One is crafted to make you think and feel; the other’s designed to make you laugh. But two seemingly opposed types of art -- poetry and comics -- have more in common than you’d expect. Both, after all, are meant to transport you to a world beyond your own experiences.

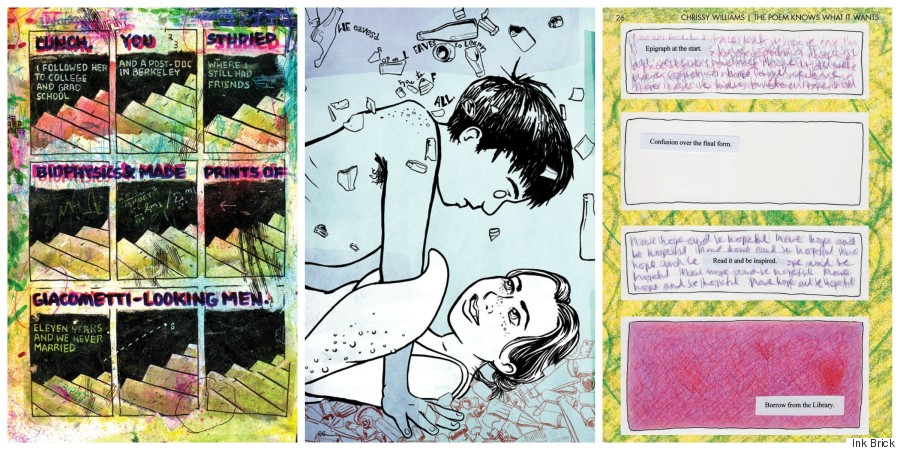

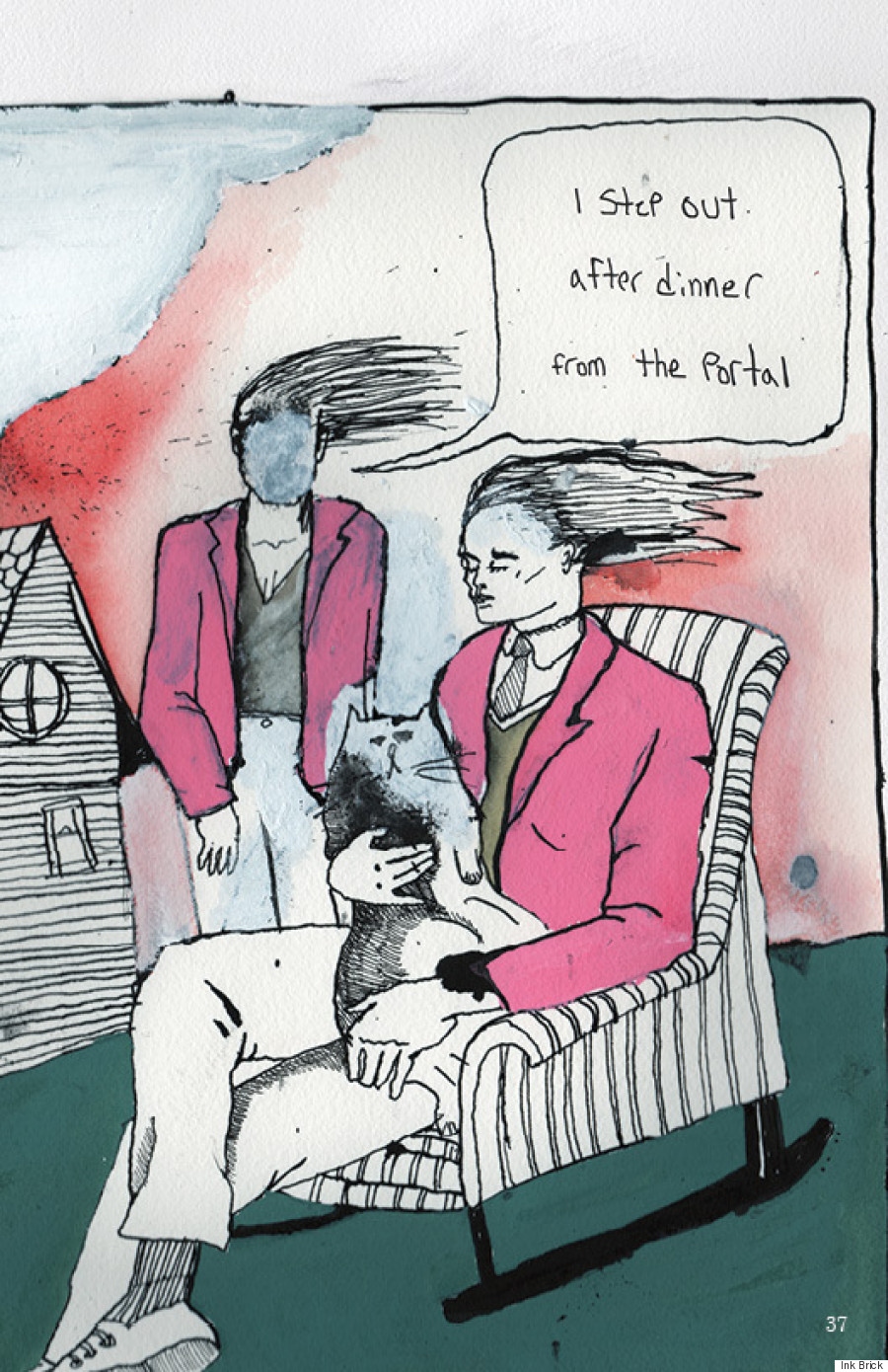

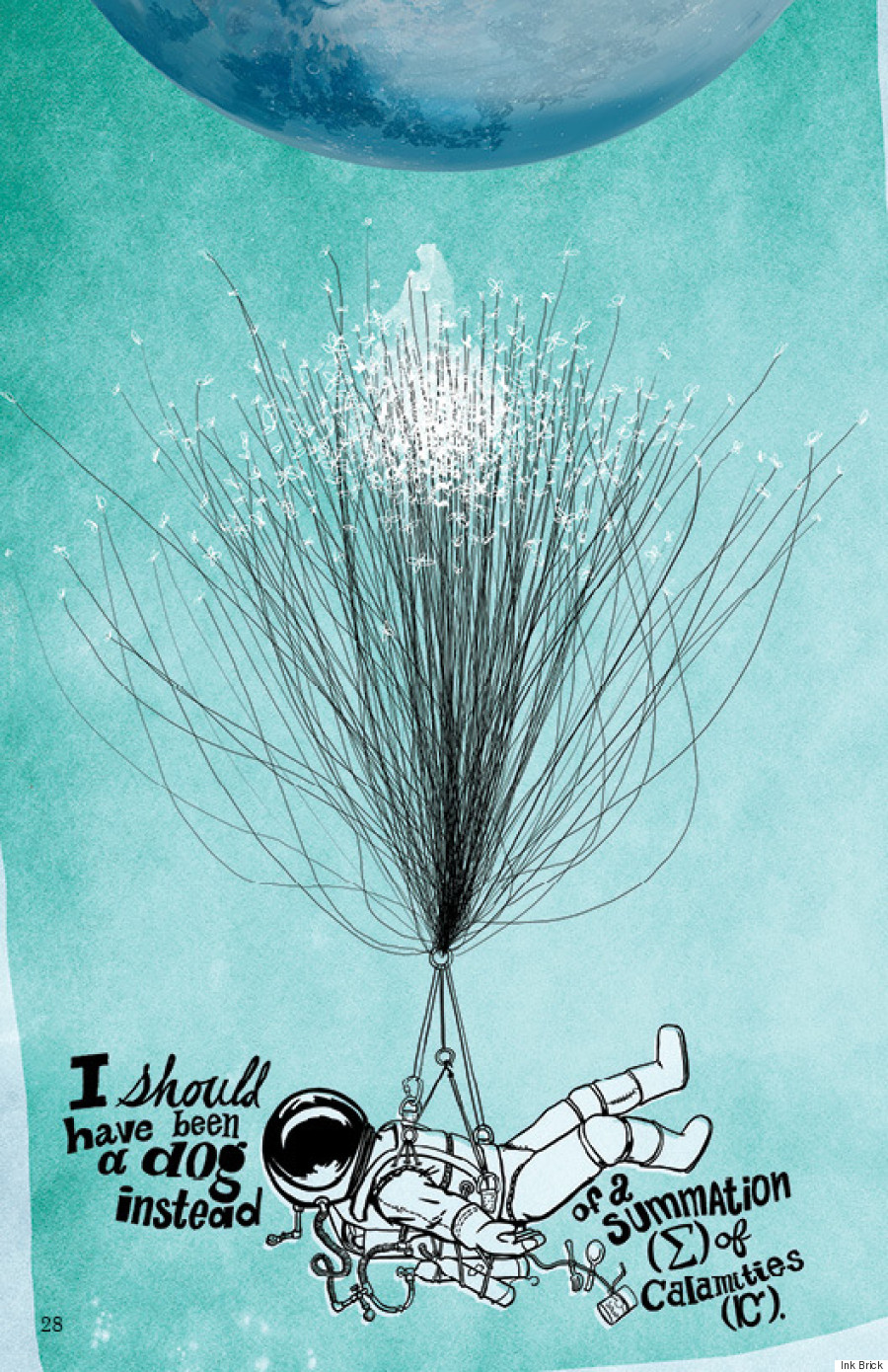

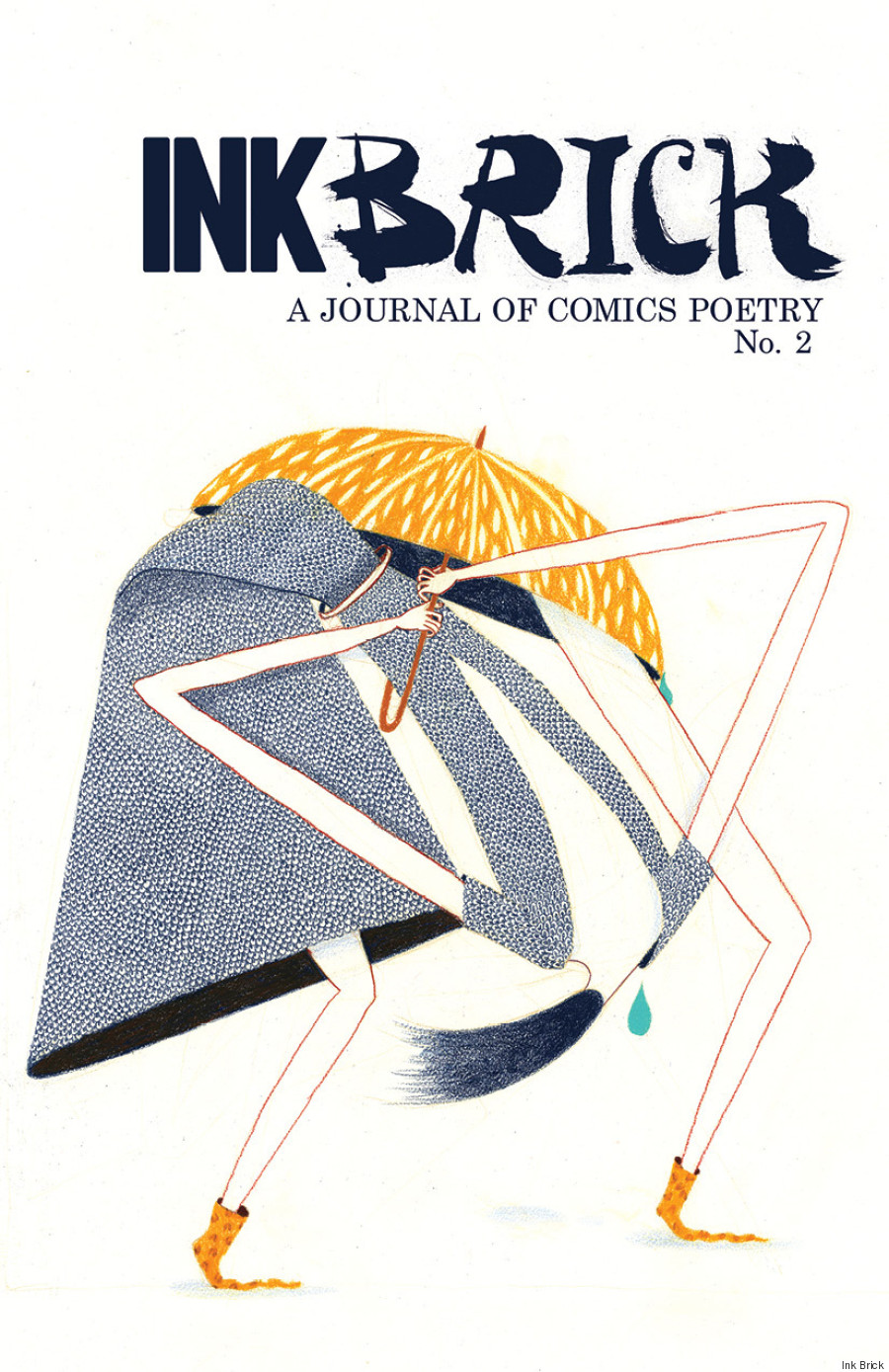

Examining these two crafts by fusing them into one, Ink Brick is a journal that publishes what its editors call comic poetry. Among their published pieces are sketchy, twee love scenes, richly illustrated tales of lost astronauts, and spare panels starring a quiet night sky. We spoke with the editors of Ink Brick about comic poetry, and how their journal counters the notion that verse is elitist.

“The world of MFA programs, teaching appointments, and gatekeeper journals and presses has had its uses, like providing poets with actual career paths,” the editors, Alexander Rothman, Paul K. Tunis, and Alexey Sokolin, wrote in an e-mail. “But it does seem out of touch with the current zeitgeist, which tends toward leveling hierarchies, sharing and remixing material, and blurring the line between creator and audience.”

