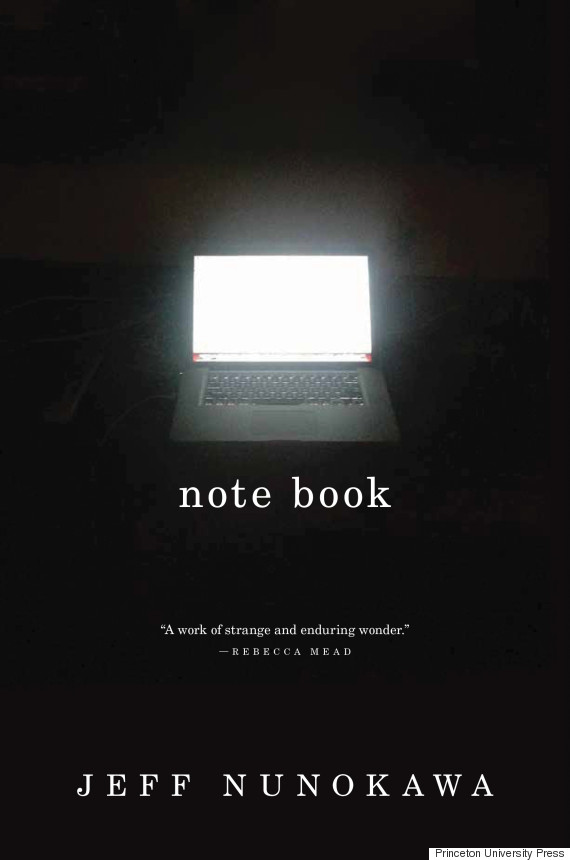

Most interview subjects don’t begin the conversation with an unprompted speech. But when I sat down with Jeff Nunokawa, the author of Note Book, a compilation of brief essays previously published as Facebook notes, he could hardly wait to launch into a full monologue about the book.

Nunokawa’s irrepressible loquaciousness makes sense, if you know him; a long-time English professor at Princeton, he’s notorious around campus for his manic energy, which translates into reading literary criticism while logging hours on the stair stepper at the gym and enthusiastically befriending every student in his orbit. (Full disclosure: I took classes with Nunokawa in college, and we are now friends both on Facebook and in reality.) His students commiserate over the intellectual demands of his up-tempo lectures, which leave note-takers incapacitated with writer’s cramp by the end of the period. Nunokawa has years of practice in the art of verbalizing his thoughts at length.

His profession also brought him to Facebook. His students’ gravitation to the social platform inspired him to bring literature to the space next to photos of last night’s party and cryptic status updates. In 2007, he began posting daily notes to Facebook, mini-essays weaving together literary criticism, personal meditations, and, often, photos of Cristiano Ronaldo and other European soccer stars. This project drew attention from The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead in 2011. He told her, “I used to think of them as prolegomena for a book; now I would see a book as prolegomena for the notes.” Four years later, with thousands of notes under his belt, the book has arrived.

I sat down with Nunokawa to talk about bringing writing from social media to the page, whether the Internet is changing reading for the better or for the worse, and the surprising power of uncertainty:

Jeff Nunokawa: If it’s okay I’d like to discuss a little bit of what animates this project and both what inspires it and also what, as it were, defends it or keeps it going.

When I wake up in the morning, I often find that getting from horizontal to vertical, both physically and a little bit figuratively, is the greatest accomplishment of my day. I lie in bed, and I’m often very unhappy. No more unhappy than most people, but no less so, either. And I think to myself -- I get up and I stumble toward my desk -- and I ask myself, what do I got? What can I pull to, or what can I find here, which will help myself and whoever’s out there -- maybe them, too, a little bit -- move from horizontal to vertical? That’s what I do.

I had, have, very intense and involved literary ambitions for this project. They still adhere, those ambitions.

But more and more, what concerns me with these little essays, is, I put it this way: I started out trying to be like Charles Kinbote in Pale Fire, and more and more I’m ending up feeling more attached to a character named the Reverend Paul Osumi. There was a guy, when I was growing up, who had a little piece in the Honolulu newspapers, ["Today's Thought"]. Little inspirational thought. Some sort of sunny-side-up thought for the day. That’s what he produced every single day. And I thought to myself, “Boy, is this guy a banal fool!” I remember thinking to myself at the time, I was like, “Wow, everything in my life is defined by trying to get away from the Rev. Paul Osumi! That’s what my life’s about!” And then as I was going along, my pride mortified. Not in some sort of heavy masochistic way, but in a good way, like, you know what? That Rev. Paul Osumi? Bless him. I want to be like that. I want to be like that guy, who helped a lot of people get from horizontal to vertical. Now, he came at it with his own scripture, but hey, I’ve got my own scriptures too.

