Note: Our accounts contain the personal recollections and opinions of the individual interviewed. The views expressed should not be considered official statements of the U.S. government or the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. ADST conducts oral history interviews with retired U.S. diplomats, and uses their accounts to form narratives around specific events or concepts, in order to further the study of American diplomatic history and provide the historical perspective of those directly involved.

Unrest in the Middle East has been an unrelenting problem for centuries, the Gordian knot that cannot be cut. The Camp David Accords marked the first substantive step toward that end and still stand as a watershed moment. After meeting in secret at Camp David for 13 days of negations, the parties were able to make a breakthrough in the talks. President Jimmy Carter, President Anwar El Sadat of Egypt, and Prime Minister Menachem Begin signed the Camp David Accords on September 17, 1978.

The Accords comprised A Framework for Peace in the Middle East, and A Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel. The first framework was later condemned by the United Nations General Assembly because it regarded Palestinian territories without participation from the Palestinians. The second framework though, led directly to the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty, which is still in effect today, despite considerable upheaval in the region.

The Accords and subsequent events, including Sadat's historic visit to Jerusalem, were very controversial, especially in the Arab world. Yasser Arafat of the PLO, King Hussein of Jordan, and Hafez al-Assad of Syria refused to participate in multilateral peace talks, and many Arabs turned against Sadat because they believed he wasn't defending the Arab objective. Despite criticism back home, Begin and Sadat received world-wide praise for their efforts. As a result of the Camp David Accords, Begin and Sadat were both awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1978.

Ambassadors Samuel W. Lewis and Hermann Frederick Eilts reflect on their experiences during the often heated negotiations, the difficulties in reaching a compromise, the race to get an agreement before the deadline, and the trouble with the accords that started coming up almost immediately afterward. Eilts served as Ambassador to Egypt from 1974-79, and Lewis as Ambassador to Israel from 1977-85; both were crucial players in the negotiations. Ambassador Lewis was interviewed by Peter Jessup in 1998; Ambassador Eilts was interviewed by Ambassador William D. Brewer in 1988.

Go here to read the full account. You can read about the assassination of Sadat, the opening of the UN Sinai Field Mission, and other Moments on the Middle East. Invitations to Camp David

LEWIS: In retrospect, it is clear that Begin and Sadat had concluded by this time that the negotiating process between their two governments had come to an end and that a meeting between the two of them hosted by Carter might be the only hope for progress. So they both accepted the invitation with alacrity. There was about a month between the invitation having been delivered and the start of the Camp David conference, on September 5, 1978.

Carter was extremely well briefed; he was really on top of the material and was knowledgeable of all aspects -- having been immersed almost continuously with the problem for eighteen months.

Carter was extremely well briefed; he was really on top of the material and was knowledgeable of all aspects -- having been immersed almost continuously with the problem for eighteen months.

The State [Department] officials were by and large rather pessimistic about what could be achieved at Camp David. Carter had asked State to prepare a set of goals for what might be achieved. I remember that during the lunch, Carter indicated that he thought the goals were far too modest and that he was setting his sights considerably higher. He was aiming for a full peace, not a partial or intermediary solution. I thought at the time that it was very wise for Carter to shoot high, although I also was not as optimistic as the President as what might be realistically expected.

Nerves Run High as Confrontation Looms

EILTS: Both Sam Lewis, our Ambassador to Israel, and I warned the President at that luncheon, "Don't bring Sadat and Begin together, other than for social events." The reason was clear. By that time, Sadat's reaction to Begin, despite their earlier meetings, was very negative and bitter. Carter seemed to accept that. To our surprise, however, no sooner had we gotten to Camp David when Carter called Sadat and Begin together and said to Sadat, "Mr. President why don't you read your proposal?" Sadat hadn't been prepared for this, but he had the Egyptian proposal with him and in a monotone he read that proposal. Begin was chafing at the bit.

At the end of the presentation, Carter said, "Well, let's now adjourn and meet again tomorrow morning." Then Carter came to the American delegation. He looked at Sam Lewis and at me, and said, "You fellows told me not to get them together. It worked beautifully. No problem."

The following morning he got them together again. No sooner were they seated when Begin said, "Mr. President, if you're going to accept this man's (Sadat, he was much more polite) proposal, I insist the Israeli proposal be accepted as the basis for discussion." With that Sadat, pointing to Begin, said, "This man is responsible for all the problems." Sparks were flying and Carter had to adjourn the meeting right away.

From that point on the negotiations took place between the American delegation and the Israelis; and the American delegation and the Egyptians. There was no direct negotiating between Egyptians and Israelis. Sadat and Begin didn't meet again except in a social context.