What is comic poetry?This question is surprisingly hard to answer, not least because “poetry” and “comics” are both container categories for such varied work. But basically, we see comics as writing that uses images to do some or all of the work that other forms would do with language. And poetry is a form that mines language for all it’s worth -- that asks, “What else can language do?” It’s no secret that comics have great power to tell stories, but we’re asking, what else can their visual language do?

We don’t want to be overly prescriptive, but we’re most interested in work that performs a sort of dance between words and images, where each part contributes something different, but both are necessary for the work’s success.

Why did you decide to begin a journal of comic poetry, and what do you hope to accomplish with the journal?Comics poetry has actually been around for quite a while -- dating at least back to the mid-60s, when Joe Brainard and New York School poets like John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, and Barbara Guest collaborated on a brief anthology series called C: Comics. Fifty years later, most people are still unfamiliar with the form, but the last decade or so has seen a groundswell of talented creators working in it. We founded our journal to be a gathering place for that community of creators. We have the journal to showcase what’s possible in the form, and we also publish occasional standalone pieces and distribute books by friends of the press.

Our goals are to introduce readers to the form, help contextualize it by gathering it together, create the space for an artistic conversation, and to help support and celebrate the cartoonist-poets who inspire us. The bit about context is especially important since we know most people are encountering comics poetry for the first time. It’s the kind of work that you need to take your time with, and if it’s doing its job, it will teach you how to read it. Seeing how multiple creators approach the task gives a first-time reader more to work with.

What differentiates comic poetry from, say, text art, or a graphic novel?There’s a lot of carryover between this form and “art comics,” “indie comics,” or “abstract comics” on the one hand and various kinds of visual poetry on the other. And that’s something we want to encourage. We’re interested in categorizing this stuff only insofar as that’s generative of new work, and we really don’t want to keep anyone out of the clubhouse. Also, at some level these terms all break down into silliness. The name “graphic novel,” for instance, was arguably coined in a desperate bid for cultural legitimacy; if work was called something other than “comics,” maybe critics would take it seriously. That fight is over yet “graphic novels” remain, even though plenty of books called that are actually memoirs, biographies, or something else entirely.

As for how we make editorial decisions about what to let into the journal, there are a few things at play. Some of it is of course our individual tastes, and we just “know it when we see it.” Mostly we want to see work that masters, bends, breaks, or just generally plays with the grammar of comics. We like submissions that deconstruct the form -- not necessarily to destabilize it, but to build something new, to put the elements of the comics page into different kinds of conversation with each other.

One might also say that text art and other kinds of visual poetry are focused on the visual elements of language, while we’re focused on the language-like elements of visuals.