Another thing is, I sort of feel like I’ve got nothing to lose. You reach a point in your life where, you know Fitzgerald’s great line, “At last I was a writer only. At last I had become a writer only.” And at this point in my life -- don’t get me wrong, I’m not about to climb into my grave! -- but I don’t have certain kinds of hopes that I had when I was young. I’m glad the young do have those hopes, but I don’t have those hopes anymore for myself. I’m not going to become a movie star, d’you know what I mean? Cristiano Ronaldo’s never going to marry me! He’s probably never going to know I’m alive! It’s just not going to happen. But what I can do is write. And so I’m going to write every day.

But that’s that!

I’ve actually never had an interview subject ... start. [Laughs, heartily.]

Very professorial of you! Well, I’ve obviously read a lot of your notes on Facebook.Yes, you’re an old friend.

Why Facebook in particular?Initially, it was to reach the students. But then as I was going along, I thought to myself, well, Facebook’s become a more general mode or platform. Not just for the students, as it was when it first came out. I’m trying to produce something that can reach a lot of people. I have no illusions. I’m aware that I can’t compete with images. And that’s the real point. I try not to be too sort of like-based or -driven, because I think people have different relations to what I write than “liking” it or not liking it, but I am very aware that I’m kind of coming up against people who are in a hurry, and they have just a little bit of time.

The deal or the offer that I make to anyone who encounters my work, and I think this is kind of clear, is if you give me two minutes -- just two minutes -- I’ll give you everything I have. I’ll give you a lot. Give me just two minutes, and I’ll show you through just this one line of a Wallace Stevens poem or a Hopkins poem or a snippet from Dickens or whatever, or Nabokov, just one line -- I think I can help you make your day. I think I can help you make your day a day.

Have you ever thought about trying Twitter?The crucial thing about Facebook is that it allows for revision. And I revise all the livelong day. Also I try to keep these things as brief as I can, but they have to be as long as they have to be, and I don’t want the character limit. I try to make my remarks brief, my notes brief, my little prose poems brief, my little sermonettes brief, but I’m a professor after all!

You were talking about the brevity of the notes. But the content is more in the tradition of critical essays, which would typically take a longer form. Do you think the succinctness encouraged by the Facebook note is good for the essay form? Do you think more essayists should be moving toward that sort of expression?Well, let’s put it this way: I don’t think it’s bad for the essay form. What I think is this: I think it’s one of those kind of “my father’s house has many mansions” kind of things. I think what’s good for the essay form is heterogeneity. A lot of arguments about technology are “pro or con? good or bad? advancing or regressing? 'O tempora! O mores!' or 'brave new world'?” I never understood those arguments. I never understood … why not both? Why not both?

A lot of people are worried that social media is a distraction, and even reading on the screen, that e-reading prevents us from thinking about things deeply and critically, and that it encourages a really superficial engagement with material. Is that something that you’re at all concerned about?I’m concerned about that all the time. I think even people’s eyes are so brightened by the screen, become so attached to the brightness of the screen, that people can’t even fix their eyes on the, shall we say, dimmer prospect of a concrete text. I’m a Victorianist. It concerns me a great deal that students find -- and it isn’t their fault, it’s a change in the culture -- find long novels, simply the length of a text, an ordeal.

With the [Facebook] notes, it has to be dwelling in some kind of relation to these texts, these thoughts, these intellectual thoughts wandering through eternity, as Milton says. You have to imagine some kind of ways of thinking about these things in relation to each other, instead of just constantly saying “O tempora! O mores! Oh terrible terrible terrible, it’s the new crack!” You can’t be Luddites, on the other hand you can’t be Panglossians. It’s a world, you have to be engaged with it, in a way that’s beyond just harm reduction.

I often really enjoy when your notes start getting questions in the comments and you get to pursue those strands of thought more. You also, of course, make frequent revisions, and you note that in the comments as well. But those don’t appear in the book. Why was that decision made?It was just very difficult to imagine how to reproduce those without prohibitive permission pursuits. But that’s just a technical answer, and… I want to make a global observation about the problem of moving from the Internet to the book, and then what benefit comes from that. What I write on the Internet, that dwells almost next to viva voce -- almost next to the living voice.

And some part of me thinks well, okay, this book is going to be different from that. It’s going to have certain advantages -- an advantage of concreteness, an opportunity for people if they like to kind of see a bunch of them together rather than serially -- and there are going to be losses, there are going to be casualties, there are going to be failures to transmit, when you move from the Internet to a book, and some part of me just thinks, it’s good to kind of be honest and embrace what is lost. That’s what getting older means.

But you always had in mind making a book out of these?No, not at first. It’s become a much more important thing to me in recent years. I’m older now. I’m much more aware of things passing, of life passing. I want to, like everybody, offer something up that will live after I’m gone. I don’t mean to sound sententious or morbid, I think just that’s the kind of everyday Hegelianism which inspires and burdens us all, right? Everyone wants to leave something for the future. As they say, that’s just mainstream Hegelianism, right? So yeah, that.