A Difference in Strategy Between Sadat and Begin

LEWIS: Sadat had adopted what I considered a brilliant strategy in dealing with Carter; that strategy culminated at Camp David. Sadat was uninterested in details; he was interested only in the broad principles. Begin was very interested in the details and every language change was significant to Begin. Begin's staff was very eager for an agreement and their strategy throughout was designed to bring Begin around to something that was acceptable to others and viable from the Israeli point of view. Therefore, the strategy of the two delegations were almost mirror images.

EILTS: The first ten days -- first of all it took much more than a week -- by the end of the tenth day we still had no agreement on anything. Every agreement was tentative, conditional on something else. So it went. Carter was becoming very impatient. He had immobilized himself at Camp David for this long a period. And he finally said to the parties, "I have to go back to Washington on Sunday. Either we get something by Sunday, or it's a failure." By then, of course, his own prestige was heavily invested in this, which was important.

The Jerusalem Crisis and the Danger of Losing the Agreement

LEWIS: During Sunday, we were putting the final touches on the draft. Carter was preparing to launch his campaign with the other two leaders to get them to the signing point. Sunday, in fact, turned into a cliffhanger, not a wind-down as it should have. That I gather is common to many conferences in which you think you have a deal, only to find out at the last minute that there are still issues to be resolved. That is what happened at Camp David on the final day.

LEWIS: During Sunday, we were putting the final touches on the draft. Carter was preparing to launch his campaign with the other two leaders to get them to the signing point. Sunday, in fact, turned into a cliffhanger, not a wind-down as it should have. That I gather is common to many conferences in which you think you have a deal, only to find out at the last minute that there are still issues to be resolved. That is what happened at Camp David on the final day.

We thought everything had been pretty well resolved. Then the all of a sudden, the issue of Jerusalem exploded unexpectedly. Since no meeting of the minds was possible on the issue. it had been agreed by the three delegations that each would state its own view of the problem in a letter to be attached to the agreement.

Actually, we had all agreed on some language at one point -- a simple statement that Jerusalem should remain undivided, the rights to the holy places should be respected and that Jerusalem's ultimate status should be left to further negotiations -- all very vague and general -- but Sadat was persuaded Saturday night by his advisors not to agree to that because it was giving away too much for Arab sensitivities.

The difficulties arose because Carter and Vance thought that it had been clear to Begin that the U.S. would restate our view on Jerusalem -- that our views would be stated in addition to the Israeli and Egyptian views. The fact that we had to state our views is because that was the understanding we had reached with Sadat in exchange for his approval of dropping the whole issue out of the final Camp David agreement. He knew of course, that our view was somewhat closer to his than it was to that of Israel's and he wanted our view on the public record, even if were to be in a side letter.

This was one of the two topics that was discussed in the marathon meeting Saturday night. It is there that the misunderstanding started which is not surprising in light of the weariness of the participants which may have made them miss the nuances. It is a lesson why negotiations should not be carried on too late at night.

So on Sunday morning, Vance read to Dayan the text of our draft letter on Jerusalem, which was essentially a summary of statements that [U.S. Ambassadors to the United Nations] Arthur Goldberg and Charles Yost had made to the UN previously in 1967 and 1969. Dayan was very upset to hear our position restated so baldly -- namely that the status of Jerusalem was subject to later negotiations, which along with other nuances, implied that we viewed Jerusalem as occupied territory and not an integral part of Israel.

Begin was furious when he spoke to his delegation. So I went back and reported to Vance, who insisted that Begin had been told of our intentions the night before and had not objected. Carter had given assurances just that Sunday morning that we would state our position in a side letter. The public restatement of our position on Jerusalem was sine qua non for Sadat's signature to the final agreement.

Carter was polite, but cool and tough. He said he could not go back on his word to Sadat. He had made known his intentions to make the letter public the night before. He tactfully pointed out that it was not the Israeli responsibility to tell the U.S. whether or where or how it should state its views and policies.

The meeting broke up in a pessimistic view. Then Carter picked up a hint from Dayan. He asked Vance to look at the language of our draft letter again to see what could be done to ease Israeli concerns without breaking his commitment to Sadat. In fact, Vance had already realized by then that the original language could not stand and had already commissioned a new draft. It was practically ready when Carter asked for it.

The new draft merely said that our new position was as had been stated by Goldberg and Yost, but didn't restate it. This version was eventually accepted by both Begin and Sadat. So the "Jerusalem crisis" was contained and didn't raise its head again at Camp David.

This episode was a good illustration of the last minute unexpected events that can blow up towards the end of a conference, which can be resolved, but that at the moment looks like a sure tragedy. In retrospect, I think that the Jerusalem issue could have wrecked the conference because on Sunday morning, although the Israelis were so close to achieving peace with Egypt and would not have wished to have it slip away, Begin might have driven Sadat out of the game inadvertently if he had dragged the meeting out further.