Poetry is inherently a visual form, but also inherently involves sound. Can comic poems be read out loud, or would that disrupt the form?This is really tricky. Some examples of the form will naturally lend themselves to being read out loud, while for others it’s going to be hopeless. Readings do exist, usually accompanied by slideshows. Some of these break pages up into individual panels or tiers to better control pace, or incorporate PowerPoint-style transitions or other kinds of animation. Some blend into theater, incorporating sound effects or voice acting.

In general, comics tend to read much more quickly than other forms of writing. Cartoonist-poets often face the challenge of trying to slow readers down while still keeping them engaged. So problems of combining static images and sound apply outside of readings, too.

Ultimately there are as many answers to this question as there are creators. Paul recently had a piece in Drunken Boat that features audio of him reading the words from his piece while another speaker simultaneously describes the visuals. Alexey is wary that reading this work interrupts its gestalt, but sees potential lessons in multimedia pieces that combine audio and film. Alexander’s favorite poet is Gerard Manley Hopkins, a master of sounds, and he really wants to find a way to read his work out loud that feels satisfying.

At least the lack of a clear solution is a blessing as well as a curse. It means that the only way forward is more experimentation and play.

What, in your opinion, is necessary to make a work of comic poetry successful?One of the great things about working in a largely unexplored form is that we know we don’t have the whole answer to this. Someone’s going to figure out a successful way to break any rule we come up with, and that’s exciting. But successful pieces do tend to have some things in common. We have a strong preference for work that balances its freight -- that is, work that doesn’t merely illustrate a preexisting poem, but has the words and images do separate work. Or perhaps the words and images change each other through their juxtaposition. Successful comics poetry will be greater than the sum of its parts.

You should be able to look at this work and find satisfactory answers to questions like, “Why is the cartoonist-poet using this palette? Why did they draw using this particular style of mark making? Why are there this many panels on the page (if there are panels), and why are they laid out like they are?” That doesn’t mean the creator had to consciously think about these things. But good utilization of the form will still address these questions and others like them.

It’s interesting how blank panels could function as line breaks, or even negative capability. Are there other links between poetic conventions and the use of space in comic poetry that might help readers understand the medium?That’s a great question. With the caveat that there aren’t any one-to-one correlations between elements of the comics page and traditional poetic techniques, these are exactly the kinds of connections we’re hoping people will make.

Cartoonists like Frank Santoro and Sophie Yanow have spent a lot of time studying page layout and thinking about what happens when you place images very precisely on a grid. (Yanow composes her pieces on graph paper, for instance.) A cartoonist-poet like John Hankiewicz achieves a powerful sense of rhythm by engaging the grid and placing images at regular intervals. One like Simon Moreton gets richly evocative effects from combining minimalist drawings and empty space.

Thinking of images and space in terms of beats and rests isn’t the only way to approach this work, but it’s one with huge potential, just like traditional poets often draw ideas from music. In a fitting analogy, we’ve noticed an affinity for dance among several cartoonist-poets. (See Hankiewicz again, as well as Keren Katz, who actually is a trained dancer.)

One way to think of this form is in terms of hybridization: splicing comics and poetry. Another way to think of it is translation or even synesthesia. If space can behave like a line or stanza break, what else can it accomplish? What other elements of the comics page might stand in for a rest or pause? What visual elements might correspond to the length or pitch of a note, etc.?

Do you think the form is necessary in keeping poetry alive, in an increasingly visual culture?None of us feel that poetry needs saving, exactly. We find something vital in written poetry, and popular forms like hip hop show that poetry isn’t in any danger of losing relevance.

That said, when many people hear “poetry,” they think of something daunting and maybe even elitist. Whether those associations are entirely fair is debatable, but it seems safe to say they have something to do with poetry tying itself so closely to academia in recent history.

The world of MFA programs, teaching appointments, and gatekeeper journals and presses has had its uses, like providing poets with actual career paths. But it does seem out of touch with the current zeitgeist, which tends toward leveling hierarchies, sharing and remixing material, and blurring the line between creator and audience. Neither model is perfect, but we find the new one exciting.

We do agree that that culture is becoming more visual, and it makes sense for comics to rise in that environment. People are making comics without even knowing it. They use apps like Pic Stitch or feeds on Instagram or Facebook to sequence photos. They converse in emoji. We’re actively reimagining the way we use images to communicate. Any creative work depends on a kind of collaboration or translation between creator and audience, and we want to plug into that energy with Ink Brick.