If we look hard enough, we're likely all the products of refugees. The very founding of America was based on the concept of refuge. It stands to reason -- we should be sympathetic. Last summer the UN High Commission on Refugees released in their annual global trends report that the number of displaced people globally had reached an all-time historic high of nearly 60 million. And since, the crisis has only gotten worse. The UNHCR, the World Food Program and other development agencies are struggling to make ends meet. UNHCR has received less than half of the $4.5 billion required to meet the needs of the more than 4 million Syrians in neighboring countries. Last fall the WFP was forced to drop one-third of the recipients of it's food voucher program as well as scale back its assistance to less than 50 cents per person per day because of budget shortfalls.

To address these shortfalls, WFP recently announced a crowdfunding platform called "Share the Meal" which allows smartphone users from around the world to support the meals of refugee children. While perhaps well-intended, it is the equivalent of trying to boil the ocean with a tea kettle; it is an aspirational gesture that is a far cry from a comprehensive and sensible solution. Although the Kickstarters of the world have had tremendous impact, the most essential needs of those displaced should not rely on the chance generosity of strangers.

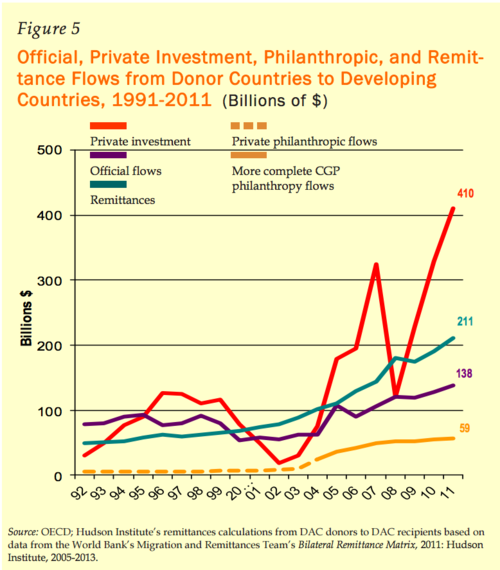

This sort of funding mechanism is a product of uninspired thinking and is a legacy of the development policies of the past several decades that have relied simply on bilateral assistance. Whiled 20 years ago the majority of capital flows to the developing world were in the form of official development assistance (ODA), now private capital flows trump ODA roughly 3:1. See figure:

As the private sector by far and away accounts for the lion's share of capital flows to low and middle income countries, it is particularly well suited to providing a more thorough solution to the funding gaps posed by the refugee crisis. Capital markets, both debt and equity, could be leveraged in ways that are truly innovative to meet the social needs of refugees and communities where they are being resettled.

Public debt markets are perhaps most suited to meet the short term needs of refugee resettlement. Multiple studies have shown that integration of refugees is a net positive for the formal economy. Because of the promise of a future return, the concept of sovereign refugee bonds -- has recently been floated in the public zeitgeist by individuals such as Gary Kleiman. Countries with high refugee burden could issue local and external commercial debt to investors on public markets in the form of sovereign bonds. If the issuing countries have a subprime credit score, such as Jordan or Lebanon (B1 and B2, respectively, from Moody's), the loan could carry a partial or full guarantee by development agencies such as USAID or the World Bank to cover investor risk.

The US government has provided sovereign loan guarantees to five different countries (Israel, Egypt, Tunisia, Jordan and Ukraine) since 1993 to support economic reform initiatives in the target countries. According to Sam Ostrander, a spokesperson from USAID, sovereign guarantees are specifically authorized by Congress and administered by USAID. Once Congress authorizes the use of a sovereign guarantee, an interagency committee meets to structure the guarantee and agree on terms and conditions. USAID considers the program a success -- to date, $21.3 billion in sovereign loan guarantees have been issued and there have been no defaults.

Recently, Sovereign Bond Guarantees have moved beyond simply targeting economic reform initiatives and have been used more broadly to assist countries such as Jordan facing a large influx of refugees. The support of external financing has allowed Jordan to issue the bonds at a more favorable rate (3% compared to 6.6%), thus reducing the public sector deficit. The Jordanian guarantee is perhaps a proven test case for this alternative type of development finance. Despite external shocks, Jordan has maintained single digit inflation, is experiencing steady growth and continues its targeted social protection programs. From an investor standpoint, these types of guaranteed fixed income products at 3-5% yields are ideal compared rates of 2 percent for US treasuries and zero and negative yields in Europe and Japan.

The natural iteration of this would be to link innovative development finance to outcomes. For instance, development agencies or banks could discount the loans if metrics of successful resettlement are met, such as high employment in the formal economy and enrollment of refugee children in school. If certain indicators are met, agencies such as USAID would essentially be providing a concessional loan and underwriting the difference. This type of blended capital, with elements of both aid and traditional finance, is relatively unchartered yet holds promise.

Equity markets could also be leveraged in ways to support the refugee crisis. Imagine a refugee fund comprised of listed companies in the Amman Stock Exchange that all have a role in resettlement. Kleinman suggests that "major index weights come from banking, real estate, cement, power and other firms that would be relevant. Purely private logistics and other businesses as now active in Europe could also be equity targets either individually or in a pooled fund." This type of fund would certainly appeal to impact oriented investors, but may also attract traditional commercial equity investors as well.

In the anonymous millions of refugees is someone's father, daughter, child. The funding gaps are not simply numbers, they represent one's most human needs -- education, housing, healthcare, food. These can't be left to chance or handouts, but rather can be met through the careful and thoughtful leverage of markets.