Underlying the question of whether European leaders and the Greek state will be able to come to terms amid the financial crisis is one even more fundamental: Is there room in Europe for democracy?

In January, Greek voters elected a government on a platform of anti-austerity, one that argued further cuts would not just be cruel to a people already experiencing 25 percent unemployment, but economically backward as well. European leaders have spent the five months since then doing everything they can to drive that Greek government from power.

Europe's modern experiment with democracy began with many fits and starts, but in recent years it seemed to cement itself. That appears to have been a mirage.

If the troika of economic policy-setters succeeds in ousting the Greek government, it will send a clear message to other European Union countries: You are free to hold elections, but the government you elect can only do what we say.

By forcing Greece to accept their terms or leave the euro, leaders of wealthy eurozone nations want to prevent European democracies from stopping their austerity agenda, analysts say. In this interpretation, European leaders are intent on creating a political crisis that will drive Greece’s left-wing government from power, thus making it known from Spain to Ireland that resistance is futile.

Europe’s desire for a change of government in Greece has become especially apparent in recent days. European Parliament president Martin Schulz told the German newspaper Handelsblatt that his confidence in the Greek government had hit “rock bottom” and that the government should resign if the public votes “yes” in Sunday’s referendum on whether to accept the creditors' proposed bailout deal. Schulz suggested Greece’s creditors could negotiate the final details of a bailout deal with a provisional unelected technocratic Greek government in the interim period before new elections.

An anonymous senior German conservative took it one step further, saying many German lawmakers would not agree to a new bailout deal until the current, left-populist government leaves power. Among members of the conservative Christian Democratic Union, “there would be a lot of colleagues who would vote ‘no’ if [Greek finance minister Yanis] Varoufakis and [Greek prime minister Alexis] Tsipras are asking. For sure. Because there is simply no trust any more. They say, I am not going to give taxpayers’ money to Greece without a reliable partner,” he told the Times of London on Wednesday.

Calling Tsipras and Varoufakis “communists,” the lawmaker said, “We need a reliable partner who wants to do the job,” rather than the Syriza party. Although German chancellor Angela Merkel has left the door open to further negotiations, regardless of which Greek government is in power, she needs the votes of her conservative colleagues to get a bailout deal through the German parliament -- a task that was never going to be easy.

Schulz and the anonymous German parliamentarian claim they reached their conclusions only after losing faith in Syriza. But many analysts argue, with evidence to support their claims, that these latest statements were only making explicit what the creditors’ strategy has been all along: to force Greece’s democratically elected government to accept its terms, or find a new government that will. They have done this by applying consistent economic and political pressure on Greece’s government throughout negotiations, tilting the scales against Syriza and in favor of another austerity-laden bailout deal.

Grexit is a threat, not a choice.

First, the very threat of a “Grexit,” or Greek exit from the euro, only exists because the creditors want it to. There is nothing in eurozone rules that says a country that defaults on its debts is no longer entitled to use the euro currency. Instead, the most likely way a Grexit would occur is if the European Central Bank, which has been providing Greece’s banks with liquidity through its Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) program, sets the exit in motion by permanently cutting off its lending to Greek banks. That would force Greece to implement capital controls to prevent banks from running out of money, and then declare a new currency of unknown value -- in lieu of the euro or alongside it -- in order to regenerate liquidity in the country’s economy.

But much like the eurozone’s vague conditions for expelling a country, the ECB does not have concrete guidelines for making emergency lending available. In a November 2014 study commissioned by the European Parliament, Karl Whelan, an economist at University College Dublin and former economist at the Central Bank of Ireland, warned that the “rules for the provisions of credit via ELA” are “not at all clear” and “appear to be completely ad hoc."

Whelan and other economists, like former IMF senior manager Peter Doyle and Mark Weisbrot, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, argue that this has enabled the ECB to turn on and off its lending on behalf of its preferred policy outcomes. For example, they are suspicious of the ECB's February decision -- shortly after Syriza took office -- to discontinue a waiver permitting Greece to use its junk-rated sovereign debt as collateral for loans, thereby increasing its borrowing costs. We have seen the ECB’s politicized standards play out in the past week as the ECB halted ELA transfers until after the July 5 referendum, and Greek authorities shuttered banks and severely limited daily withdrawals.

As a result, these economists describe a vicious cycle in which the ECB, by constantly warning of a Greek default and Grexit, makes it a self-fulfilling prophecy in order to turn up the pressure on the Greek government. The ECB’s warnings of a Grexit prompt panic and bank withdrawals, forcing Greek banks to rely on the ELA for liquidity. Then the ECB makes clear its willingness to cut off liquidity at a key moment, which shows its willingness to allow Greece to run out of money, worsening depositors’ jitters and deepening the country’s dependence on ELA loans.