Have you ever stopped writing notes every day?I only stop when I’m sick. So, yeah, I write them every single day, every single morning. But they change. It’s funny, ever since my father passed away, a lot of them have had to do with my father.

Do you know who Norman Maclean is? He’s a hero of mine. He was a professor of Renaissance literature at the University of Chicago from Montana. Then he retired, and his kids started encouraging him to start writing down these stories that he would tell them about life in Montana. And he then produced a little book called A River Runs Through It. I’m 56 now, and when I start feeling down about myself, and we all do -- sometimes I think, what have I done? I’m making an asshole of myself with these notes! And I think to myself, hell, Norman Maclean, if I understand my chronology correctly, didn’t start his work until after he retired in his seventies. I still got a shot for something authentic that’ll reach a lot of people.

His last book, which was assembled posthumously ... Maclean talked about this one smokejumper, who hadn’t died in the [Mann Gulch] fire, and he said to his wife, “You do your thing and you’ll do mine, and we’ll do fine,” and she said to Maclean, “I loved my husband very much, but I didn’t know him very well.” And I think there’s a way writing these things where you have to feel that every morning. So much of we do when we speak or write, as professors or students, or probably journalists, is to write with a sense that we know what we’re talking about. It’s important. But sometimes it’s important also to write with a recognition that we don’t know what we’re talking about. That’s what happens as you get older too.

That you realize that you don’t know what you’re talking about?Yeah, or that you realize that it’s important to admit that even when you speak and write. There’s gotta be someplace where there’s people talking, and at the same time they’re trying to figure something out, also they’re admitting that there’s ways they never can.

I feel women often struggle in the opposite direction. There’s a learned tendency to say “I feel like,” and then express a belief. There’s a lot of hedging women do in order to demonstrate that they’re not certain, and so I think that we’re often now training ourselves to not do that in order to seem more assertive and more masculine.I think that skepticism can be a strong move. “I’m not sure what I think about this but I’m pretty sure that I’m not sure.” In other words, there can be a good tension or contradiction between the way something is put and, here’s my strong move here: I don’t know. Not “I’m weak because I don’t know,” but, “I don’t know.” You can show weakness in one area, and still be strong in the ways that matter.

I was really struck by one of your notes called “So true” about how truth has the most force when it’s new or surprising, when it’s overturning something. It’s Coleridge: “Truths ... are too often considered as so true … ” And it made me think, is there a value in error existing in the world so that truth can have this power?That’s interesting, so truth can rock the falseness. I suppose so! I think that’s certainly one way to go. I think that’s right. You’ve basically just described a great deal of vigor from John Stuart Mill to Popper, falsifiability, right? Gotcha! That’s false, and here’s why we know it’s false!

But I think there’s something else, and that’s the following: There’s the falsification school, and the other school is the make-it-new school.

I’ll go running and I’ll listen to the same song over and over again -- I’m looking for that one moment, that one time, that one blessed rendition, where I’m actually hearing the song. Where it’s not just so routinized that I can’t hear it. I’m actually hearing that slight tremble of the voice when Sinatra says ‘Why be afraid of it?’ I can actually hear it.

It’s like classic marriage therapy -- "Try something new! To make it new!" merges with Russian formalism -- make it strange. It’s not that it’s a new thing, but that you can make it new.

You’ve talked about wanting to leave something behind. You talked to a friend or a student about … why does it matter if the words remain if the message has gotten through? Does it matter if it then disappears?I suppose the answer to that has to be the hope that it can go through again. Because God knows lots of dead people’s words, white men and others, have done a lot for me, and for you. So maybe there’s something greedy about it. Maybe these words can do it again, long after I’m gone.

Which authors and works inspire your meditations most often?That’s pretty easy probably. I would say not in any order: Montaigne, Francis Bacon, E.B. White, Gerard Manley Hopkins, James Merrill, Wallace Stevens, George Eliot, Nabokov, Eleanor Roosevelt. Lots of Robert Frost. Frost, more and more. Milton, constantly. Frost has become such an important figure to me, I can’t even bear to think about it sometimes. He’s become such a kind of friend, Frost has. My mother -- very important figure for me. Sometimes people like Walter Pater, in different ways, for different reasons. Samuel Johnson, lots of Johnson. Hume, in different ways. These are a few of my favorite things!

Does your mom read your notes?There is a firewall. She has access to them, but we never speak of them. It’s not clear to me if she does. I know she reads the remarks of hers that I quote, and I’m glad that she does, because I think it makes her feel appreciated, and I want her to feel appreciated, and I think she should feel appreciated, because she says remarkable things. They’re not for her, not directly, but in some ultimate sense. She and my father, to an extent that I think I wasn’t able to acknowledge until he passed, they made me.