his breakthroughs would have been dramatically diminished.

“It wouldn’t have changed my goal of doing [cancer research] because I think when most of us went into it, we were just excited about doing it," he said. "I think where it would have changed the trajectory is there probably would have been a much lower chance of being able to jump into it and succeeding, and probably along the way, you would be out of it."

Alt entered the field of science for reasons unrelated to its financial stability. Before he turned 11, his father had died of prostate cancer and his mother of breast cancer. Alt, then a young kid from Appalachia, decided to understand and, if possible, conquer the disease that took them. Though his parents hadn't made it through elementary school, Alt found his way to Brandeis and, from there, to Stanford University's Department of Biological Sciences. He got his Ph.D. in 1977 studying the drug resistance of cancer cells. Along the way, he pinpointed the role played by genomic instability, providing a road map for developing new therapies.

“And a lot of people followed the road map and expanded it," Alt said. "There were tons of neuroblastoma and medulloblastoma and brain cancer patients that were treated because they had amplified genes, and people found that and they could go in and do [those treatments].”

The first NIH grant Alt received was in 1982. He's had that grant continuously ever since, often with several others supplementing it at the same time. All in all, he estimates that he's received between $20 million and $30 million in funding from the federal government during his career -- a large figure, certainly, but one likely dwarfed by the amount of medical savings his breakthroughs have made possible.

Alt counts himself among the fortunate. He's had a second funding source outside the government: a $1 million-a-year-grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He also entered the field at a time of less competition, and was able to ride the wave of political support that came in the mid-'90s, when President Bill Clinton undertook a doubling of the NIH budget.

Today, he says, there are far fewer opportunities in the field, and the onset of brain drain is both evident and alarming. He himself spends far more time applying for grant money than ever before.

"It is an incredibly discouraging time for a couple of reasons," said Alt. "Americans just don’t see a future at this point in time in science, and it has happened pretty quickly. And the other thing that is real interesting is, I’ve always had a number of Chinese recruits in the lab, and they would end up getting good jobs at MIT and Stanford -- great places. Now, everybody who comes to my lab... they are going now to get their own labs back in China, because they feel there is a much better situation to get funding.”

Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) speaks before the National Foundation for Cancer Research on Wednesday.

As a preamble to a night meant to reward scientific achievement, these comments were decidedly somber. And even amid the celebration Wednesday evening, there were notes of disquiet. As Markey spoke, he praised the dramatic advances that have been made in the field of cancer research -- advances that seemed implausible not too far back. Then he told a story from five years ago, when he and his wife attended a Nobel Prize dinner at the Swedish embassy the night before the winners flew off to Sweden to get their rewards. The room, Markey remembered, was intimate and small -- just six tables in total -- which gave attendees a chance to question the guests.

"How will we compete against the Indians and the Chinese for Nobel Prizes 30 or 40 years from now?" someone asked.

"The answer from one of the Nobel laureates was, we are up here now because of an investment made in us 30, 40 years ago. But we do not yet know the wisdom of this generation," said Markey. "That's our challenge."