By making the threat of a Grexit credible in this way, the ECB can choose to follow through with it, or can use it as a cudgel to force new concessions on Greece. Daniela Gabor, an international finance expert at the University of the West of England’s Bristol Business School, argues this approach never been more apparent than in the past week, when the ECB cut off ELA and forced Greece to implement capital controls until negotiations with creditors resume.

Gabor believes the cutoff was timed to scare Greek citizens into voting “yes” in the July 5 referendum on the creditors’ latest bailout proposal.

“It is a strategy of forcing the government to have the referendum with capital controls,” Gabor said. “That is a clear component of this strategy of trying any way to interfere with the political process and create as much panic and fear in the Greek population to vote ‘yes.’”

It “puts the Greek government in a very difficult position,” Gabor explained. “They know that this makes political legitimacy much more complicated.”

OK, but at least Greek citizens will get a vote on the creditors’ bailout deal, right?

Not exactly. Greece’s creditors are refusing to allow the Greek government to define the question being voted on in the referendum. The Greek government is presenting the referendum as a vote on the most recent bailout-for-austerity proposal by the creditors. Prime Minister Tsipras has said that a “no” vote, rather than signaling a desire to exit the currency union, would strengthen Greece’s hand at the negotiating table.

But top eurozone leaders like Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the Dutch finance minister and eurogroup chair, and Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission president, insist a "no" vote will endanger Greece’s membership in the eurozone. Since the eurozone nations, through the ECB, control Greece’s status in the currency union, this amounts to a thinly veiled threat.

That means Greek voters heading to the polls on Sunday must not only consider the merits of the European creditors’ most recent proposal, but also speculate about how the eurozone will interpret their votes. Polls show Greeks oppose austerity and support Syriza, but also back a deal that would keep them in the euro. But if Greeks believe they are being forced to decide between a euro on the creditors’ terms or no euro at all, they may be more likely to choose the former.

What would a deal that honors Greek democracy look like?

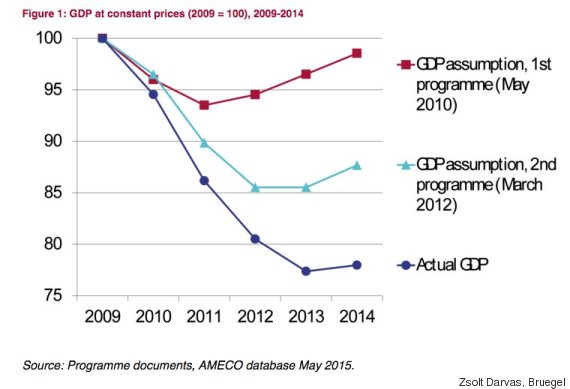

A deal that honors Greek democracy would allow the Syriza-led government to at least partly fulfill the platform on which it was elected: ending austerity policies that are hurting Greece economically, while preserving its place in the eurozone. In practice that means lowering Greece’s primary budget surplus, and in so doing, granting Greece the fiscal flexibility it needs to restore some of the economic activity it has lost over five years of austerity. The Greek economy has shrunk by more than one-quarter since 2008. Economists of many ideologies agree this contraction can largely be blamed on a combination of dramatic spending cuts and tax increases Greece enacted as a condition of bailout funds.

But in order for Greece to have lower annual fiscal targets and remain on a steady debt trajectory, it first needs significant debt relief from its creditors. The IMF’s own chief economist has admitted as much.

And it is virtually undisputed that Greece will never be able to pay back all of its debts in full. (Greece’s total public debt is equal to 177 percent of its GDP.) In fact, NSA-intercepted communication released by Wikileaks on Wednesday shows that German chancellor Angela Merkel admitted in October 2011 that the bailout was saddling Greece with unsustainable levels of debt.

But Greece’s creditors have never once committed to relieving Greece’s debt burden as part of negotiations over unlocking the last tranche of bailout money Greece needs to make its upcoming debt payments. After Tsipras called the referendum vote last Saturday, European Commission president Juncker made a last-minute counter-offer that dangled the prospect of discussions of debt relief in the fall, pending Greece’s completion of another round of austerity-driven reforms. But Greece has reason to distrust creditors’ promises to address debt relief later. In 2012, they promised to consider debt relief if Greece implemented the reforms it was asking for, but never followed through after Greece did as it was told.