Sealing the Deal - Euphoric Israel, Scared Egypt

LEWIS: At approximately 5:30 p.m., that Sunday afternoon, after the deal had been sealed, we were deluged by a cloudburst, which delayed our departure for about an hour. We then took all the documents and got on helicopters to the White House. The Israeli delegation, which I accompanied on their helicopter, was euphoric. Everybody was very happy.

The Egyptians were putting up a good front, but they were essentially very unhappy and scared. Many members of the Egyptian delegation genuinely felt they were committing suicide by being party to this peace agreement.

It was clear that Begin's rather obnoxious and difficult negotiating strategy had paid off. I thought then and I still believe now that Israel got a somewhat better deal than Egypt did, but that both sides had made a good many concessions. It was obvious that neither side was totally satisfied which I consider a good negotiating outcome.

That Sunday evening, we landed at the Washington Monument helipad at about 9:45 p.m. and motorcaded to the White House. The Israelis were all there. Carter, Begin and Sadat sat on the rostrum.

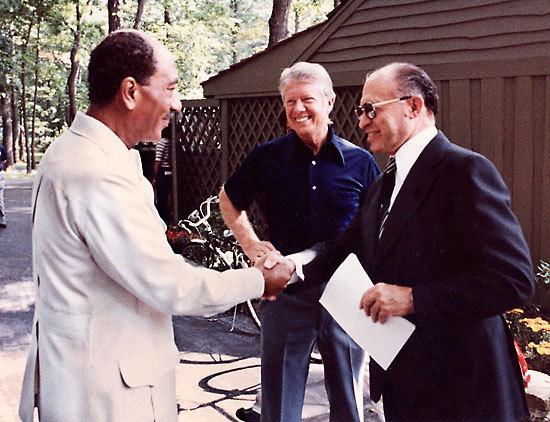

Begin stole the show; he made a warm and witty speech. Sadat gave a formal speech, praising Carter, but not mentioning Begin at all. Then the famous picture was taken; this is the one that got a lot of press play. Begin embraced Carter and then Sadat for a photo opportunity which he was anxious to have on the record. He mouse-trapped Sadat into that picture; Sadat couldn't avoid it. It was a very smooth performance.

Troubles With the Accords and an Opportunity Lost

EILTS: That Sunday night, after the signing ceremony, but after we went to the State Department and sent messages all over the world, including to Arab leaders, explaining the agreement, and indicating we also had agreement, not textually in the accords but as a side agreement, a protracted settlement freeze for the West Bank and Gaza and asking for their support.

EILTS: That Sunday night, after the signing ceremony, but after we went to the State Department and sent messages all over the world, including to Arab leaders, explaining the agreement, and indicating we also had agreement, not textually in the accords but as a side agreement, a protracted settlement freeze for the West Bank and Gaza and asking for their support.

By then, Sadat's Foreign Minister had resigned in protest against the Camp David accords when Carter got the letter from Begin on Monday. It didn't speak of a protracted settlement freeze. Instead, it spoke of a three-month freeze, tied to the time period stipulated in the Sinai agreement for the conclusion of an Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty. This had nothing to do with the West Bank-Gaza. Carter would not go back to Begin, he would not himself call Begin and say, "Look, this is not consistent with your agreement of yesterday." I guess he wasn't sure.

Quite frankly, he rushed through finishing the Camp David accords and perhaps allowed himself to be taken in. And then later, that same Monday, Begin went to New York and made a public statement on what he meant by autonomy for the West Bank. This made it very clear that what he had in mind was totally different from what we had sent out as our explanatory messages to Arab and other leaders. So the Arab states, as you know, generally wouldn't agree.

But Camp David was a modest accomplishment. My problem with Camp David is two-fold: one that we gave away too much. Certainly Carter, in going into the Summit, had much grander ideas of what could come out of it, including doing something for the Palestinians. My second is this: that then we did not, either under Carter and certainly not under Reagan, take what we had obtained in Camp David and try to develop it into something more meaningful. Once we got the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, that was pretty much it. The following West Bank-Gaza autonomy talks languished.

For Carter, of course, he couldn't involve himself. He was in the election campaign. He had the Iranian hostage crisis.

Then came a new Administration with a different sense of priorities. The Reagan administration, it seemed, really didn't care. It had strategic consensus and the Soviets on its mind, things of that sort. So the two problems, in my view, we did not at the end of Camp David work enough to prevent some of the dangers that, at least many of us, saw. And, second, afterward for a variety of reasons, we did not try vigorously to make something out of Camp David.