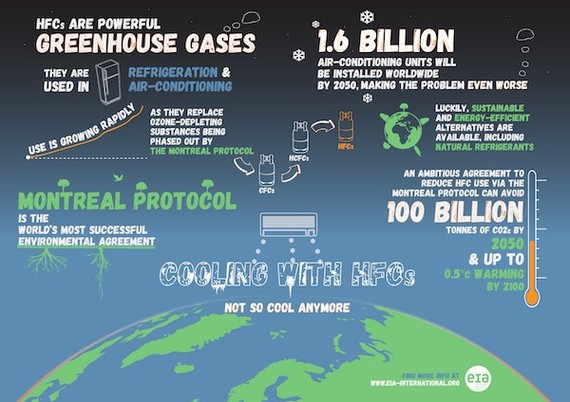

Since its adoption in 1987, the Montreal Protocol has been widely acclaimed as the world's most successful environmental treaty, putting the ozone layer on the path to recovery.

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) - industrial gases once widely used in aerosols, foams, refrigeration and air-conditioning - will be completely phased out by the end of 2016.

But as International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer is marked today, the Montreal Protocol has new challenges ahead of it.

As an unintended consequence, the replacement chemicals for ozone-depleting substances were found to be safe for the ozone layer but very harmful for the climate.

Fortunately, there is a very real prospect of achieving ambitious measures to clamp down on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) at next month's Montreal Protocol meeting in Kigali - the first real test of climate action after 2015's historic Paris agreement.

Montreal Protocol's successful regulatory regime

Back in 1974, Mario Molina and F Sherwood Rowland discovered that the breakdown of CFC molecules in the atmosphere caused ozone layer depletion. Later, in 1985, two British scientists documented the thinning of spring-time levels of ozone above Antarctica, prompting swift international cooperation which led to the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987. Two years later, the international community agreed to phase out CFCs using a regulatory model which controlled both sources of production and consumption to cut CFCs.

'A load of rubbish' proclaimed the chairman of DuPont, the major CFC producer, about Molina and Rowland's research which ultimately gained them the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1995. Eventually, the chemical giant would agree on production controls and endorse Montreal Protocol measures, noting their inevitability - and with an eye on the new, huge profits to be made from patent-protected replacement chemicals hydrocholofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

HCFCs are almost phased out in developed countries and began to be eliminated in developing countries from 2013, leading to the global market adoption of their successor chemicals HFCs and a massive consequent rise in HFC emissions. Some countries have already taken regulatory action to address what has become the fastest growing group of greenhouse gases; for example, the European F-Gas Regulation, the most ambitious legislation of its kind, will reduce HFCs and other fluorinated gases to 21 per cent of 2009-12 levels by 2030.

Developing countries are set to gain from switching to climate-friendlier alternatives or leapfrogging directly to HFC-free technologies with higher energy efficiency. Research shows at least 70 per cent of sectors using HCFCs in countries with high ambient temperatures can skip directly to climate-friendly alternatives with equal or better energy efficiency.

As the world is set to install 1.6 billion air-conditioning units by 2050, with most demand in developing countries, it would make a huge difference for the climate and the electricity grids in hot and highly urbanised regions for these to be both HFC-free and energy efficient; for instance, in Delhi, India, air conditioning accounts for 40-60 per cent of peak electricity demand during summer.

The Montreal Protocol took a first step to regulate HFCs in 2015 with the 'Dubai Pathway on HFCs' which kick-started the formal negotiation towards an HFC phase-down amendment. In Vienna in July this year, Parties made significant progress towards a deal while providing reassurances on the financial support mechanism for developing countries to implement reduction measures. Senior diplomats participated in the meetings to express their strong support to reach an ambitious deal in Kigali.

Synergies in the global climate architecture

The Paris agreement, currently under ratification, was rightly celebrated as a significant climate victory with all countries agreeing to keep warming well below 2°C and, for the first time, to pursue efforts to cap warming at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

However, emissions targets enshrined for implementation by 2030 are alarmingly insufficient to put the brakes on global climate change and are paving the way for a temperature increase between 2.7° and 3.7°C, depending on modelling assumptions. Scientists are clearly sceptical about the prospects to cap warming without relying on controversial mitigation technologies, such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage.

Some estimates caution that at current global emission levels, the 1.5°C carbon budget will be spent in just five years. In terms of emission-reduction strategies, we have a clear option ahead of us - accelerate the pace of climate action using all available mitigation levers to unlock the full potential for reductions from all sectors.

Tapping into the full mitigation potential of short-term climate forcers such as HFCs offers great prospects of achieving significant emission reductions. As HFCs have very high global warming potentials compared to CO2 but significantly shorter atmospheric lifespans, the sooner we curb HFCs the higher the chance to achieve a positive impact on the climate while creating the breathing space needed to concentrate on long-term CO2 mitigation strategies.

The total mitigation from all countries' climate plans under the Paris agreement will equate to a reduction of 9 to 11 billion tonnes of CO2e by 2030. The HFC amendment can avoid up to 100 billion tonnes CO2e by 2050, with an additional 100 billion tonnes from energy efficiency improvements. The Paris agreement remains the major climate instrument to reduce global greenhouse emissions but cannot deliver fast enough by itself.

However, the Montreal Protocol has a huge window of opportunity to slam the brakes on runaway climate change. If ambitious, the HFC phase-down amendment expected in Kigali will provide critical momentum to fast-track climate action and show real political will to implement the Paris agreement.

Back in the 1980s, many sceptics believed it was too late for the ozone layer to recover but the world stood united, took swift action and successfully tackled an enormous challenge.

We now have a limited opportunity to replicate that success - not just for ourselves but for the sake of all life on Earth.